Joshua Hind: The NDP always has the most popular leader. But they don't win elections

TikTok is likely very necessary to reach young voters, but the party has to ask itself if having a well-liked leader is the most important thing.

By: Joshua Hind

Only the most die-hard supporters of the New Democratic Party thought the recently-concluded 2021 federal election was winnable in the way 2015 felt very winnable in the early days. Still, the NDP’s showing at the polls — a single-digit increase in popular vote and a single new seat — is undeniably disappointing for a party that spent big to win back seats.

With that disappointment gnawing at them, the NDP and its faithful are bound to want to assign some blame, a process which always starts with the leader. But that’s a uniquely tough proposition for the NDP, who not only has Canada’s Best-Liked Leader™ in Jagmeet Singh, but has also positioned Singh to be the entire personality and profile of the party. In trying to create another singular figure like Jack Layton, the NDP has painted itself into a tight corner.

In project management there’s an old joke about the “Six Phases.” Like the stages of grief, the six phases of project management are the various emotional states into which all large projects — construction, software development, political campaigns — can be divided. They are: enthusiasm, disillusionment, panic, the search for the guilty, the punishment of the innocent, and the promotion of the uninvolved.

It’s easy to see the first three in an election, where enthusiasm, disillusionment and panic often happen all at once. Now in the post-election period, parties must wade into the more fraught final phases.

The search for the guilty started the moment the networks called the election for Justin Trudeau’s Liberal Party, and Conservative leader Erin O’Toole is already under scrutiny. The Greens, for their part, got a head start on punishing the innocent by pinning their party’s staggering immolation exclusively on their (now former) leader, Annamie Paul.

For the NDP, things are more delicate.

Jagmeet Singh, who’s personable, well-spoken and very photogenic, was front and centre in every aspect of the NDP’s campaign. Their bus exclusively featured his name and picture, the first page on their website is simply labelled, “Jagmeet”, and every campaign stop was focused on the leader and his appeal. But the “leader first” tactic that arguably got the most attention was the social media campaign, specifically Singh’s appeal to young voters through TikTok.

