Andrew Potter: Our constitutional time bomb has finally gone off

Sooner or later Charter values were going to run straight up against provincial identity-building efforts; someone using the notwithstanding clause was inevitable.

By: Andrew Potter

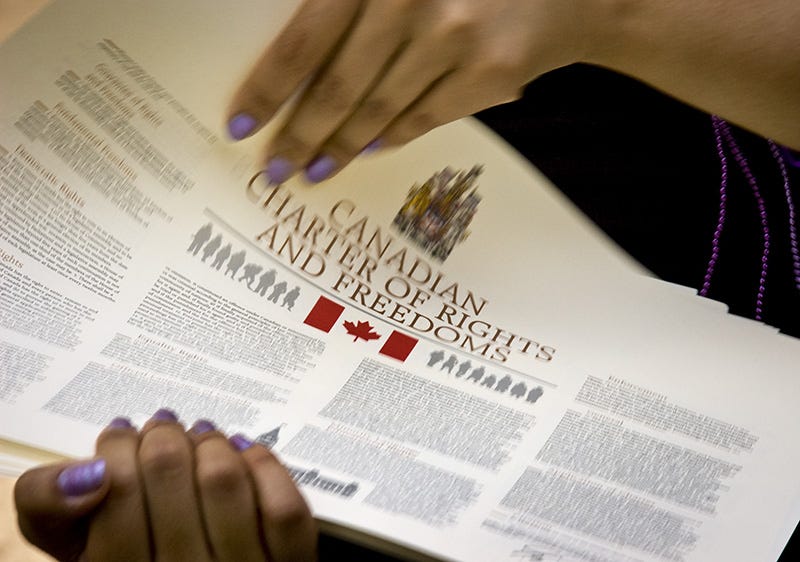

In 1982, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and the provincial premiers inserted a time bomb into the Canadian constitution. It finally went off last week, when an elementary school teacher in West Quebec was removed from the classroom for wearing a hijab, in violation of Bill 21, the province’s secularism law.

The case has generated no shortage of outraged commentary in Canada and abroad, with many denouncing what they see as the “bigotry” of the Quebec law. In The Line on Tuesday, Ken Boessenkool and Jamie Carroll argued that far from implementing a secular state, Quebec has simply imposed a state religion that takes precedence over private belief. In response to these criticisms, many Quebecers say that this is just another round of Quebec bashing. The rest of Canada needs to recognize that the province is different, and to mind its own business.

But it is important to realize that something like this was going to happen sooner or later. The patriation of the constitution and the adoption of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982 seriously destabilized the Canadian constitutional order, and the twin efforts of the Meech Lake and Charlottetown accords to fix that instability only made things worse. But the real ticking bomb here is s.33 of the Charter, a.k.a. the notwithstanding clause, which allows legislatures to override certain sections of the Charter for renewable five-year terms.

The basic tension is between two more or less incompatible views of the country. On the one hand there is the original concept of a federal Canada, where citizens’ political identities are shaped by and through their relationship with their provincial, and to a lesser extent, national, governments. On the other hand, the Charter created a newer understanding of Canadians as individual rights bearers with political and social identities prior to the state, underwritten by the Charter itself.

As the late Alan Cairns noted in Charter versus Federalism, his extraordinarily prescient little book from 1990, what is so destabilizing here is that there are now essentially two parts to the constitution, each of which speaks to a different conception of what it means to be a Canadian. The amending formula adopted in 1982 privileges our federal and legislative identities, while the Charter foregrounds our status as individual rights bearers, with the courts as the ultimate guardians of those rights.

Reconciling the more communitarian and parliamentary tendency of the older federalist perspective with the newer individualist and judicialized promises of the Charter was always going to be a difficult enough task. Unfortunately, the Supreme Court has consistently confused the issue by aggressively promoting Charter values on social issues (e.g. R v Morgentaler, Reference re Same-Sex Marriage) while being preposterously deferential to the provincialist view when it comes to regulatory and economic issues (e.g. R v. Comeau).

