Jen Gerson: If this is a war, where is the shared sacrifice? Where is the unity?

There should have been volunteer drives and crash training programs. Instead, we stayed home, baked bread and ate it alone.

When COVID-19 first emerged as a serious threat, I admit that I found myself in trouble. I'm a hack, a writer, a lowly pundit — the sort of person who makes a living by offering entertaining-but-contrarian little crumbs of political insight to the general public, and it’s worth every penny they paid for it. But when the virus came, I was stumped, and I wasn't the only one. A few of my fellow assholes-in-arms admitted to feeling the same ennui. In peacetime, its fine to fire potshots at the captains, but this was war. Most of us were at least subconsciously aware that our duties had changed — we now had an obligation to rally our people — and our writing suffered for it.

What I did bring myself to write in that moment holds up, I think. It can be read at Maclean's in its entirety, and I will leave the reader to judge.

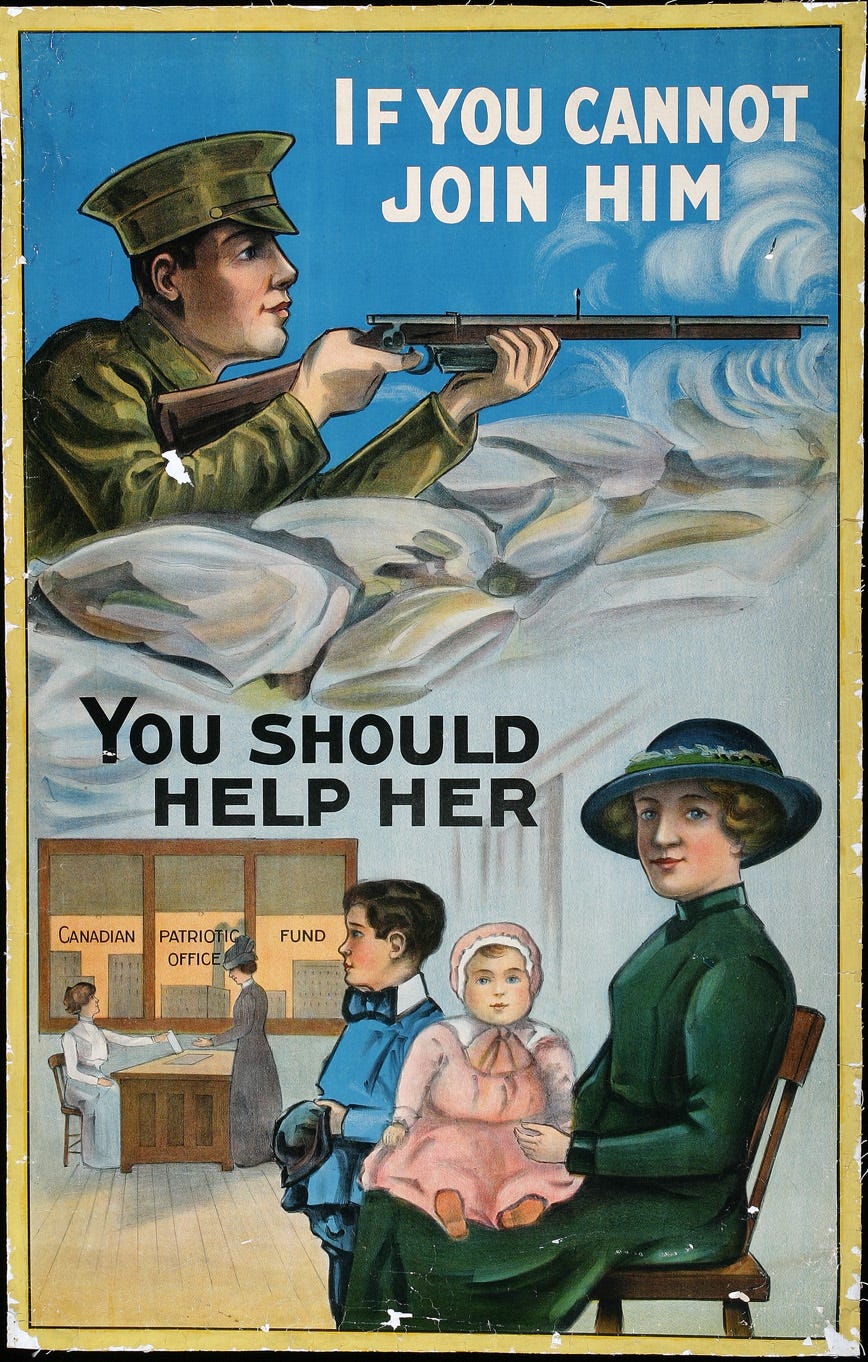

It was aptly titled: Yes, this is a war. Do our leaders know what that means?

"Did we spend the past two and a-half months building temporary hospital spaces? Did we conscript private companies to manufacture ventilators and personal protective equipment for health-care workers? … It’s still not too late to enlist useless lumps like myself to learn simple screening procedures to ease pressure on front-line medical workers in an emergency. Where is everyone? If this is a war, let’s act like it."

I wrote that column eight months ago, and that last question leaves me flummoxed still. Where is everyone? It's like the leaders who evoked memories of war had no earthly concept of what that entailed. I'm 36 years old, and while I've lived to see Canadian troops sent abroad in the service of blood, honour and treasure, I've served in no war. Unless you happen to be among the rare and dying generational cohort of my grandmother, you've probably served in no war, either. The very notion of a true total war is foreign to most of us. It's a fantasy of heroism: a Spielberg movie, a contender for best picture we can take in while wearing silk blouses and fattening ourselves on chocolate and popcorn.

