James McLeod: We treat books as holy objects. They’re just ink and paper

Books are just a data-storage device. It's the act of reading that is worth celebrating.

By: James McLeod

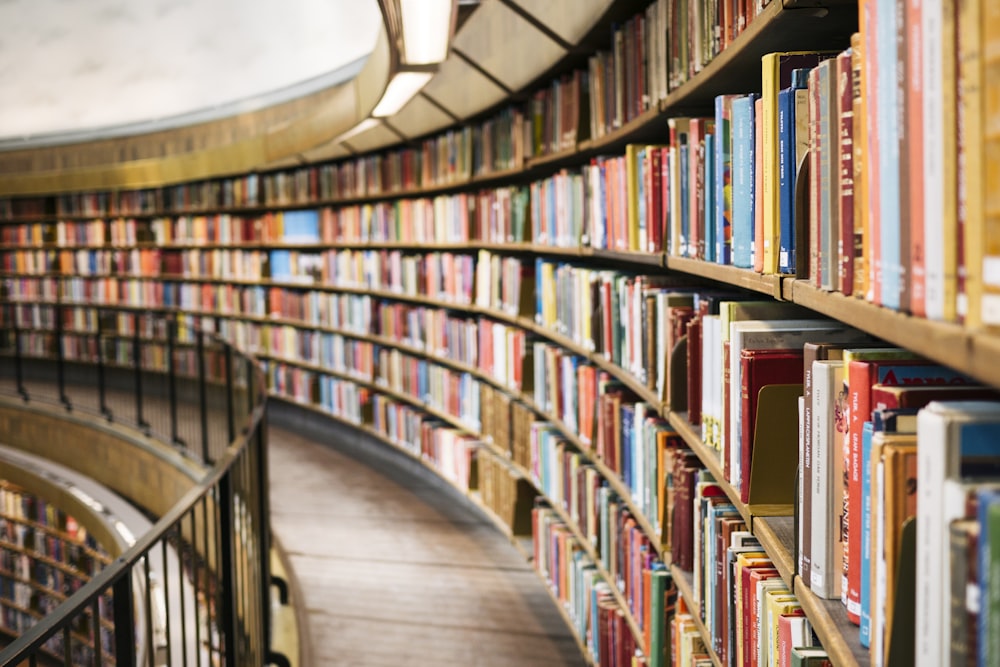

A little while ago, I saw photos of “The World 30 Most Beautiful Bookshops” making the rounds on Twitter. In particular, Boekhandel Dominicanen in The Netherlands stood out to me. Three floors of bookshelves sit under the vaulted stone archways of a medieval cathedral. It’s a beautiful image, and perfectly encapsulates an idea I’ve been thinking about a lot recently.

We venerate books, to the point that we treat them as nearly sacred objects.

We shouldn’t.

I understand the appeal. I get where the veneration comes from. In the 21st century, we are constantly reading — emails, text messages, tweets and documents. But as we’re inundated with headlines and notifications, books represent something else. A book on a shelf represents this staid, dignified repository of knowledge in an age when we are relentlessly harassed by information.

It’s no wonder that we build up the abstract idea of the book, even as the total value of book sales in Canada has fallen from $1.05 billion in 2014, to $894 million in 2020, according to Statistics Canada. According to BookNet Canada, only half of Canadians read or listen to a book at least once a week.

Nonetheless, in Canada we enthusiastically venerate not just books, but spaces for books.

Did you know The Weeknd filmed a music video in the Toronto Reference Library?

In the past decade, the Halifax Central Public Library and the Calgary Central Public Library both garnered national attention as new civic landmarks. Both buildings are architectural gems, and they represent a beautiful celebration of the idea of a repository of books.

But frankly, I’ve visited both buildings, and the books aren’t the main attraction. You can certainly find shelves full of books, but in the modern public library you’re just as likely to find 3D printers, podcasting studios, musical instruments to borrow, and freely available wifi.

I don’t mean this as a criticism; libraries should evolve with the times. But it’s striking to me how we venerate the idea of the printed word, and the aesthetic of books, even as we’re actually reading fewer and fewer of them.

