Andrew Potter: Who is our military for?

If we are going to spend billions of dollars expanding the CAF, it has to be for something more noble than just keeping America happy.

By: Andrew Potter

It’s been a busy few weeks for news in Canada, with the anticipated exuberance of the Winter Olympics in Italy being heavily muted by both the shocking tragedy of the school shooting in Tumbler Ridge and the regular-as-metamucil drumbeat of threats against our prosperity, security, and sovereignty from Donald Trump. The Carney government is set to release a new Defence Industrial Strategy today, an implicit admission that the era of assuming the Americans will always have our back is over and that Canada may finally need to start taking its own security seriously.

But early 2026 also marks an important anniversary for Canada, and the fact that it has passed almost entirely unnoticed is a symptom of the attitudes that have made us so vulnerable to American threats in the first place.

Just around this time 20 years ago, Canadians were finally clocking to the realization that we were in serious trouble in Afghanistan. It began on January 15 of 2006 when Glyn Berry, the senior Canadian diplomat with the Provincial Reconstruction Team in Kandahar City, was assassinated by a Taliban suicide bomber. On March 4th, Captain Trevor Greene, a reservist from Vancouver working as a Civilian-Military Cooperation Officer, had his head split open with an axe by an Afghan teenager while he was talking with village elders about access to clean water and other basic needs.

Within another month, Canadian soldiers had started dying in combat with Taliban insurgents, punctuated by the killing on May 17 of Nichola Goddard, a combat engineer with the Royal Canadian Horse Artillery and Canada’s first ever female combat death. By the end of the year, 36 Canadian soldiers had died in Kandahar, a shocking multiplication of the seven who were killed in the previous five years of our mission in Afghanistan.

It is maybe not surprising that we aren’t taking note of any of this. Canadians barely cared about the Afghanistan mission even when our soldiers were fighting and dying in the Kandahar dust. What little interest there was in our activities there evaporated entirely when we lowered our flag for the last time in Kabul in March 2014. Why were we there? What did we accomplish? Was it a success? Was it worth it? These are all the kinds of questions a serious country would have asked after spending 13 years, $18 billion, and sacrificing the lives of 158 soldiers in a foreign land. But Canadians have by and large preferred to just pretend that we never went there in the first place.

If there is reason for this deliberate national amnesia about Afghanistan, it may be that the answers to these questions are, to put it mildly, uncomfortable. After all, Canada had no independent beef with the Taliban. They didn’t attack us, they were neither a threat to our safety nor to our way of life. We did not go to Afghanistan to fight for Canada in the war on terror, we didn’t go to help Afghan girls and women, or to rebuild the Afghan state. We went to Afghanistan to suck up to America.

After 9/11, keeping the Americans happy, by making it clear that Canada was a reliable security ally in the defence of North America, was close to non-negotiable for the Chrétien government. For the Canadian military, 9/11 could not have come at a better time. The CAF had endured a decade of darkness since the disgrace of its peacekeeping mission to Somalia, and Afghanistan was an opportunity for the Canadian military to get its self-respect back. Perhaps more importantly for the brass, it was a chance to earn the respect of their American counterparts.

Treating Canada’s mission to Afghanistan as fundamentally about fluffing the Americans is not the usual way to evaluate the merits of warfare, especially when it leads to the deaths of substantial numbers of your country’s soldiers. Any judgment of whether it was worth it depends a great deal on whether you accept that Canada’s strategic geography, and our more general position in the world, makes this relationship necessary and perhaps inevitable.

Either way, there are extremely important lessons Canadians need to learn from this. The first has to do with the status of our armed forces. The Canadian military has always been an expeditionary force, fighting foreign wars far from Canada. Sometimes that has been disastrous, sometimes it has been noble, but it has almost never been because Canada’s security and sovereignty was under direct threat. What our Afghanistan mission implicitly conceded was that the CAF is effectively a colonial army, whose job it is to fight and die on foreign soil on behalf of a foreign master with foreign interests.

A second point is even more vital: what we earned from this in the way of respect or gratitude falls somewhere on the short continuum between jack shit and sweet fuck all.