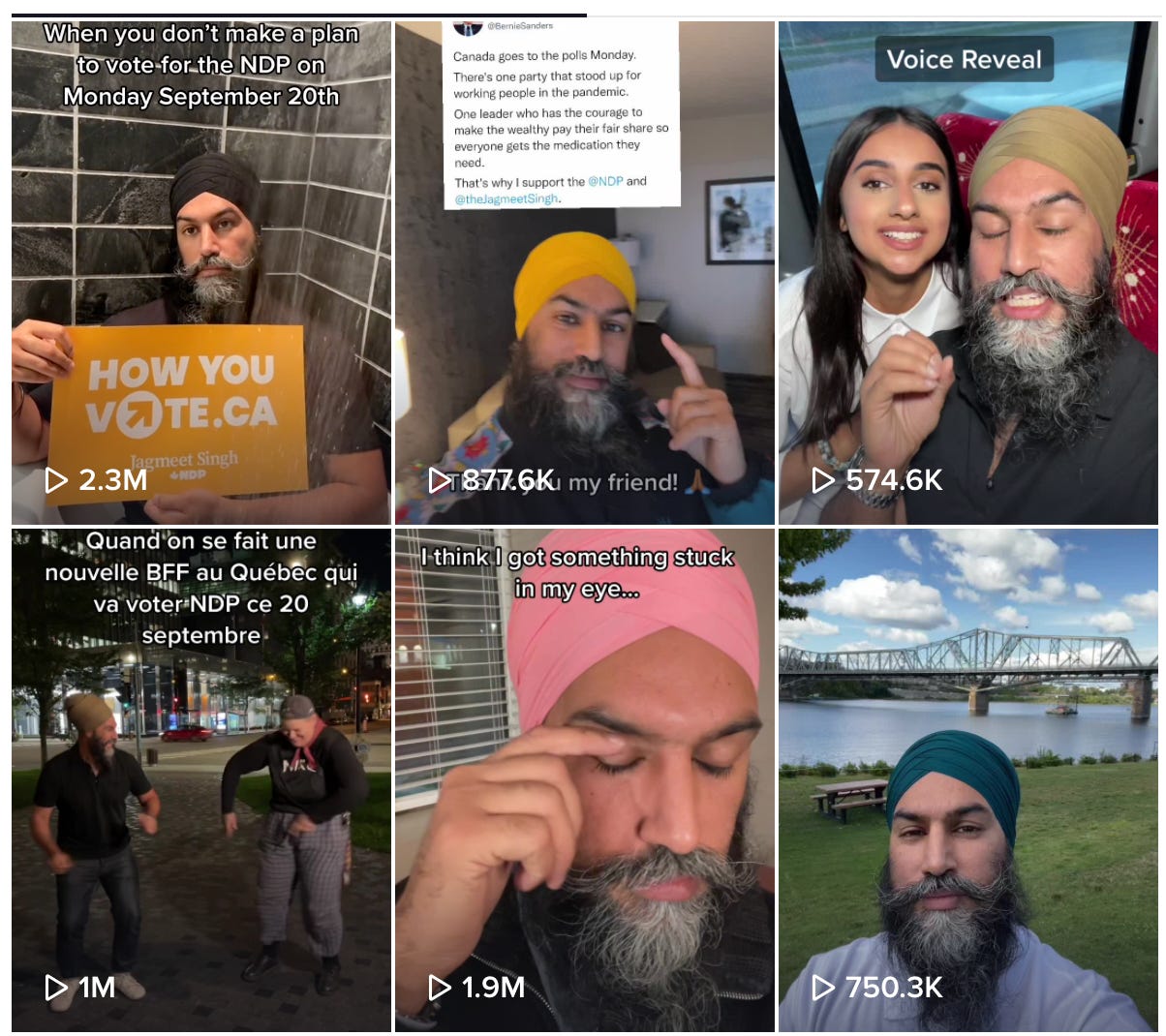

Singh is the undisputed Canadian political TikTok champion, with nearly 850,000 followers and videos that regularly rack up millions of likes. His content is charming and apparently quite credible with TikTok users, at times fun, mischievous and pleasantly silly. It’s also clearly the platform Singh likes best. His Instagram account is mostly reposts from Twitter, and his Twitter account, while popular, doesn’t get nearly the response he earns on TikTok. Because it’s so important to Singh, and presumably the NDP, it can also form the basis for appraisals of both, and that creates new challenges.

Don’t misunderstand, the activity on TikTok and other social media is interesting and likely very necessary to reach certain cohorts of voters, especially the young ones, but the NDP has to ask itself if having a well-liked leader is what matters most, and what achieving that distinction does to other aspects of Singh’s credibility. How can the NDP, as a whole party, become as well-liked as their leader while establishing him as a sound choice to guide us through what are sure to be tough years ahead?

Young voters are very important to the NDP and that’s a good thing. There has to be a party which is not only interested in them, but values them and their worldview. But growing the party’s seat count also demands the inclusion of older groups of voters. Those NDP supporters who were young and coveted during the Orange Wave of 2011 are older now, communicate through older means (dusty Twitter and Facebook, for example) and have different needs and interests, committed as they still may be to progressive causes. What’s the plan for them?

The other risk of focusing so much on using a single social media platform to reach a specific cohort of voters is that other voters won’t understand the appeal. Of all the videos Jagmeet Singh produced during the campaign, it’s the ones in which he’s dancing, lip-syncing, or sitting under shower that get millions of responses. The so-called “emotional shower” video went viral and got 2.3 million likes. An earlier, more conventional video in which Singh explains why he’s running got a mere 300,000 likes.

And social media meme campaigning isn't just a potential turn-off for older or more disconnected voters because they don't understand it. Those voters are less interested in being courted and more interested in hearing hard policy ideas. Since the “Liberal Light” turn under Thomas Mulcair in 2015, older, longtime NDP voters (myself among them) have been begging the party to get serious about creating hard-left policy. Instead the 2021 version of the NDP gives them means-testing and memes.

One assumes NDP data is telling them they have to use social media to get their message out (or they’re using the data to justify a preferred approach). And no one is suggesting the party abandon young voters. Again, they’re important to the party and deserve to treated as such, but it does their very, very popular leader a disservice to have to play a clown in new media and then have to turn around and sell himself in legacy media as a credible leader for difficult times.

There’s a possible solution which also speaks to one of the grumbles currently circulating among NDP candidates and supporters alike: make it about the party, not just the leader, and give the candidates greater profile. If TikTok (or whatever platform follows it) is working with a certain cohort, go for it. But it doesn’t always have to be the leader clowning around. Surely there are candidates with great personalities and ideas who could do more of that.

When speaking with NDP supporters, the goal for many of them is to build a movement, which is inarguably vital when proposing the kind of progressive social programs that are (or should be) the cornerstone of the NDP platform. Movements might coalesce around a single person, but they don’t succeed on solo effort. The NDP had 338 voices (or 336 or so by the end of the campaign, but that’ll happen) and it chose to focus on one. That’s not the start of a social democratic movement, that’s the foundation for a cult of personality.

Being well-liked is a trait most NDP leaders share, federally and provincially. From Ed Broadbent to Jagmeet Singh, the NDP has had the most popular federal leader for decades and it's never mattered at the ballot box. There is no magical leader who can do it singlehandedly. And indeed there are parts of this country where the leader might not be able to do it at all. Popular movements don’t mean a movement with one popular guy. It’s time to spread the work around.

Joshua Hind is a designer, project manager and writer based in Toronto. Follow Joshua on Twitter at @joshuahind.

