James McLeod: It's time to ask ourselves what we want 'online privacy' to mean

In complex systems run by innovative capitalists, if you create a rule intended to directly solve a problem, you’re likely to create new, maybe worse, problems.

By: James McLeod

A company called Autonomous sells chairs and desks for the work-from-home crowd, and they have an interesting marketing strategy.

When you go to their site, the products conspicuously display logos of prominent tech companies. Under the listing for the ErgoChair Pro, the company boasts “2,700+ orders from Google employees.” Other items similarly claim to be purchased by legions of Apple, Microsoft and Facebook employees, among other recognizable tech company names.

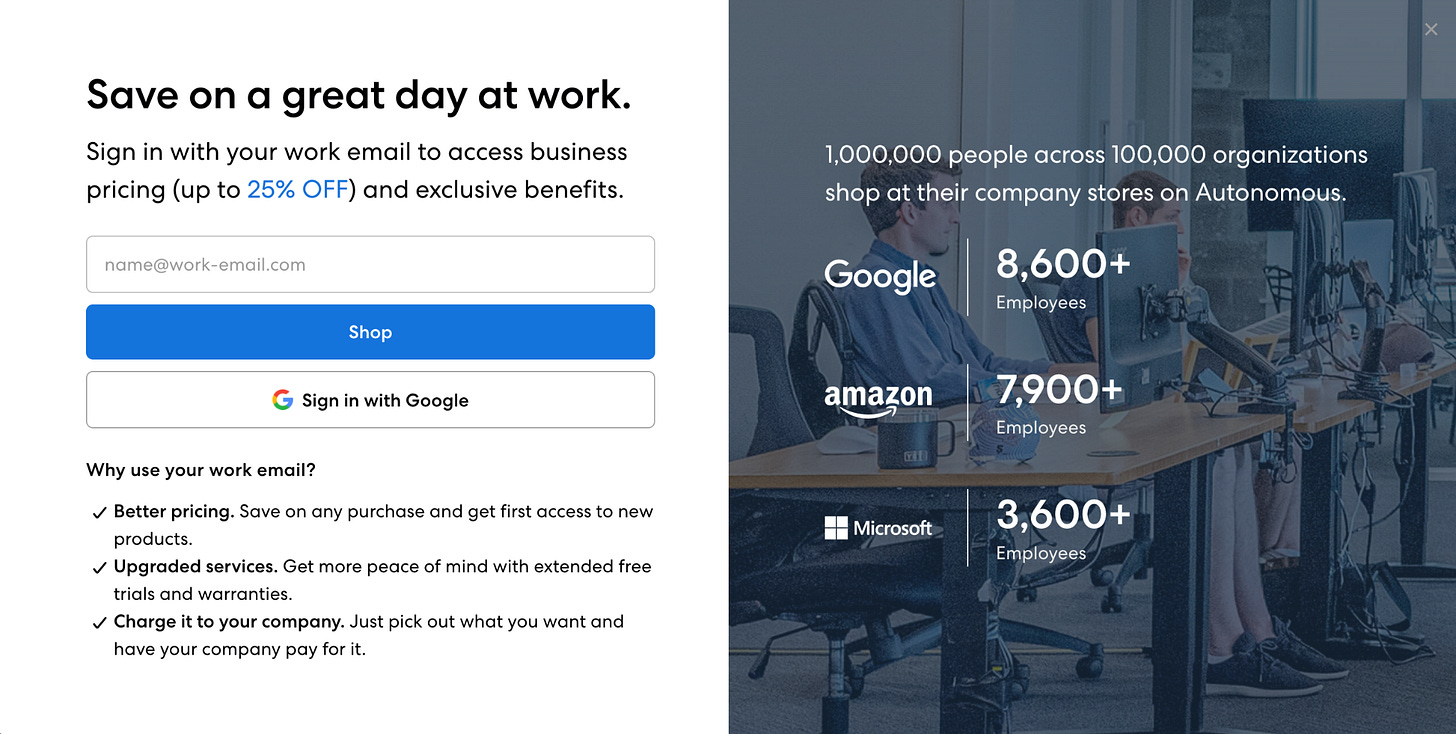

But Autonomous has a sneaky trick. When you click on an ergonomic chair to see details, the website prompts you to “Sign in to unlock business pricing.” In particular, the company very pointedly tells you to sign in with your work email to receive business pricing.

Now, I work at a business council that employs fewer than 20 people, so I didn’t expect any special discounts, but out of curiosity, I put in my professional email address to see what happened. For starters, the $699 chair I was looking at was knocked down to $536.

What’s more, the product page now looked a little bit different:

Dana is a colleague. I messaged her to tell her what I was seeing. She was a bit surprised:

It doesn’t take a genius to see what Autonomous is doing here.

I put in my work email, and they matched it up with another email with the same domain name. The website then displays the name of one or more coworkers who bought the same product. I send Dana a message, and she says she likes her chair. Assuming they make a quality product, Autonomous gets a powerful endorsement from somebody I’m likely to trust.

