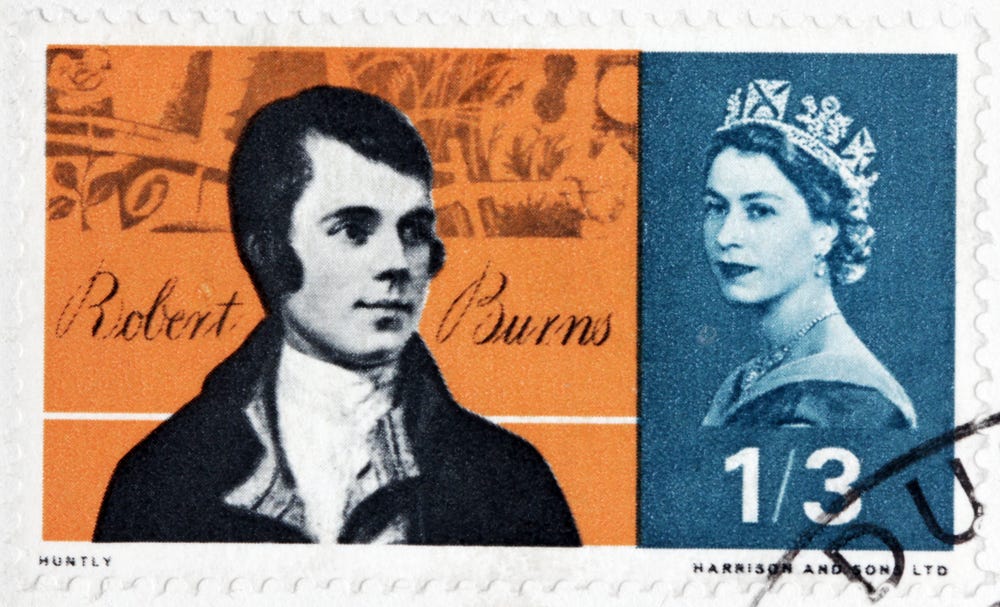

Burns was not a good man, perhaps not a great poet, but he was memorable as both

John Ivison's “The Riotous Passions of Robbie Burns” take us as close as possible to the only man who could author the unique catalogue of poems.

Book Review

By: Howard Anglin

I don’t know what I was expecting before I picked up John Ivison’s new book, The Riotous Passions of Robbie Burns, but it was not this. In my head, I’d already started composing the end of my review. Something round and pat and full of holiday hygge like: “So light the fire, pour yourself a dram of Annandale whisky, and enjoy ...” Because Ivison grew up in Dumfries, where Burns spent the last years of his life, I suppose I expected a more personal narrative, not a work of historical fiction. One expects fiction from political journalists in their day jobs, not in a labour of love composed off the clock.

What I really expected was more of Burns’ poetry — the source of his enduring fame, after all — and less of his person, which was the source of his contemporary infamy. Instead, Ivison gives us something more interesting and unusual: the poetry of Burns’ non-poetic speech. Ivison has taken snippets, and sometimes cribbed whole paragraphs, from Burns’s copious surviving correspondence and woven them into dialogue that carries the story of the poet’s stay in Edinburgh between 1786 and 1788. By putting Burns’ actual words into his mouth, even if sometimes out of context, Ivison gives the reader a direct and plausible impression of Burns the man. We hear verbatim both the coarse tavern wit and the elemental passion that spilled into his prolific verse — sometimes into unprintable doggerel (literally: his poems later collected as The Merry Muses of Caledonia were banned as obscene in the U.K. until 1965), sometimes into achingly beautiful verses like “Flow gently, sweet Afton” or “Ae Fond Kiss.”

Ivison’s book sets us in Edinburgh at a time when, as he writes, “it was said if you stood at the Mercat Cross with a pistol, you could hit 50 geniuses, 50 bankers, 50 lawyers and 50 rogues at any given hour” (no doubt allowing for some overlap between latter two categories). Our narrator and guide is the newly-arrived and impressionable young lawyer’s apprentice, John Bruce, a composite and Zelig-like stand in for many young men of the poet’s acquaintance. (The only record of Burns meeting a John Bruce that I can find was a Rev. John Bruce, Minister of the Highland town of Forfar, whom the poet found “pleasant, agreeable and engaging.”) Through Burns, Bruce and the reader are introduced to the ways of women, drink, the printing business, drink, aristocratic libertinism, and a little more drink.

The two main plots, such as they are, link Bruce and Burns to the notorious escapades of Deacon Brodie, whom Burns met in real life, and to the poet’s long, futile, but apparently sincere courtship of the unhappily-married Agnes (sometimes Nancy) Maclehose. The real life letters between Burns and Maclehose, written under the pseudonyms “Sylvander” and “Clarinda,” make for moving reading and, in this telling, for surprisingly convincing dialogue between Burns and Maclehose and between Burns and Bruce. The text is especially affecting when the poet is in the grip of what he called his “low spirits & blue devils” and his usually florid speech turns fatalistic, brooding, and palpably human.

