Andrew Potter: Eddie Van Halen, Bill and Ted, and mourning a generation

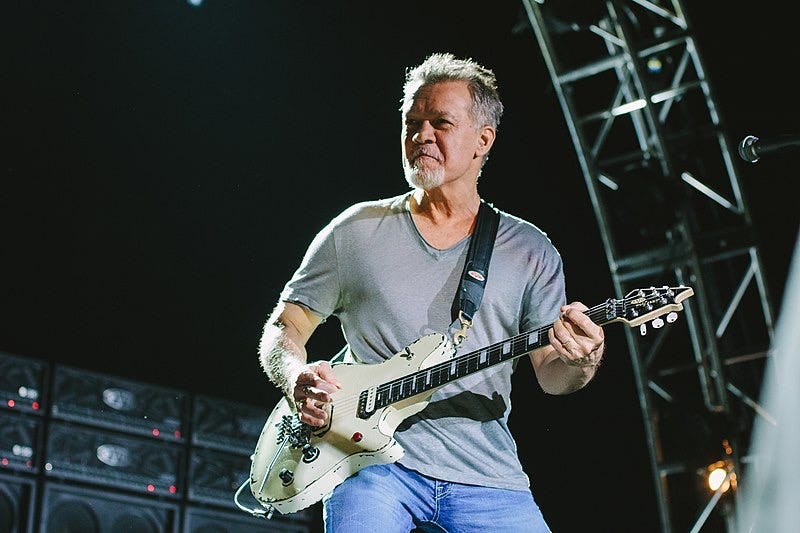

With the passing of the greatest rock guitarist in history, Generation X starts to face the music.

The death of Eddie Van Halen last week didn’t come as a huge surprise. Partly because in 2020, no bad news should surprise anyone, but also, more prosaically, his family and bandmates had been sending signals for almost a year that the guitarist was in bad shape.

It also didn’t resonate with the broader culture like the deaths of David Bowie and Prince did in 2016. Still, it stings, and in some ways it stings more than the loss of Bowie and Prince. A lot of music came out of the 1980s, and a lot of it sucked. But one subgenre that absolutely did not suck was the Los Angeles rock scene that birthed monster bands like Motley Crue, Guns n Roses, Jane’s Addiction, and the Red Hot Chili Peppers. The definitive musical genre of the 1980s was guitar rock, its crucible was The Sunset Strip, and Van Halen was present at the creation.

A lot of Van Halen’s music comes across as juvenile party rock, largely thanks to the band’s frontman David Lee Roth, who was the lyricist as well as the clown prince of rock showmanship. And unlike Roth, Eddie was relatively quiet and unassuming. But he wasn’t given much to false modesty either. He once described his song “Hot for Teacher” as “beyond any boogie I’ve ever heard.” He said he wrote the song “Panama” when someone asked if he could write an AC/DC tune; for those listening at home, note that “Panama” contains at least three complete AC/DC songs before the first chorus.

So whatever the band’s image, no one really doubted that Eddie Van Halen was a musical genius. By the end of the band’s sixth album, the absolutely stupendous 1984, he had said pretty much everything there was to say on rock guitar. He was known more than anything for a trick, the two-handed tapping technique, and one of the great debates that consumed the rock guitar magazines in the early ‘80s was the question of whether Eddie Van Halen had invented tapping. At one point, one of the magazines found a song from the 1970s where the guitarist had put his right index finger on the fretboard to sound a single note during a song, and they even tabbed it out, as if to prove "Eddie didn't invent tapping." When they interviewed Eddie about it his answer was, "Look, I never said 'oh look at me I'm bitchin’, I invented tapping.’ I'm just saying, no one ever showed it to me."

Van Halen didn’t just play guitar rock, it was California guitar rock, at a time when California was about the most aspirational place there could be. Van Halen was the soundtrack to the California moment that ran from Fast Times at Ridgemont High to The Karate Kid to The Lost Boys to Encino Man. It was everything rad and tubular and gnarly. It was partying and boozing and girls and skateboarding and guitars and guys in big hair and spandex and bandanas. And it was loud, crude, sweaty guitar rock.