To see this, look no further than U.S. President Donald Trump and his various toadies, who have spent the last year threatening erstwhile allies with economic warfare, annexation, even invasion; berating these same former allies for not spending enough on their own defence; and accusing them of not being willing to fight on America’s behalf.

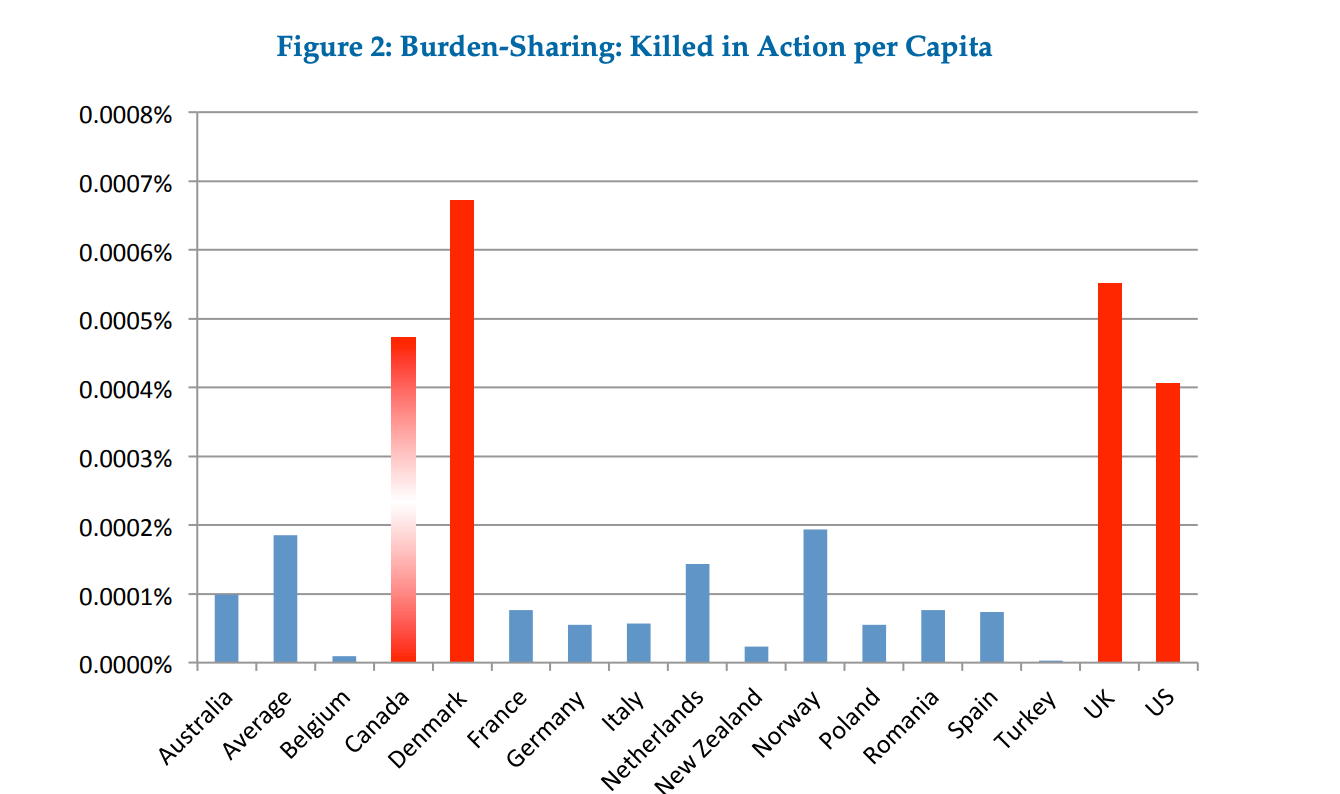

In response, political leaders, military officials, and the media in countries such as the U.K., Denmark and Canada have repeatedly brought up Afghanistan as a place where, in the not-so-distant past, America’s allies did exactly that.

This is grimy and pathetic. Bringing up your Afghanistan war dead cuts no ice with the Americans, not because they don’t think it is true, but because they don’t care. At best, this is the sort of sacrifice an imperial master just expects of its vassals, and it is certainly not the sort of thing it needs to be thankful for. But worse, it’s pretty clear that as far as Donald Trump is concerned, anyone who fought and died in Afghanistan for any reason is just a sucker.