In that same Twitter thread, Arc N Book in South Korea has a beautiful arched hallway with the spines of books extending to the ceiling overhead. It makes for an impressive photo, but of course all of those books must be glued in place or else they’d come crashing down. The books were destroyed to create a space that feels like it celebrates books.

All of this got me thinking about the strangest cathedral for books I ever visited, in a small town in Newfoundland and Labrador. I’m telling this story from memory many years later, so I might get some details wrong, but while I was working at the St. John’s Telegram in my 20s, an odd item appeared in the newspaper.

Years earlier, a used bookstore in town had gone out of business. The proprietor was a bit of a colourful character who lived in a small outport community called Pouch Cove, about a 30-minute drive north from St. John’s.

The man who owned the bookstore also owned an abandoned school in Pouch Cove. He was a painter, and had used the school building to host artists’ retreats. When his second-hand bookstore closed, he packed up the books and stored them in the old school until he could figure out what to do with them.

Years went by. The pile of books started growing. Apparently this is a weird phenomenon that happens sometimes. If word gets out that you have a very large pile of books, the pile of books tends to start growing. Because we treat books as these sacred objects, the idea of throwing books into the trash feels viscerally wrong.

But books can also be bulky and heavy, and cumbersome to store. So when a grandmother has to sell the house and move into long term care, or somebody is packing up and moving to Europe, maybe they don’t take all their books with them. Maybe you can unload some to the used bookstore in town, or give them away to friends, or donate the books to a charity.

But if all that fails, you certainly don’t want to just throw them away. These are books, after all. Maybe you hear that there’s a guy who already has a massive pile of books, so you give them to him. He’ll find a good home for them, right?

Eventually the situation in Pouch Cove became untenable. All that paper in an abandoned school was a fire hazard, and the owner was no closer to finding a solution.

So he contacted the local newspaper to announce his plan: For one summer only, anybody could come out to Pouch Cove and he’d unlock the old school and let you explore for as long as you wanted. Any book you wanted to buy, he’d sell for 25 cents. And then at the end of the summer, whatever was leftover, he was throwing it all into a bonfire.

Of course I made plans to visit immediately. Partly I was aghast at the idea of burning books, and partly I was excited to buy some reading material on the cheap. Also, it was also a killer idea for a date with a girl I liked.

When we arrived at the school and we were let in, the place was incredible. In room after room, the books were stacked nearly to the ceiling — sometimes on shelves and sometimes simply piled on the floor. They towered over you, like they were threatening to bury you in an avalanche of pages at any moment.

The atmosphere was gloomy and mysterious. There were no lights in the building, so you had to rely on the sunlight filtering in from windows. It felt like a secret treasure trove, and there must have been tens of thousands of books in the building.

But as we got to actually browsing the spines in those shadowy aisles between shelves, a deeper truth quickly became clear: the overwhelming majority of those books were simply not worth even 25 cents.

People have published a lot of utterly forgettable novels, and nonfiction about dated and esoteric topics.

(I have actually personally contributed to this oeuvre; if you want to read a humorous and informative account of the 2015 Newfoundland and Labrador election, you can buy Turmoil, As Usual on Amazon, but it’ll cost you more than 25 cents.)

Moving from room to room in the abandoned school, it quickly became clear that not much was worth taking, except maybe some of the classics. I bought a copy of Coriolanus by William Shakespeare, and one or two Hemmingway novels.

Over the course of the summer, I went back a couple more times, not so much because I wanted to buy books, but just because it was such a weird and enchanting space. I never checked back, but I assume at the end of the summer an awful lot of books wound up in the bonfire.

Here’s where all these thoughts lead: Ultimately, books are just a device to store and transmit data, with a long history and enormous cultural resonance. They’re only really as good as the substance of the words written on their pages.

I’ve been thinking about this a lot recently, because I bought an e-reader in March, and it has rekindled my love of reading. For whatever reason, in the past few years my ability to read books has dwindled. Some of it is the reasons that Johann Hari explores in Stolen Focus — a book that I didn’t read, but listened to in audiobook form.

