Andrew Potter: What's eating liberal democracy?

What’s eating liberalism? It’s not the absence of god, it’s the lack of community.

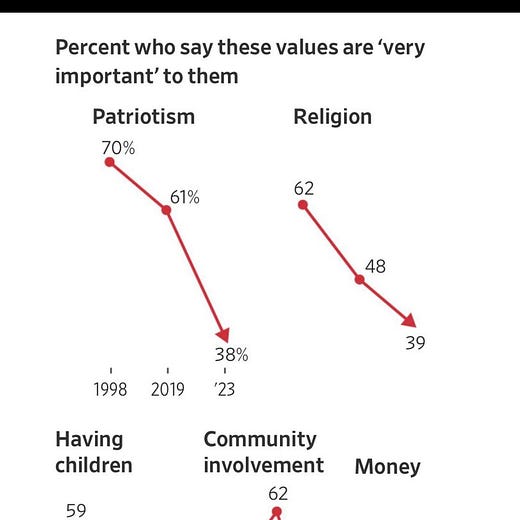

Here are some charts that were going around the social media the other day:

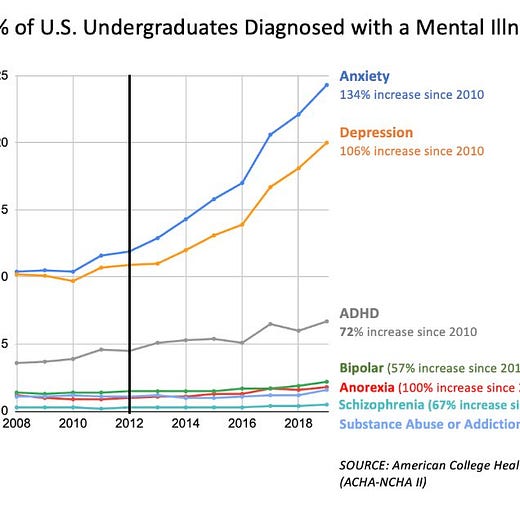

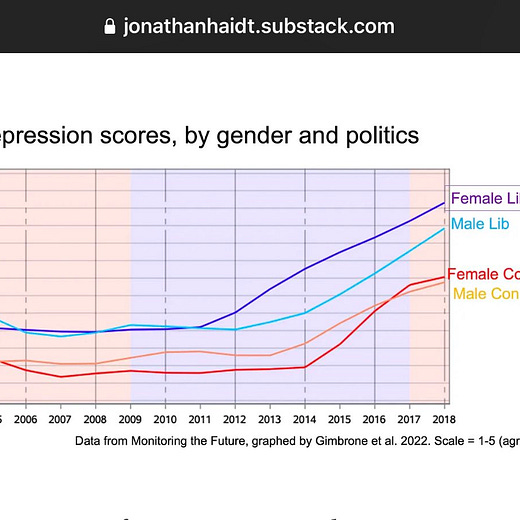

Boyle — a partner at Andreessen Horowitz — paired these charts with links to a series of reports and studies connecting these declines to a clutch of modern day problems, in particular rising levels of anxiety and depression, despair, most notably amongst the young.

As the boomers used to say, you don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind is blowing. The Western world is in a bit of a funk.

Our political systems have become impossibly polarized, our economies stagger from one crisis to the next, and the welfare state is bumping up against the limits imposed by escalating costs and diminishing state capacity. All of this comes as people are losing faith in the institutions that have served for decades as the building blocks of a cohesive society. Our reserves of social capital are depleted as numerous countries report falling levels of patriotism, religiosity, and community-mindedness. Everyone’s more or less given up on having kids, while close to a third of men aged 18-30 haven’t had sex in the past year.

These stats vary from country to country, and some places are obviously doing better than others. But the trends are grim across the board; there’s no question that, in general, people in the West are in a bad way. The debate revolves around the cause or causes of these phenomena. Is it social media? The pandemic? Housing prices, debt and precarious employment?

