Andrew Potter: Sovereignty is a verb

Somewhere along the line, Canadians decided their independence was something they had by right, not something that was fought and paid for at a very dear cost.

By: Andrew Potter

There is a map that shows up on social media from time to time, and it looks like this.

Sometimes it is followed by this one:

And then maybe this one:

What’s the point of these maps? Apart from noting the obvious, which is that Canada is sparsely populated, and much of the population is gathered in cities very close to the border with the United States, they raise important questions about the exercise of political power and its legitimacy, forms of governance, and, ultimately, sovereignty. By what methods did Canada come to be, and by what right does a small and relatively concentrated group of people, most of whom live down by the Great Lakes or along the St. Lawrence River, lay claim to almost ten million square kilometres of the Earth’s landmass?

It is easy to draw lines on maps. Anyone can do it. If you want those lines to represent some sort of generally accepted reality, two things must be true. First, the people inside the lines need to see those lines as legitimate, and be willing to take the necessary steps, up to and including the use of force, to assert them against outsiders. And second, enough outsiders of sufficient global importance also need to recognize those lines.

Any student of Canadian history knows that the borders of Canada are highly contingent. Rewind the tape of the past, and there are any number of moments where things could have turned out differently. In some scenarios, Canada ends up smaller than it currently is; in others, Canada ends up larger, perhaps substantially so. And in some alternative histories, Canada does not exist at all — or if it does, we’re all speaking French.

There’s nothing that is either sinister or celebratory in pointing this out. History is a bunch of stuff that happened, and in some cases, things might have turned out differently. But again, if you know your Canadian history, you know that the process by which Canada went from a French fur trading outpost to a collection of British mercantile colonies to a continent-spanning multinational federation and parliamentary democracy was made possible only through a rough admixture of ambition, cunning, scheming, coercion, violence, strong foreign support, and, between 1812 and 1814, war.

To get to the point: Canada’s sovereignty wasn’t something we just stumbled upon, nor is it something we were happily given. It was a thing we did. We did not do it alone, though; for most of the 19th century, the main ongoing threat to Canada’s sovereignty was the United States, while the ultimate guarantor of that sovereignty was Great Britain.

That dynamic shifted over the first half of the 20th century, when the British Empire went into decline, and the United States became the dominant world power. There was a short period after 1931, while British influence was ebbing and that of the Americans was flowing, in which Canada stood more or less independent and autonomous. This largely ended in 1940; Britain was on the ropes against Nazi Germany, Canada was in Hitler’s sights, and an increasingly anxious Franklin Roosevelt invited Mackenzie King down to Ogdensburg, New York, for a friendly chat about continental security.

The agreement that came out of that meeting established the Permanent Joint Board on Defense, an ongoing bilateral advisory body that would oversee the common defence of the continent. Made up of both civilian and military officials from both countries, it meets semi-annually, alternating between Canada and the U.S., and the agenda can include any and all bilateral defence priorities. The 242nd such meeting took place in Ottawa last November; according to a DND readout of the meeting, the agenda included “NORAD modernization implementation; Arctic security; climate change; defense cooperation in the Indo-Pacific; Latin America and the Caribbean; and critical minerals.”

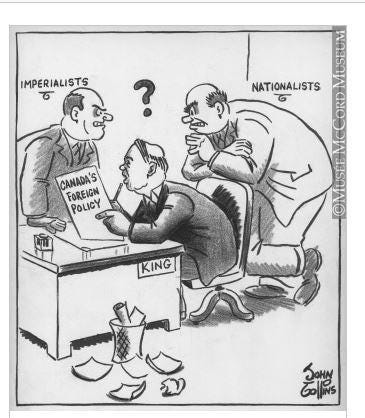

The Ogdensburg agreement was entirely necessary, but it nevertheless angered Canadians of all stripes. Canadian imperialists thought we were turning our back on Britain in her hour of need. For the nascent Canadian nationalists, we had gone from colony to nation and back to colony again in the span of a short decade. Poor Mackenzie King was stuck in the middle, trying to muddle on through.

