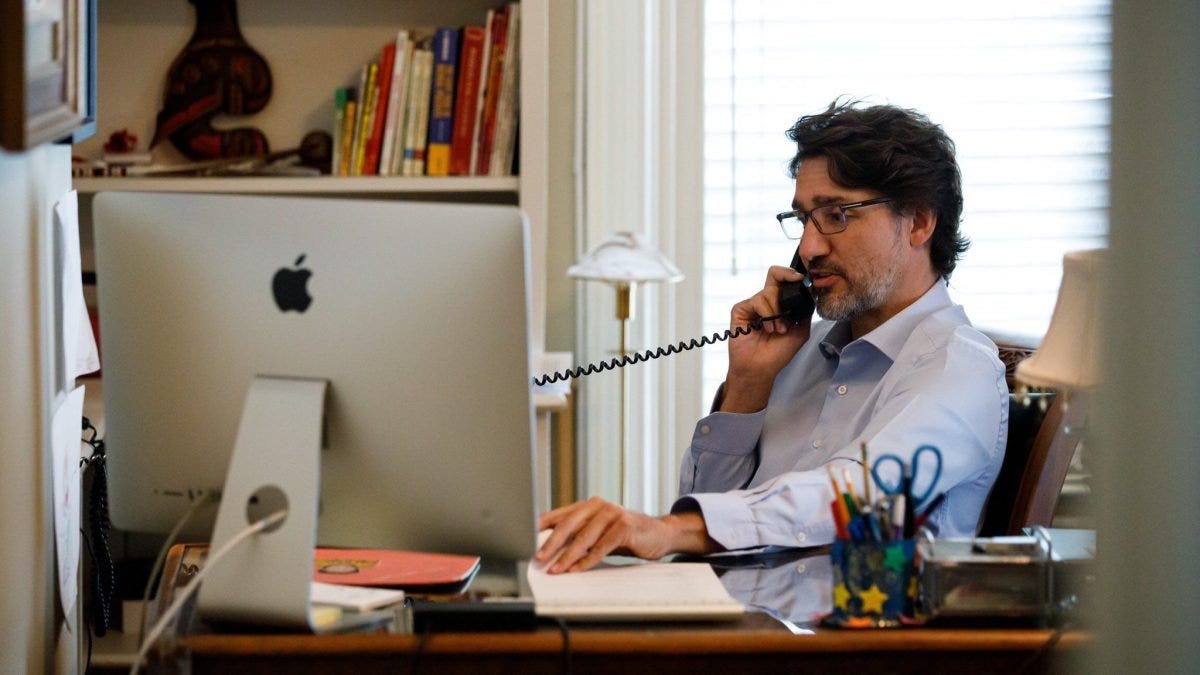

Dispatch from the Front Line: Justin Trudeau called us, and he'd like you to subscribe today

What we assume the PM wants you to know; a leak in Alberta; and why Canadians can't cheat their way to decent government with garbage leaders

Well, happy Friday, Line readers. We hope you had a wonderful week. Even if it wasn't so great, hey, at least you're having a better Friday than some idiot in the prime minister's communications office.

In case you missed it, just before five (Ottawa time) Friday evening, the PMO released a readout — a summary — of a telephone call between Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Conservative Erin O'Toole, leader of the official opposition. The readout was notable for relating that the PM chastised O'Toole for "misinformation" peddled by Conservative MPs.

There was a big problem with this: the readout was itself misinformation. Because the call between the two leaders hadn't happened yet.

The embarrassing mistake was confirmed by the PMO shortly thereafter. The PMO, blaming a staffing error, admitted that a "placeholder" of the conversation had been erroneously released.

In a similar spirit, The Line would like to release this placeholder of a future call between Mr. Trudeau and our editors:

PMJT: Hello? Are you there?

The Line: Yes, sir, we're here.