It’s no coincidence the most important film of that era, Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure, is about two kids from the L.A. suburb of San Dimas trying to start a band and wanting to play guitar like Van Halen. In one of the film’s first scenes, they stumble through an epic Socratic paradox:

The central problem that drives the plot is that Bill and Ted need to write the rock song that will bring harmony to the universe, and in order to do that they need to pass their history exam. So a guy from the future gives them a time machine phone booth so they can travel to the past and learn about history.

It sounds crazy, but the idea that music could save the world was a widely accepted view at the time. It was pretty much the conceit of the Live Aid concert and its sequels. With his Lifehouse project, Pete Townshend of The Who notoriously spent a big chunk of the ‘70s literally trying to write a rock opera that would bring the world into a state of permanent, unified ecstasy. The contribution of the Bill and Ted movie to this idea was to simply take as given that the song that would do this would sound more or less like a Van Halen tune.

Which brings us to this year’s Bill and Ted Face the Music, the third film in the series and the first since the 1991 sequel Bill and Ted’s Bogus Journey.

Bill and Ted are middle-aged dads now, and the intervening decades haven’t gone as expected. Wyld Stallyns had some success, but their big song “Those Who Rock” failed to bring the world together. No one listens to guitar rock anymore, they haven’t had a hit in years, and they are still struggling to write the one song. Ted’s dad still thinks they are losers, and their wives are dragging them to couples therapy. Only their daughters, Billie and Thea, seem to think their music is cool.

In the bulk of the movie, Bill and Ted spend most of it traveling ever further into the future, trying to meet their future selves after they’ve written the song that will save the universe, so they can bring it back to the present. Meanwhile, their daughters are busy traveling back in time gathering a group of musicians to serve as the greatest backing band in history.

It’s mostly goofy, innocent stuff, but there are two key scenes. In one, Bill and Ted meet their elderly versions lying side by side in bed in a nursing home. They each take a moment to apologize to their future selves for letting them down. And elderly Bill and Ted pat them on the head and forgive them. Later, Bill and Ted end up in Hell where they run into their estranged former bandmate, Death. They make up with him, and he’s back in the band.

The whole thing ends more or less as you’d expect, with Bill and Ted playing a song that saves the world. Except it’s not a Van Halen-inspired Wyld Stallyns tune, not even close. Instead, the song is written by their daughters, and it is a global kumbaya sing-along to some god awful electronica-fuelled Arcade Fire sort of number.

We talk a lot about generations and what defines them — Boomers and Xers and Millennials and Zs — but ultimately a generation is just a scene. It is about who and what you claim as your own, but this is something that is determined largely in retrospect. You only know what was yours once something comes along that is clearly alien and you realize that the culture was something you shared, that you made for one another. Eventually the whole scene moves on.

That’s why one of the weirdest things about getting older is realizing just how much of what you took for granted as part of the permanent furniture of the world was actually highly transient: The Iron Curtain. Guitar rock. Your own hopes and dreams and ambitions. Sometimes they all come wrapped together like a package deal, and failing at one makes it seem like you’ve failed at it all.

So to make the explicit more explicit: In a movie called Bill and Ted Face the Music, the two failed Gen X heroes literally make their peace with themselves, and then with Death.

And that’s the big moral here. A generation isn’t just about who you claim, it is who you mourn. Eddie Van Halen was 65 when he died, which technically makes him a fully paid up Baby Boomer. But so what. Guitar rock was ours, which is why right now Generation X is mourning the passing of the greatest rock guitarist in history.

Rest in Peace, Eddie Van Halen. You were totally bitchin’.

Top image credit: Abby Gillardi

The Line is Canada’s last, best hope for irreverent commentary. We reject bullshit. We love lively writing. Please consider supporting us by subscribing. Follow us on Twitter @the_lineca. Fight with us on Facebook. Pitch us something: lineeditor@protonmail.com

"That’s why one of the weirdest things about getting older is realizing just how much of what you took for granted as part of the permanent furniture of the world was actually highly transient: The Iron Curtain. Guitar rock. Your own hopes and dreams and ambitions." - I love this. Love it.