One possibility is that the problem lies with the modern world itself. That the basket of rights-based political individualism and consumer-driven economic capitalism might provide us with all manner of creature comforts and technological wonders, but it doesn’t give us meaning. At the dark heart of liberalism lies nihilism.

This is not a new charge, it has been around as long as there has been liberalism. Yet there’s a bit of disagreement over exactly where the problem lies. For some, from Dostoevsky to the existentialists, the worry was deeply metaphysical: that in the absence of a god, or some comparable external source of absolute morality, the only alternative is raw moral relativism.

For other critics, the complaint is more aesthetic. The consumer goods and individualistic values that liberalism promotes are seen as terribly shallow and narcissistic, with the vulgar virtues of television and cheeseburgers supplanting the higher arts of opera and the terroir.

But there’s another argument, that sort of splits the difference between the metaphysical and the aesthetic worries. This is the idea that for all its promotion of radical pluralism, liberalism is actually hostile to true difference and diversity, of the sort that permits the flourishing of distinct communities. This was the central complaint of the Canadian philosopher George Grant, whose anti-American nationalism was based not on any sense that Canada was intrinsically worthwhile, but that its more collective approach to public life would foster a communitarianism that was not possible in the United States.

Ironically, Grant’s argument was later echoed by Francis Fukuyama in his infamous essay “The End of History?”. Despite his ostensible triumphalism over the success of liberal consumer capitalism, Fukuyama was deeply worried about the impact of the loss of big narratives and shared conceptions of the good.

Ultimately, the concern over the trajectory of liberalism is not about the absence of a god, and its not about the demise of the snobbier lifestyle preferences. It is about the decline of social capital. This is something we used to talk about as a matter of profound public importance. In 2000, the sociologist Robert Putnam published a book entitled Bowling Alone, which tracked the decline of social capital in America over the course of the second half of the 20th century. Putnam looked at the ways in which Americans had become disengaged from traditional forms of community involvement — lowered voter turnout, declining levels of volunteerism, political party membership, membership in clubs, and so on — and he connected this disengagement to broader trends of democratic decline and social decay.

The book was a sensation, and it spurred a long and deep conversation, both in the U.S. and in Canada and overseas, about social capital, the tight bonds of community, and how these contribute to a healthy democratic polity. Yet despite the fact that the trends that Putnam identified have only intensified to the point where they’ve reached crisis levels, we’ve more or less given up talking about it with those terms. Who debates community as the foundation of social capital these days? How square can you get?

Actually, the problem is worse than mere indifference. When it comes to so many aspects of our civic life, we are encouraging people to adopt life-and work-styles that are actively hostile to the building and maintenance of social networks.

It has become commonplace to blame a lot of our current political malaise, especially polarization, on the twin factors of the pandemic and social media. The pandemic forced governments to make controversial and heavy-handed decisions in the name of public health, while social media fostered hothouses of paranoia and conspiracy theory about those measures.

While this is true for a relatively few hardcore partisans, the combination of the pandemic and technology had a far more damaging impact on the silent majority in the middle of it all. The pandemic lockdowns destroyed social capital across the board. Churches closed, bars and cafes went bankrupt, sporting clubs shut down, weddings were cancelled, funerals were attended by handfuls. An entire generation of high school students lost, forever, the teams, the dances, the parties, the clubs — all of the building blocks of a social life. And we replaced it all with technology; we continue to encourage “work from home” as something other than an absolute travesty.

What’s eating liberalism? It’s not the absence of god, it’s the lack of community. We lost the reflexive habits of friendship and citizenship, took a blowtorch to the little platoons of civic engagement. Some of it was probably necessary, but we shouldn’t delude ourselves about what we have lost.

We spent three years sowing the seeds of Zoom, and now we’re reaping the harvest. Fixing what we’ve done should be one of our central occupations.

Andrew Potter is the author of On Decline: Stagnation, Nostalgia, And Why Every Year is the Worst One Ever.

The Line is Canada’s last, best hope for irreverent commentary. We reject bullshit. We love lively writing. Please consider supporting us by subscribing. Follow us on Twitter @the_lineca. Fight with us on Facebook. Pitch us something: lineeditor@protonmail.com