PMJT: Hi guys. I just wanted to say how much I love your stuff. I've subscribed, and I think everyone should do the same. Right now. Subscribe to The Line.

The Line: Thank you, Prime Minister. And keep the beard.

You gonna just ignore what our elected leader is saying, folks?

Over in Ontario, the second wave of COVID-19 triggered a different kind of political kerfuffle. Bonnie Lysyk, the province's auditor-general, released a “scathing” report into that province's handing of the pandemic.

We have nothing in particular to say about the report, beyond noting, as we have before, that the provincial response was imperfect. Lives were needlessly lost. Read the report if you want. It will confirm whatever beliefs you already have, we're sure.

We're skeptical that a different government would have done much better. The challenge of coping with COVID-19 isn't a partisan challenge, it's a human-nature challenge. If we were all just programmable androids, we'd have crushed COVID-19 into dust in the first four weeks. But we aren't. We're stubborn meatsacks, essentially unchanged from the moment we decided to try living in caves for a while and discovered it was an upgrade from the plain.

We don't like being told what to do. We insist on being social even when we shouldn't. We refuse to do basic things like wash our hands or wear a mask properly. Most of all, always, always think that it's OK to do the same things we want other people to avoid.

What is interesting about the Lysyk’s report is how many people across partisan lines expressed anger at the way government officials like auditors general are stepping outside their lanes. Ford led responded to Lysyk’s report with rare anger, and noted that the critique fell outside her mandate. But beyond Ford and his elite clappers, there was a surprisingly negative reaction to the auditor general’s poke all around.

We at The Line generally agree with this. Independent oversight and scrutiny is essential, but within narrowly defined limits. Within those limits, by all means, go to town! Savage the bastards. But never forget that no one elected you to anything.

The real story here is one of declining faith in our elected officials, and a preference among the public to trust in "experts" in any field. We like experts! Experts matter and should be routinely consulted. And politicians should absolutely fear the wrath of the independent officers who watch over their work.

But the growing faith in, and even preference for, experts over elected officials reflects a failure of us, the voters, to put the right elected officials into power. One of the reasons that Canada has not performed as well as it should have during this pandemic is that our politics (and politicians) are often unserious.

We haven't gone quite as far as our American siblings, who are just wrapping up a four-year term of leadership by a reality TV star, but the problem is broadly similar. We tolerate a low quality of political candidate because, for most of us, politics is a low-stakes game. The range of diversity in Canadian political opinion is so narrow, and proposals differ so mildly, that the matter of which particular bums occupy which specific seats in the big fancy votin' room doesn't matter much.

But sometimes, it matters a lot, like, for instance, now. And now we're finding that not only do we not have all the right people in the right jobs, we don't even have many of the right kind of people — serious, thoughtful, honourable and dedicated. We have some, but we celebrate those people in public life specifically because they're the rare exceptions.

That's why we put so much faith in experts and independent officers: it's a cheat. Canadians have deluded themselves into thinking we can get away with an absolutely garbage array of elected officials as long as we insert a few non-elected grownups into oversight and advisory positions.

That's not how democracy works. You can have the best public-health experts, and world-leading economists, and a professional civil service — but none of them will haul our asses out of the fire in real emergencies if our elected officials continue to take their jobs as seriously as a fart joke.

Elect clowns if you want, but don't you dare act surprised when our response to unforeseen emergencies looks like a circus.

On the matter of circuses, much hubbub in Alberta with the publication of a major scoop by the CBC. The Edmonton branch of the MotherCorp remains the most prolific outlet for investigative journalism in Alberta, and reporters Jennie Russell and Charles Rusnell know how to scoop the dirt.

This week, the degree of political control directing the province's COVID-19 response was revealed in 20 recordings of conversations that took place in the Emergency Operations Centre.