A war, a pandemic, a true generational crisis — this requires more of us than simply acquiring masks and gowns and keeping our distance at the pub. To make the analogy apt, the moment demanded that we temporarily sublimate our individual needs in the pursuit of the collective good. We needed to assume a fleeting collective identity, a shared purpose in pursuit of a higher, more sacred goal.

That is the true test of leadership in a crisis. It's not about putting a politician in front of a television to tell us what to do. What we needed were rituals of unity; physical acts of collective sacrifice to give us the sense that we really were all in this together.

There should have been mass volunteer drives. I know of a few drives to create homemade masks and PPE — but only a few. We could have baked goods for health-care workers and ailing neighbours.

There was some of this, of course. I saw some bright artwork on windows in the pandemic’s early days. Better women than me worked tirelessly in foodbanks and the like, I’m sure.

I had some hope that we would see more when many cities began nightly cheering sessions for health-care workers.

And then, one day, the cheering just stopped.

In Alberta, I never heard it at all.

I am not sure that the most inspired leadership could have made those cheers ring on indefinitely — but what we have received to date at all levels has not met the challenge at hand. Oftentimes, our leaders have been remote, tone deaf, and even hypocritical. At the federal level, we have a Liberal faction that seems to be more focussed on using this historic crisis and setback as an opportunity to push their pet ideological projects on an exhausted public. The various provincial leaders have, at times, vacillated between too-stringent restrictions on benign behaviours, to placing too high a priority on the needs of businesses.

We've received financial support, certainly — a $380 billion deficit will attest to that — although I can't help but observe that the compassion for the gig-worker has not been extended to the small business owner.

Government communications about even the most basic public-health advice has been an abject failure. Early dithering on mask advice, for example, planted a seed of distrust that is now creeping its way into anti-masking protests around the country.

There's been no vision. No understanding that while the crisis we face is certainly financial, money alone cannot fix it.

Worst of all has been the knowledge that the best thing that most of us could do in response to this pandemic is nothing. Where war offers us the possibility of a holy sacrifice in the service of duty, instead, what this crisis brings us is isolation and idleness. Almost as if it were hand-crafted to test the spirit of an already demoralized and atomized populace.

War is horror. And yet, many of those who survived the First and Second World Wars remembered that time, paradoxically, as some of the best of their lives. For a few years, individual impulse was replaced by a higher meaning, a sense of purpose that many would struggle to articulate in the moment, and recall with painful nostalgia once it was gone. We still romanticize the horrorshow of that era; the power of that moment in time lives with us, even among those too young to remember and too unschooled to name it.

That's also what's made COVID-19 so impossible. It's denied most of us the rituals of collective action and self sacrifice that would have allowed us to find meaning in loss and suffering.

Instead, we're back at home, alone, doing nothing, baking bread for nobody but ourselves.

A friend I have not been able to visit in months posted the following quote from Pope Francis to his Facebook wall.

"We should recognize how in a culture where each person wants to be bearer of his or her own subjective truth, it becomes difficult for citizens to devise a common plan which transcends individual gain and personal ambitions."

I'm in the midst of reading The Righteous Mind by Jonathan Haidt, and I wish I had read it sooner. If you haven't yet, pick it up immediately. It articulates one of the central problems of atheism as I practice it, and it tackles a doubt that I have struggled with now for years. Secular atheism may be technically correct, but it's also inadequate. Humans are meaning-seeking meat machines evolved to live in small groups that share a common purpose.

In healthy liberal democracies, that impulse is channeled into a vibrant civic society; we share the daily struggles of our co-workers; the competitive spirit of our bowling leagues; the altruism of our volunteer commitments; the sorrows of our supper parties, and yes, transcendence within our spiritual communities. Without these, we unhinge.

An individual alone is a mote on the wind. Isolated. Defenceless. Desperate to reconstruct tribal bonds in any way available to him. Even a man who is materially comfortable will find himself deeply vulnerable to demagoguery, conspiracy theory, hatred, and other expressions of political madness if he cannot find more constructive outlets for unmet human needs.

One of the first goals of a truly authoritarian political movement is to destroy, expel, or co-opt every element of civic society. To turn our spiritual needs for meaning and connection make them subservient to the only acceptable political end.

John Adams offered this famous quote about the nature of the people required to operate a democratic republic: "Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other."

Atheists balk at this quote, but I think we can interpret the word "religious" rather broadly, here.

I think about these things when I read Ken Boessenkool's piece this week at The Line, in which he notes that the populists in the Conservative tent have gone a little nuts.

I come back to these thoughts when I see stories about an Edmonton bar server getting slashed in the face over a mask by-law fight.

When I see this emotional appeal from Brian Pallister and think it's the first bit of humanity I've seen from any elected leader in months.

Or when I imagine the shape of the partisan worm eating the brain of someone so morally progressive that he argues for letting fellow Canadians die because of the failures of the people who lead them.

There are a few heroes of this war: health-care workers, certainly. Also, the researchers whose timely vaccine has put an end in sight.

To the rest of us, however, I can't help but feel that we've been subject to a terrible test — and been found wanting.

The Line is Canada’s last, best hope for irreverent commentary. We reject bullshit. We love lively writing. Please consider supporting us by subscribing. Follow us on Twitter @the_lineca. Fight with us on Facebook. Pitch us something: lineeditor@protonmail.com

There have been some really good articles in the past, but this one hit home and caused me to hit “subscribe”. Looking forward to the future posts!

Great piece, Jen.