The nationalists weren’t entirely wrong. To the extent that Canada was able to establish itself as a sovereign and relevant country in the eyes of the world after the Second World War, this relied upon the skillful exercise of a great deal of power, both hard and soft. The soft power part involved getting other countries to acknowledge and support our independence. Canada, full of confidence after making a major contribution to defeating the Nazis, threw itself into this project, helping build the new global order by joining and supporting as many new collective organizations and bodies as were on offer. The World Bank and the IMF, the UN, NATO … there was a sort of cargo-cult logic to this strategy: these organizations are made up of sovereign states, so if Canada is a member, that must mean we too are recognized as a sovereign state. A thing is as it behaves.

The hard power part was the true subtext of the bargain struck at Ogdensburg: The Americans would recognize and even defend Canadian sovereignty, on the condition that Canadians would not allow themselves to become a threat to the safety and security of Americans. This put a permanent obligation on Canadians to actually do their fair share of patrolling and defending the continent, and securing their borders.

For a few decades, this parallel track approach to Canadian sovereignty of being a reliable partner in North America and a reliable ally abroad worked pretty well. We held up our end of the continental bargain in NATO and NORAD, and we made useful contributions to a stable and increasingly prosperous international community.

But at some point, we forgot about what it had taken us to get there. We started taking the whole setup for granted. We assumed our independence as a right, something to which we were entitled rather than something that had been earned, over many decades, and at a considerable effort and cost. We squandered our soft power advantages and started acting as moralizers and scolds to our allies abroad, while flagrantly, even boastfully, free-riding when it came to both collective and continental defence.

The Liberals under Justin Trudeau didn’t start us on this trajectory, that was his father’s doing, and it continued under Liberal and Tory PMs afterward. But the past decade has seen an acceleration of Canada’s malign neglect of its most basic obligations on security and defence, even as our allies privately begged us to step up. Meanwhile, while our traditional soft-power conceits (“honest broker,” “helpful fixer,” “great convenor”) were themselves replaced by a bathetic series of after-school special morality plays put on by an Instagram account masquerading as a G7 government. The only thing that has saved us for so long is an increasingly tight-lipped tolerance from our allies, and a generally benevolent and indulgent United States of America.

We can no longer rely on either of these. We have needlessly alienated far too many of our friends, and the United States under Donald Trump will be neither benevolent nor indulgent. Those lines on the map aren’t found in nature, and they are not ours by right. Sovereignty isn’t a noun, it’s a verb.

If we want to keep the true north strong and free, we’re going to have to actually do something about it.

Andrew Potter lives in Montreal.

The Line is entirely reader and advertiser funded — no federal subsidy for us! If you value our work, have already subscribed, and still worry about what will happen when the conventional media finishes collapsing, please make a donation today.

The Line is Canada’s last, best hope for irreverent commentary. We reject bullshit. We love lively writing. Please consider supporting us by subscribing. Follow us on Twitter @the_lineca. Fight with us on Facebook. Pitch us something: lineeditor@protonmail.com

This is so on the mark. And much as many people may not want to acknowledge it, governments both liberal and conservative have done their best to hasten the decline of our ability to defend ourselves and our borders .

One of my brothers was in the army in the early 1970s, and even then our military was very poorly equipped with never enough people to do the job. Another brother was in the Navy in the 1980s and said that whenever the ship he was on went to a foreign port where the US Navy was also present, it was very obvious that our equipment was quite outdated. Another brother was in the Air force until a few years ago and while he enjoyed his time in the military, he felt that the armed forces were always challenged by first of all not enough cash, and second a horrible process for acquiring new equipment.

So the writer is correct that the decline has been going on for many years and it still hasn't stopped. And unfortunately our current Prime Minister has had no interest in building an armed force that can actually contribute because he is too busy virtue signaling and giving moral lectures to leaders throughout the world.

Much as I don't like Donald Trump and his approach to "diplomacy", this may be the only way that Canada and other nations who have neglected their responsibility to look after their defense and their borders will finally be forced to make the right decisions and spend some money on their arm forces and border controls.

What a great article! And very timely too.

Excellent. How did we allow the apologies for our history? And the attempt to erase it?

Let's start by putting the statues back up!