But overall, the Charter has done what Pierre Trudeau intended. For the first time, it provided an institutional mechanism through which Canadians could identify with one another as Canadians, and outside of their relationship to their legislatures. When Justin Trudeau told a town hall in Winnipeg in 2015 that “a Canadian is a Canadian is a Canadian,” he was mostly just trying to score points against the Harper government’s decision to revoke the citizenship of a convicted terrorist. But the phrase resonated because a lot of people actually believe it. There’s a reason why the Charter routinely tops the list of symbols and institutions that are seen as binding the country together.

This rankles the provinces of course, and nowhere does it rankle more than in Quebec, by making federal institutions, and in particular the Supreme Court, the locus of citizenship. Sooner or later Charter values were going to run straight up against provincial identity-building efforts, and the eventual use of the notwithstanding clause was an inevitability. So while Quebec’s commentariat has been wondering what business it is of the ROC when the province uses it and for what ends, what is notable about the notwithstanding clause is that it allows a legislature to override precisely those parts of the Charter that have been most effective at inculcating a pan-Canadian identity. For the most part, Canadians are upset because they see the victims of Bill 21 not as put-upon Quebecers with whom they have little in common, but as fellow Canadians.

What, if anything, should be done about all of this? The Serious People tell us that Ottawa has to stay out of it, that there are no votes to be gained in making a stink about Bill 21, and it might only make things worse by reviving separatist sentiment in Quebec. Aside from the usual political cynicism at work here, there’s something deeply fishy about an argument that suggests that the only way to keep Quebec in Canada is to treat Quebecers as if they aren’t Canadians.

That said, making this entirely about Quebec is not helpful. The notwithstanding clause was put in the Charter at the insistence of many of the provinces, especially Alberta, and it isn’t going anywhere. But what federal politicians need to stop doing is making their views on the clause and its use contingent on the narrow political calculations of the day. And the best way to do this would be for Ottawa to declare its flat, unequivocal, and all-encompassing opposition to s.33.

Parliament could begin by adopting a blanket policy against the use of the notwithstanding clause at the federal level. Start with a motion in the Commons, and pass whatever laws, resolutions or executive orders you can. Simultaneously, the federal government should commit to opposing the use of the clause always and everywhere, no matter the province, no matter the government, no matter the reason. It should promise to fund whatever opposition it can, intervening at whatever level it might.

A lot of this will be merely symbolic, but that’s largely the point. All nations are imagined communities, Canada more than most, and the Charter of Rights and Freedoms is the most successful and effective nation-building document in Canada’s history. The bomb that was put in it can’t be defused, but the federal government should commit to making it clear to all Canadians who is responsible for setting it off, while doing what it can do clean up the damage.

The Line is Canada’s last, best hope for irreverent commentary. We reject bullshit. We love lively writing. Please consider supporting us by subscribing. Follow us on Twitter @the_lineca. Fight with us on Facebook. Pitch us something: lineeditor@protonmail.com

I’m going to take a slightly different point of view: Canada has always been defined by two realities, French speakers in Quebec and those of us who complain about French speakers in Quebec. Of recent I’ve had a change of heart. I’ve realized that the people of Quebec stand unique in the western world. The willingness of Quebecers to stand up and say they are not just proud Quebecers but proud of their history and heritage. Imagine if you will, a white person defending whiteness and our western culture. Political opponents would quickly label you a racist and member of your own party would label you a trouble maker. But when it comes to Quebec one is allowed to say out loud thinks but fears to speak.

“I’m proud of my Country and it’s history and it’s culture! I carry no shame in being Canadian. "

But alas as I’m a non French speaking white person I can only say that under my breath less I incur the wrath of the mob and of spineless politicians.

There would never be a Charter without s.33. Alberta and I suspect a few other provinces would have joined Quebec in never signing the document.

Why would they have never signed? They refused to give Ottawa the trust of the benefit of the doubt in interpreting the document. Ottawa didn't earn that trust and still doesn't have it. The Supreme Court especially gives the legal elite an unaccountable veto over everything that matters and that power isn't trusted by Quebec, Alberta, etc.

Address the trust issue and the lack of checks and balances in Ottawa, and lack of accountability, before even speaking about getting rid of the Nonwithstanding Clause.

Canada's political elites haven't earned the trust of the provinces and the people.