From the story:

"Taken together, they reveal how Premier Jason Kenney, [Health Minister Tyler] Shandro and other cabinet ministers often micromanaged the actions of already overwhelmed civil servants; sometimes overruled their expert advice; and pushed an early relaunch strategy that seemed more focused on the economy and avoiding the appearance of curtailing Albertans' freedoms than enforcing compliance to safeguard public health."

We at The Line are of two minds about this one.

The first mind is preoccupied solely with the innate nihilistic glee common to all journalists: "Whee, secret tapes! What a scoop!"

The role of the CBC is straightforward. Releasing information in the public interest is entirely merited. The story presents absolutely no challenges to any journalistic ethics, and we would have proudly published them ourselves if such a hot ticket had landed in our inboxes.

The contrary opinion, however, has to concede that the numerous individuals who have expressed dismay at the recordings do have a fair point to make. Many who have worked in government or civil service from across the partisan spectrum were horrified that confidential conversations of this nature would be revealed to the public, presumably to damage the Health Minister and Premier Jason Kenney.

That's because while the tapes are within the public interest to publish, there is no actual scandal in them. The sizzle of this story is derived almost entirely from ignorance of how decision making operates within government.

Public health officials work at the pleasure of their premiers. They are accountable to the Health Minister. It's the civil service’s job to advise elected officials, and it's the responsibility of elected officials to take or discard that advice, weighing any number of factors including public sentiment, economic realities, and government capacity. This is why meetings of this nature are confidential: we want civil servants to lay out their positions honestly and candidly. And then we want our elected officials to make the call. It's entirely normal for a health minister to act against the advice of his health officials, and there are perfectly valid reasons for him to do so.

Ultimately, it's the health minister — not the public health officer — who is accountable to the public for the consequences of those decisions. Which is why the people of Alberta can fire Health Minister Tyler Shandro, but not Chief Medical Officer Deena Hinshaw.

Hinshaw herself said this explicitly in that same CBC story:

Her job is to offer "a range of policy options to government officials outlining what I believe is the recommended approach and the strengths and weaknesses of any alternatives.

"The final decisions are made by the cabinet... [I] always felt respected and listened to and that my recommendations have been respectfully considered by policy makers while making their decisions."

In fact, if the tapes demonstrate one thing, it's that Hinshaw herself has a correct assessment of her own role in government, and also a nuanced grasp of the challenges that governments face when deciding how — and how hard — to enforce stringent lockdown measures that have a significant economic and psychological impact.

Clearly, someone in the civil service with a bitter finger on his or her iPhone's record button believes that Kenney et al are putting too much emphasis on the economy at the expense of public health. Such people are within their rights to feel that way. They're also free to put their names on a ballot and gain the trust of the electorate to make these kinds of decisions on our behalf.

We at The Line encourage and welcome them to do so.

Roundup:

Fraser Macdonald, slightly ahead of this week’s vaccine-panic news cycle, noted that there really isn’t much sign of urgency in Ottawa, and that will get Canadians killed: “While Canadians watch in horror as COVID ravages the U.S., we must not fall prey to the trap of believing that everything in Canada is automatically better as we often do when discussing health care. Yes, we’re taking more precautions on mask wearing and social distancing, but when it comes to vaccine distribution (and, almost certainly, approval once we get to that stage), we are miles behind.”

The Line did a Q&A with Aaron Reynolds, a man who makes Captain Kirk and birds swear on the Internet and profits off of this, who somehow got flagged by an algorithm that concluded he was a threat to U.S. security. “The amount of content on [social media] sites is huge,” Reynolds explained. “You can't possibly have actual human beings monitoring all of it in real-time, so you rely on the computer code to flag problems. So it sees my post, and it goes, well, a quarter million people saw it, 700 liked it, it's mostly being consumed in the U.S., it's not from the U.S. So throttle it. It's bad.”