As a side benefit, Autonomous also gets to boast about Google and Apple employees buying their products, although I do wonder if somebody will take notice eventually and then they’ll get a litigious letter about using the tech companies’ trademarks on their website at some point in the future.

Anyway, the marketing worked on me. In the end I bought the chair.

Data and Privacy regulation

Now, I think it would be perfectly reasonable for somebody to run through this experience and find it all creepy. Dana bought a chair, and while the Autonomous terms of service give them enormous latitude to use your information for marketing purposes, Dana didn’t know her name and her purchase would be used in this way.

I can imagine somebody having this experience and saying, “They should make this illegal. This is why we need privacy laws.”

Maybe, but I’m not sure.

What Autonomous is doing is very obvious and simple. Because both our emails had the same domains, they matched ‘em up and wrote a bit of software to leverage Dana’s purchase to make me more likely to buy. It’s easy to see all the moves.

For most data-driven marketing, that’s not the case.

We live in a world today where many reasonable people believe that Facebook is listening constantly through the microphone on their phone and analyzing their conversations to target ads at them.

We live in a world where a single company operates the world’s default search engine, the most popular web browser, the most ubiquitous mobile operating system, the world’s largest video streaming platform, a ubiquitous email service, and this company made US$76 billion in profit in 2021, almost entirely based on selling targeted ads.

My point is that I have no idea how Google works, but they probably have access to more data than any single organization in all of human history, and they’re using it all to sell targeted ads, which is a sanitized way of saying they’re using that data to try to steer your behaviour in the most effective ways they can, at the behest of whoever is willing to pay them.

Facebook does this too.

These are incredibly powerful systems that are also astonishingly opaque. We don’t know how they work, really. Heck, Facebook doesn’t understand how Facebook works sometimes.

By comparison, the little endorsement trick that Autonomous is using is … adorable.

Peeking behind the curtain

I know a little bit about this stuff because a couple years ago while I was working at the Financial Post, I discovered that the Tim Hortons app was silently tracking my location in the background, and using the geolocation data to infer where I lived, where I worked, when I went on vacation, and whenever I visited one of Tim Hortons’ competitors.

Recently a team of Canadian privacy commissioners published a formal study confirming my findings, and concluding that Tim Hortons broke the law.

Arguably Tim Hortons’s biggest mistake was that they didn’t lie to me when I submitted a formal request to see all my data. Sure, that would’ve been illegal, but the company was already breaking the law.

And if they’d said “Nope, we don’t have geolocation data on you,” I would’ve been hard-pressed to prove otherwise.

What’s more, the Tim Hortons case does a good job of demonstrating how staggeringly impotent data governance enforcement in Canada is.

The privacy commissioners who investigated the company couldn’t levy fines because they don’t have that power. They’re also constrained in who they investigate, and apparently it takes two years to get the job done.

We were told this week that the privacy commissioners are nearly certain that other companies are doing the same kind of invasive tracking, but until the laws change to allow for a more effective watchdog agency … ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Unintended Consequences

I don’t know the right way to regulate data and privacy. I know in Canada we will likely see some kind of data-privacy legislation introduced by the federal government later this year. My current employer will have a policy perspective on the issue, so I’m not going to voice an opinion here on what I’d like to see in that law.

(Either I’d be shilling for my employer or I’d be dissenting and undermining them, and either way I think it’s beside the point I want to make.)

Without weighing in on what the rules will be, I think it’s worth taking a minute to think about what happens when we make rules right now.

I’ve been thinking a lot about an experience I had with Airbnb recently, when I tried to book a flat in Paris for a vacation. I submitted the booking and the host sent me a message saying that she could offer a cheaper rate if I wired her the money outside of Airbnb.

The host explained that France limits short-term rentals on platforms like Airbnb to 120 days per calendar year. She said she was close to her limit and so she couldn’t take my booking through the site, but she’d still rent me the place if I sent her money directly.

I know this is a common experience because a family member had the same thing happen to them when they booked a place in London, which imposes a 90-day limit.

Cities have recognized that Airbnb has some downsides, and politicians have moved to regulate.

And now, as a consequence of that regulation, Airbnb users are being asked by strangers to just email more than a thousand Euros to them blindly on trust, and if the apartment doesn’t look like it did in the listing, or if there’s no apartment at all when the traveller arrives, they’re just screwed.

When this happened to me, I reported the listing to Airbnb as a flagrant violation of their terms of service. When I checked back a few weeks later, the listing was still up.

Strictly in terms of maximizing profit, this makes sense: Airbnb’s financial interest in Paris is for this host to rent a flat for the 120 days allowed by law, and pay the platform their fee. If the platform can also act as a listing service for a shadow market beyond the 120 days, it still benefits Airbnb because they continue to act as the de-facto booking platform everyone goes to when they’re looking for a place to stay.

Presumably this Airbnb host has to be creative when she files her taxes at the end of the year, and if she was audited she’d be in trouble.

But all in all, it’s in everybody’s interest to let the shadow market flourish, even though it steers users toward potential fraud and unsafe situations with no avenues of recourse.

My hunch is that this is all an inevitable consequence of the 120-day limit. I think hosting on Airbnb is a lot of work, and it only makes sense if you can rent a property (or maybe many properties) for a lot of nights each year.