Attention spans are short, distractions are rampant, and especially among 21st-century knowledge workers, we are living such intellectually stressful and exhausting lives, the idea of sitting and devoting hours of focus to reading a book for pleasure is a tall order.

In 2020 and 2021, I probably only read one or two books each year.

Since March of 2022, I’ve read eight books.

I know there are lots of readers who devour a lot more books than me. I’ve always been a slow reader, and I’ve never been the type of person to read a book in a single day.

What’s more meaningful to me than the number of books I’ve read, though, is the hours I’ve spent sitting quietly and reading.

Something about the e-reader has made it easier for me to read for hours at a time without wanting to pick up my phone and check my notifications.

And why shouldn’t there be innovative ways to improve reading? If a book is just a data storage and transmission device, why shouldn’t we use technology to improve upon an object that has remained largely unchanged for hundreds of years?

The e-reader is lighter than a book, which makes it more comfortable to hold, especially while laying down or in a hammock. The size and weight also makes it easier to throw in a bag to read on the subway, or on a patio while waiting to meet a friend.

It also has a soft backlight under the screen, which means you can read in a completely dark room, or outdoors at night.

But there’s also something that I struggle to put into words, when I try to describe how the e-reader just makes it easier to sit and read for long periods of time. The e-ink screen is much easier on the eyes than a laptop or phone screen, and with no notifications or built-in web browser, it’s hard to get distracted.

The text on the screen is larger than a typical paperback book, and the screen itself displays less text than a single page. As a result, the act of reading involves a lot more page-turning. It gives me a sense of momentum and progression, and I feel less likely to get lost and distracted reading the same paragraph over and over again.

On the flip side, there’s reason to believe that e-readers are significantly worse for information retention than a paper book. For me, though, after the past few years it feels like a choice between reading on an e-reader and not reading at all.

And I’m not sure how much it matters anyway. I would surely love to be able to read a book and remember every detail, but that may just not be possible for me. My brain is a product of a life lived online, and my memory sucks.

But there’s a lot to be said for reading a novel and letting the story flow into you at the pace of one page at a time. Reading nonfiction and letting ideas germinate as you think about a topic for a few hundred pages is a worthwhile endeavour.

It feels nourishing.

Since seeing that photo on Twitter of the bookstore inside a cathedral, I’ve been thinking a lot about books as almost a divine object, at the heart of a sort of secular religion of knowledge.

We display a bookshelf as our Zoom background as a little show of piety. We treat the printed word as sacred. We love books.

But it took an e-reader to remind me that the actual act of worship is found through sitting and reading for hours on end.

James McLeod is a Toronto-based writer. He works as a communications professional in the tech sector.

The Line is Canada’s last, best hope for irreverent commentary. We reject bullshit. We love lively writing. Please consider supporting us by subscribing. Follow us on Twitter, we guess, @the_lineca. Fight with us on Facebook. Pitch us something: lineeditor@protonmail.com.

We didn't have a lot of books growing up, but my folks, despite having limited education, loved books and encouraged us kids to read. What we did have, and revere, was our 80s-vintage "World Book Encyclopedia". Leather bound, gilt edges, yearly supplements, two-volume dictionary. Parents must have spent a fortune at that time. I inherited them, and kept them for a while. When I decided they weren't worth the space they occupied, I couldn't give them away. Sad. I think they went into the blue bin.

I also happen to have a set of children encyclopedias, from 100+ years ago. Those I'm keeping, not just because they belonged to my grandparents. They're a bit of a time-capsule. Even the smell. Now that I think about it that's a big part. The smell takes me back to childhood.

Great post guys, a nice read on a summer morning.

As someone who had the privilege of working at the Toronto Reference Library for twenty-five years my advice is to ignore this oblivious Philistine, not just because his notions about books and libraries and their respective roles check the half-baked, trite and obtuse boxes, but because it doesn't pay to heed people with no soul. To paraphrase Nietzsche slightly, every man repays careful study, but not every man is worth listening to.