But the plots are not the point of this charming book; they are frames on which to hang Burns’s words and excuses to showcase Edinburgh as it was coming of age as an intellectual and commercial capital, with all the growing pains that entailed. Filling the city with historical characters, Ivison shows us the city as Burns found it, its population bursting out of the overbuilt medieval closes and wynds that lined the Royal Mile running down the hill from the castle and spreading across the North Bridge to New Town and down to the sea port at Leith.

Thanks to the Scottish Enlightenment, and especially to David Hume, Scotland was casting off the superstition of an earlier age — something the book’s characters mention several times — but rationalism was not religion’s only replacement. Alongside Hume’s cool Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding came a new Romantic national mythology. It began with James Macpherson’s sensational “Ossian” poems–unread now, but a European bestseller for a century after their anonymous publication — and was filled out and polished by Walter Scott’s equally successful Waverley novels. In between Hume and Scott, both temporally and temperamentally, came Burns, the bard of a post-Enlightenment and proto-Romantic Scotland.

Robbie Burns’ genius was rough, expansive and irrepressible. He was a poet of romantic individual love and of Romantic universal love; of the old, wild country and the latest learned treatise. He could as easily capture the carefree sylvan “banks and braes o’ bonie Doon” as convey Adam Smith’s ideas in demotic verse. So Smith’s conviction that “If we saw ourselves in the light in which others see us, or in which they would see us if they knew all, a reformation would generally be unavoidable,” becomes in the poet’s hand the memorable lines from ‘To a Louse’: “O wad some Pow'r the giftie gie us / To see oursels as ithers see us! / It wad frae monie a blunder free us, / An' foolish notion.” In his greatest works he married the high sentiment of Edinburgh and the low speech of his country roots in revolutionary poems like “A Man’s a Man for A’ That.”

Burns and his verse have haunted me from birth (we share a birthday), or at least since my 11th birthday, when I was gifted his complete works by Scottish friends of my family. I read it several times, and even managed to memorize most of the boisterous “Address to a Haggis,” which, fortified by enough whisky, I can recite in an accent that butchers the Scots worse than Cumberland. His oeuvre is a mixed lot (Burns was as promiscuous with his pen as with his pintle) but the best has a staying power that is undeniable. There’s a reason there’s a statue of Burns in almost every major city from Halifax to Victoria, and it is no exaggeration that in carrying his poems in their hands and in their heads as they ranged across the British empire, Scots carried the soul of their country with them.

Even today, as the Scottish government is threatening a second independence referendum in less than a decade, it’s not surprising to hear nationalist leader Nicola Sturgeon appeal to Burns. In 2019, Sturgeon ended her speech to her party conference with the rousing promise that, “In the immortal words of Robert Burns, ‘It is comin’ yet for a’ that.’” That she was referring to her small-minded movement to exit the United Kingdom while Burns was referring to the universal brotherhood of man is an irony befitting the legacy of the mercurial, contradictory poet. (It’s also about right for an independence movement — and here I part ways with both the radical Burns and the patriotic Ivison — based on a difference of accent and a Mel Gibson movie, which makes about as much sense as Quebec separatism if Quebecers spoke English.)

Burns was a puzzle.

He loved women and wooed them passionately, but could discard them coldly and suddenly, even when they bore him children; he was a revolutionary and Scottish nationalist who collected taxes for the Hanovarian usurpers; he extolled a Jacobin brotherhood of man, but came close to taking a job managing a plantation in Jamaica; and once the life of the taverns and salons of Edinburgh, he died hunched and broken by farm labour at 37 in Dumfries. He was not a good man, and perhaps not a great poet, but he was undeniably memorable as both. He is a hard man to like at a distance, but all the contemporary testimony records his incomparable magnetism. I guess you had to be there. Ivison’s gift is to take us there, or as close as possible, and to show us all aspects of the only man who could believably author Burns’ unique catalogue of poems.

So light the fire, pour yourself a dram of Annandale whisky, and enjoy.

Do you have a Canadian non-fiction book you'd like to see reviewed? Well, write it yourself. We at The Line are neck-deep in books we have been diligently meaning to read and review. Send us a note at lineeditor@protonmail.com

The Line is Canada’s last, best hope for irreverent commentary. We reject bullshit. We love lively writing. Please consider supporting us by subscribing. Follow us on Twitter @the_lineca. Fight with us on Facebook. Pitch us something: lineeditor@protonmail.com