Matt Gurney noted that the Liberals, self-styled champions of evidence-based policy, are pulling their “military style assault weapons” ban right out of their bottoms. “It's a bad policy, aimed at the wrong people and the wrong problem,” Gurney said. “One suspects that the Liberals’ oft-stated commitment to listen to the experts and the frontline workers fizzles when said experts and workers disagree with a preferred policy. In that case, well, the government knows best.”

And Jen Gerson dropped a heapin’ helpin’ of truth on us, reminding us of what we discussed last week in our dispatch to you: conspiracy theories invert the natural order of things. “A conspiracy theorist imagines a small cabal of hyper-competent global elites pursuing a nefarious and targeted goal,” Gerson explained. “It's a total inversion of what people like me see every day: most governments are run by an enormous number of well-intentioned people of middling talent constantly at each others' throats. Most of the real power over individual lives tends to devolve to more local authority. The long-term refugee strategy of a UN subcommittee is unlikely to make any difference at all to your life — especially as almost nothing they come up with will ever be seriously entertained by even this federal government. By comparison, if your local city council decides to declare the road in front of your house a snow-route, your life is going to be hell for the snowy side of the year.”

That’s it for us this week, Line readers. Do us a big favour and heed the advice of what we assume the prime minister would say if he gave us a buzz: subscribe today and let us keep doing what we do here.

And if you don’t like anything you’ve read here tonight, well, hey. Staffing error, right?

The Line is Canada’s last, best hope for irreverent commentary. We reject bullshit. We love lively writing. Please consider supporting us by subscribing. Follow us on Twitter @the_lineca. Fight with us on Facebook. Pitch us something: lineeditor@protonmail.com

Regarding the leak in Alberta, I think there's a conflict between the idealistic view that all government discussions should be transparent and public (instead of "behind closed doors") and the realistic view that running a government - discussing and arguing about the full range of options, not just the one that the government eventually pursues - requires confidentiality. As you note, the negative reaction to the leak was from across the political spectrum, and especially from people who have worked in government.

Jean-Sebastien Rioux, responding to a journalist who said that "habitually weighing these factors behind closed doors is concerning": "I understand why this would be your view. Another view is that the government and civil servants must be able to be candid. Add this to why there is Cabinet confidence. If all that opens up to public scrutiny in real time, then what you get is Question Period."

At the federal level, I have similar concerns about the Parliamentary health committee requiring the government to hand over all memos, emails, and documents relating to the pandemic response. Paul Wells: "That’s just one of seven wide-scale fishing expeditions listed in the motion. All requiring massive deployment of government resources. All with potentially zero utility even to the motion’s stated purpose, because if this committee sat until Doomsday it would not be able to examine or discuss the thousandth part of the haystack this motion would order up." A recent news article says that there's probably close to a million pages of relevant documents, and the Parliamentary law clerk's office can only process about 50,000 pages a week. (Which still seems insanely fast to me.)

Well, "Independent oversight and scrutiny is essential, but within narrowly defined limits" is eyebrow raising, to be sure.

What's the public interest case for "narrowly defined limits" in regards to non-partisan, independent officers of legislatures, like auditors general, parliamentary budget officers, and commissioners of the environment and sustainable development?

I wonder, too, if the partisan, politically-imposed "narrowly defined limits" standard should be applied to other practitioners of ostensible "independent oversight and scrutiny," too, such as journalists and researchers? What say you? I recall the Stephen Harper Conservatives imposing such a regime on government researchers and scientists. Better not to bother citizens with facts.

Lastly, what I wonder would have been Ontario Premier Doug Ford's response regarding "narrowly defined limits" if Auditor General Bonnie Lysyk's report had been full of praise for Ford's government's handling of COVID-19? Would he have been in high dudgeon about praising the government being outside of the AG's mandate?

Independent, non-partisan officers of legislatures charged with providing oversight and scrutiny do a valuable public service when they, in the interest of the public, go beyond narrowly defined limits when they deem it necessary and useful. Let the public decide what credence to give their views, just as they do with journalists' musings and scientists' findings.