Canada has to be courageous and clear eyed about all of this, as we look to find our way in the new “harsh reality” that Prime Minister Mark Carney spoke of in his Davos speech. We are getting ready to greatly expand our armed forces and spend billions on new equipment, including submarines, ships, fighter jets, and drones. There is talk out of DND of standing up a domestic “citizen’s army” of up to 300,000 reservists. One former chief of the defence staff has mused recently about keeping our “options open” regarding nuclear weapons. We have just signed on as the only non-European country to the EU’s new loans-for-weapons program.

Great. Bring it on, all of it. But there is one question we must answer before we start writing enormous cheques and wrapping ourselves in martial rhetoric: who is all this for? If the lesson of Afghanistan is that you can spend 13 years proving your loyalty to the empire and still be treated like an ungrateful freeloader, then maybe the grown-up move is to stop confusing defence policy with a long-running bid for American approval.

Because if we are going to rearm, if we are going to ask more young Canadians to sign up and possibly die, it should not be to try to earn the respect of a country that has already made clear it has none to give. It should be for Canada, not as a sentimental slogan, but as an actual hard-power strategic fact.

And if we can’t say that out loud, then even as we pretend we were never there, the truth is we haven’t really left Afghanistan at all.

Andrew Potter lives in Montreal.

The Line is entirely reader and advertiser funded — no federal subsidy for us! If you value our work, have already subscribed, and still worry about what will happen when the conventional media finishes collapsing, please make a donation today. Please note: a donation is not a subscription, and will not grant access to paywalled content. It’s just a way of thanking us for what we do. If you’re looking to subscribe and get full access, it’s that other blue button!

The Line is Canada’s last, best hope for irreverent commentary. We reject bullshit. We love lively writing. Please consider supporting us by subscribing. Please follow us on social media! Facebook x 2: On The Line Podcast here, and The Line Podcast here. Instagram. Also: TikTok. BlueSky. LinkedIn. Matt’s Twitter. The Line’s Twitter.Jen’s Twitter. Contact us by email: lineeditor@protonmail.com

I come from a military family. RMC accepted me in 1975. I considered the Marines during Vietnam. I chose another path — but not out of contempt for service. Out of realism about leadership and direction. My cousin is a retired Colonel. Other relatives served at sea, in the air, in artillery, in Afghanistan. I support the military fully. What I don’t support is drift.

Andrew Potter is right to ask who our military is for. Afghanistan exposed something uncomfortable: we spent blood and billions without ever explaining to Canadians what Canadian interest was being defended. Alliance is not submission — but neither is it strategy. If we are going to spend tens of billions now, expand reserves, buy submarines and jets, and talk about citizen armies, then say clearly what problem we are solving. Arctic sovereignty? Continental defence? NATO projection? Domestic resilience? Pick one. Build around it.

And whatever that strategy is, it must include an industrial spine. A country that cannot build, repair, arm, fuel, and supply its own forces is not sovereign — it is subcontracting its security. Military spending without strategy is theatre. Strategy without industry is fantasy. If we are going to rearm, let it be for Canada — not as a slogan, but as a hard, articulated national purpose.

"We went to Afghanistan to suck up to America." No, we went to Afghanistan to honour our NATO commitment to collective defence of the alliance under Article 5 of the treaty, which was invoked two days after 9/11, as documented in many places, not least of which is Dr Sean Maloney's history of the Canadian Army in Afghanistan, available via canada.ca. Pretty sure G&G themselves have previously written on this site that treaty obligations of any sort aren't a matter of discretion, regardless of the personalities or dynamics involved at the time.

I'm sorry, I generally like Potter's writing, but that's such an egregious misrepresentation of the facts that I can't take the rest seriously, and I'm surprised Gurney (being the military historian he is) let that slide. Potter's either ignorant of history, incompetent at checking his facts, or willing to play fast and loose with the truth so that he can establish the right tone for his rant. I stopped reading there. Others can consider the rest of his argument if they want but I give no serious consideration to a piece that either willfully or lazily gets the basic facts wrong. There's much more intelligent writing out there on the (very important) topic of CAN/US military relations than this.