Andrew Potter: The Doomsday Clock gets its mojo back

The extended post-Soviet Union period lulled us into a feeling that nuclear annihilation was as retro-obsolete as big hair and rugger pants.

By: Andrew Potter

Earlier this week, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists moved the hands of its Doomsday Clock ahead by ten seconds, to 90 seconds to midnight. This is the closest the clock has ever been to midnight, and, according to the press release announcing the move: “Never in the Doomsday Clock’s 76-year history have we been so close to global catastrophe.”

If you’re under, say, 40 years of age or so, that paragraph is probably pure gobbledygook, the written equivalent of the squawk of a 2400 baud modem going through its handshaking protocols. But for those of us in the ever-dwindling cohorts of Gen-Xers and Baby Boomers, hearing about the movement of the Doomsday Clock is to be jerked back into a time marked by both profound moral clarity and deep existential anxiety.

A bit of background on the Doomsday Clock might help. It was a creature of the Cold War, founded in 1947 by some of the scientists who had worked on the Manhattan Project to raise public awareness of the threat of nuclear weapons. As the Bulletin puts it, the clock uses “the imagery of apocalypse (midnight) and the contemporary idiom of nuclear explosion (countdown to zero) to convey threats to humanity and the planet.” The decision to move or leave the minute hand of the Clock in place is made each year by the various trustees of the Bulletin, based on their evaluation of the world’s vulnerability to catastrophe.

The clock was initially set at a nice and relaxed seven minutes to midnight, and over the following few decades it was moved closer in response to clear nuclear threats, things like ramped-up testing of new bombs, nuclear proliferation, or rising Cold War tensions. During periods of detente or after the signing of arms reductions treaties, the minute hand would retreat. In 1991, it was moved back to 17 minutes to midnight after the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

For most of the second half of the 20th century, the Doomsday Clock was a healthy reminder of the most salient geopolitical fact of the era, which is that two superpowers were pointing thousands of nuclear weapons at one another.

But like many Cold War relics, the demise of the U.S.S.R. left it scrambling for a raison d’etre. In a bit of clever PR entrepreneurialism, the executive of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists turned the clock into a more generalized warning against war, climate change and other ecological or technological threats. The nadir of this shift in mission came on January 23rd 2020, when the Bulletin moved the clock’s hands to 100 seconds to midnight.

As the press release accompanying the ticking of the clock noted at the time, this put humanity “closer than ever” to catastrophe. Given that the clock had kept watch over our drive for self-destruction through the Suez Crisis, the Cuban Missile Crisis, the sabre-rattling Reagan administration, and the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, it makes one wonder just what happened in early 2020 to merit such a fearful move.

You might be forgiven for assuming that the motivation here was the declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic, but the decision about the Clock was made before the pandemic had been declared. No, in moving the minute hand to 100 seconds to midnight in 2020, the Bulletin named the ongoing problem of global security and the reality of climate change, but also the growing problem of disinformation and the general poisoning of the media ecosystem. There was no mention of a worrisome coronavirus coming out of China.

This shift in emphasis is understandable. If you had to list the big threats facing humanity, the list of obvious candidates has been a moving target. For most of the 20th century the number one threat was all-out nuclear war. That faded after the fall of the Berlin Wall, and for a while after 9/11 it looked like Islamic terrorism might pose an existential threat if not to humanity, at least to the West. That too has become part of the background radiation of modernity. Meanwhile anthropogenic climate change, a.k.a. global warming, has emerged as the most urgent and compelling concern to the human race even as rational debate around the subject has become confounded by the proliferation of fake news.

But the downside to this sort of mission creep is that it erased a pretty useful distinction, between threats to the very existence of civilization, on the one hand, and problems that humanity is going to have to work really hard to solve, on the other. Climate change is a really hard problem, with serious (though ultimately manageable) consequences. Disinformation, the loss of trust in expertise, the decline in faith in democracy — again, serious problems that we’re going to have to figure out how to deal with. Other concerning issues loom, from what to do about the global collapse in birth rates to holy smokes did AI ever get good all of a sudden.

But at worst, these are the sorts of things that could push humanity into an extended period of decay and decline. An all-out nuclear exchange is something that is of a different kind, insofar as it threatens humanity not with decline, but with near-extinction and civilizational collapse. And what the extended post-Soviet Union period did was lull us into a feeling that nuclear annihilation was as retro-obsolete as big hair and rugger pants.

The latest update from the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists is, for the most part, a helpful corrective to this. In announcing the first movement of the hands of the clock since 2020, it focuses on the all-out Russian war in Ukraine, which is about to enter its second year. Even better, the Bulletin makes a point of pinning the blame entirely on Russia — its thinly veiled threats to use nuclear weapons; its violations of international security agreements to which it is a signatory; its occupation and use of nuclear power plants in Ukraine; and so on. This is a pleasant shift from the ideological both-sidesism that marked so much of the Cold War discourse around nuclear weapons.

There’s stuff to quibble about in the release, in particular the tacked-on language about the effect of the war in serving to “undermine global efforts to combat climate change.” There’s also a good argument to be made that Ukraine’s stubborn resistance (and, soon, victory) has in fact made nuclear war less likely in the future, by making proliferation less necessary.

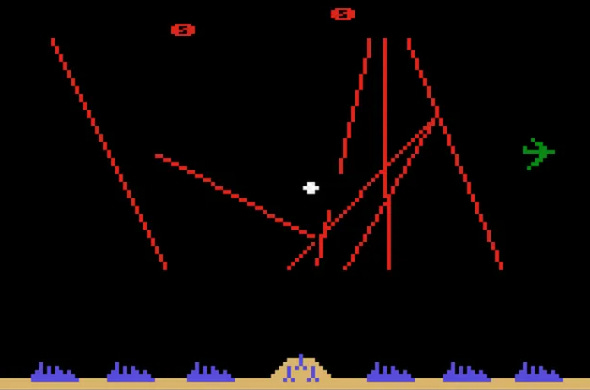

But overall, it’s nice to see the Doomsday Clock reconnect with its founding mission, namely, warning about nuclear armageddon. It’s a warmly familiar way of managing an ongoing anxiety, like watching War Games, playing Missile Command at the arcade, or walking through the mall listening to this on a Sony Walkman:

Andrew Potter is the author of, most recently, On Decline: Stagnation, Nostalgia, And Why Every Year is the Worst One Ever.

The Line is Canada’s last, best hope for irreverent commentary. We reject bullshit. We love lively writing. Please consider supporting us by subscribing. Follow us on Twitter @the_lineca. Fight with us on Facebook. Pitch us something: lineeditor@protonmail.com