The theoretical person who has a prime Paris flat that they live in for eight months, but rent out for 120 days each year is probably a very rare individual indeed. There probably aren’t enough people like that to meet customer demand and sustain Airbnb’s business.

French officials could’ve banned Airbnb entirely, or could’ve developed a more rigorous regulatory scheme where hosts need to register with governmental authorities or something so that regulators would be able to see the shadow-market activity.

Or, I suppose, in theory you could have French officials going undercover and pretending to be regular tourists booking Airbnb stays in Paris, and then busting the people who break the law. On the other hand, when that happened to Uber the company responded by writing software specifically designed to deceive regulators.

My point is just that in incredibly complex systems run by innovative capitalists seeking to drive growth and sustain profitable businesses, if you create a rule intended to directly solve a problem, you’re likely to create second-order effects that might be as bad or worse than what you intended.

Put another way: If you were to make a simplistic rule to ban the little Autonomous trick that linked Dana’s purchase to me, the result would probably just be that Autonomous had to shift its marketing strategy to buying more Google and Facebook ads.

All that would really do is squash a simplistic data/privacy issue and exacerbate a vastly more complicated, pervasive privacy situation.

Some concluding thoughts

Technology is wonderful. The internet lets me laugh with my niece on the other side of the country through a video call. During the pandemic, e-commerce and communication technology saved countless lives by allowing people to distance and stay safe.

The uneasy feelings so many of us have about our devices comes from a lack of trust, at least partially because we occasionally see a darker side of the technology we use in stories like Tim Hortons tracking 1.6 million people using their app.

Smartphones and internet services are wonderful tools, but they need to be trustworthy.

It seems to me like a lot of the conversation about tech regulation is about people trying to come up with rules that’ll improve things. More and more, I think that’s the wrong way to think about it.

The starting point of the conversation needs to be thinking about what a healthy, trustworthy data and privacy ecosystem would look like.

We got a hint of this with the Tim Hortons investigation this week. The privacy commissioners concluded that Tim Hortons misled users by telling them the app only collected location data when it was open (but in fact it was collecting location data in the background.)

But more importantly, the investigation concluded that even if Tim Hortons had been truthful, it would’ve violated privacy guidelines because the amount of data collection was so wildly out of proportion to what the app actually needed, it represented a privacy invasion even if the company worded their terms of service to technically obtain user consent.

This is how I think it should work.

I don’t have a strong conclusion about what’s right and what’s wrong. There’s no satisfying end to this essay. It’s just an anecdote about a chair, and a coffee company, and a vacation rental property, and reflecting on whether some of those companies are abusing our trust. I bought the chair from Autonomous. It’s … okay, but I wouldn’t enthusiastically recommend it to a colleague. Regardless, Autonomous will do that on my behalf anyway.

With new legislative proposals about privacy regulation likely later this year, it’s a good time to start thinking about what you want from it.

James McLeod is a Toronto-based writer and communications professional. From 2018 to 2020 he covered Canadian tech for the Financial Post.

The Line is Canada’s last, best hope for irreverent commentary. We reject bullshit. We love lively writing. Please consider supporting us by subscribing. Follow us on Twitter @the_lineca. Fight with us on Facebook. Pitch us something: lineeditor@protonmail.com

This is a solid take on a really difficult topic!

A lot of misinformation and potential 'foreign interference' appears to be groups using these commerically available services to target people in very much the same way that other advertisers do. Because of the huge amount of data gathered, it's surprisingly effective and, more importantly, relatively cheap compared to what used to be available. We're giving private companies access to huge amounts of data, which they are free to 'sell' to whomever. But, keep in mind, the same services are enabling a whole bunch of small businesses who would never have access to potential buyers at this scale and for this price. So, "ban everything" is probably also not the answer.

I think we need a couple of things.

First -- we as individuals need clear language on what data is being collected and how it is being used. We also need an easy option to opt out. That's a LOT harder than it sounds. EU has tried a similar regime and apparently companies are finding ways around it. But, it's what we need to be aiming for. Moreover, the nature of the transaction we are having with data giants needs to be clearer. We are getting services (search, email, social networking, etc) in exchange for our data, but we have no idea if that exchange is a 'good deal' or not. Is my data on its own worth anything? Should I be expecting more -- or am I actually getting fair exchange? Markets function well when players are informed. Right now, the companies have all the information and we -- the users -- have nearly none. Change that equation and people may make different choices (and it may enable better competitive options).

Second -- we need third party researchers to be able to 'audit' what data giants are doing with data. That means allowing academic researchers and others to dive into the data and algorithms and understand what's happening -- something the companies themselves may not even know. That will allow us to assess social benefit and harm and start having better public policy discussions on minimizing harms and maximizing benefits.

Right now, this whole realm is a bit of a black box. I think that trying to regulate something we don't even really fully understand (which is what Canada is doing) can itself create a bunch of harms. Let's make these companies share more about their businesses, inform users and make smarter public policy. The longer we wait to do this, the more problems we're going to have.

Thank you James for that article.