The Line is Canada’s last, best hope for irreverent commentary. We reject bullshit. We love lively writing. Please consider supporting us by subscribing. Follow us on Twitter @the_lineca. Fight with us on Facebook. Pitch us something: lineeditor@protonmail.com

Now that Trudeau's won three elections in a row (one majority and two minorities), maybe it isn't too early to contemplate Trudeau's effect on the Conservatives and NDP. After the Harperite position (small government and low taxes, no action on climate) was rejected by voters in Ontario in 2015 and again in 2019, O'Toole made a sudden lunge for the centre, surprising the Liberals in the first weeks of the campaign. In the end he did raise the Conservative vote share in Ontario and Quebec, although not enough to win more seats. The Conservatives will have to decide whether to keep O'Toole and stick to his "Liberal lite" strategy, or revert to Harper's hard-right stance. http://induecourse.ca/lessons-for-the-left-from-olivia-chows-faltering-campaign/

What about the NDP? Comparing the 2015 campaign to the 2021 campaign, or provincial NDP governments to the federal NDP, there's always been a direct relationship between the NDP's proximity to power and the realism of its policies. On top of that, under Trudeau, the Liberals have moved towards the progressive side (Canada Child Benefit, higher taxes on the top 1%, CPP expansion, nationwide carbon pricing, legalizing marijuana, funding and attention for Indigenous issues, generous income supports during Covid, national $10/day childcare), and the federal NDP has had to take even more progressive (and arguably unrealistic) positions to differentiate themselves: a wealth tax on billionaires, universal basic income, shutting down oil and gas production (Avi Lewis and Anjali Appadurai).

I think the NDP's strongest pitch to progressive voters is that the Liberals aren't ideologically committed, the way that the NDP is. At the provincial level, with a two-party system, it's clear that the NDP can win elections in Saskatchewan, Manitoba, BC (sometimes), and Alberta (at least once). At the national level, though, holding the country together against strong regional tensions is a major part of governing, and I would argue that the Liberal Party's ideological flexibility and willingness to compromise (carbon pricing *and* pipelines!) is an advantage compared to the NDP's ideological commitment.

More than 100 years ago, the French scholar Andre Siegfried commented on the shapelessness of Canada's national political parties: because of Canada's fragility, Canadian politicians sought to avoid emphasizing social divisions. Ken Carty:

"Political parties had emerged in the nineteenth century with the development of representative democracies. ... in order for parties to be effective they had to stand for something - distinctive ideas, recognizable interests - so that electoral competition between them would offer voters meaningful choices. Thus, in most democratic societies, parties usually appeared to reflect the prevailing lines of social and economic division: labour parties, Catholic parties, bourgeois parties, farmers' parties, linguistic parties, regional parties all ordered political debate and structured electoral competition. To Siegfried's surprise, Canadian parties rejected any such 'natural form'....

"... He argued that they had developed their unnatural form because the country's politicians recognized that, as a country, Canada was so inherently fragile that its continuing political existence was at stake. The 'violent oppositions' that existed between French and English, Protestant and Catholic, centre and periphery all threatened to pull the country apart, and so national party politicians actively worked to prevent the formation of parties that would represent their individual and distinctive claims. For Canadian politicians there could be no appeal to natural constituencies for fear such parties would threaten the stability and very existence of the country (as the emergence of the Parti Quebecois and the Bloc Quebecois seventy years later would prove). Instead, Canadian parties were induced to reject appeals to definitive principles, or specific interests, and were reduced to seeking electoral support wherever, and from whomever, it might be found. The result was an unnatural form of electoral competition in which parties were forced to exist as 'big tents' - shapeless, heterogeneous coalitions based on continual and shifting compromise."

How old is this writer? He sounds like one of those cantankerous old men griping about "kids and their technology" these days. Yes Mr. Hind, the leader does in fact need to be likeable - and somewhat relatable - and Mr. Singh is the only leader who is both. The other two were (and are) like stale relics that smell musty. Their ideas are old, at least one of them is smarmy and arrogant and the other tries to fake it til he makes it. They are not at all likeable and it does actually matter. I would also have to wonder what the objection is to making it all about Mr. Singh? Perhaps - just maybe - some of the NDP candidates didn't come off so well. Edmonton elected a new NDP candidate - in a previous conservative hardcore stronghold held by Diotte (who has a long history in the city FYI). The Candidate busted his chops, had great social media engagement, worked really hard to get himself out there and succeeded.

In addition, did it ever occur to the writer that the way things are done has *insert gasp* changed? The old ways of campaigning might appeal to the over 50 crowd but some of the rest of us like to see campaigns and party platform reveals or interaction with the leader of the party that uses new ways and new technology because it indicates a willingness to innovate and pivot and do what is necessary to reach a cohort. It isn't about social media, it is about using whatever is available to reach the largest cohort possible and meet them on THEIR playing field. The other two parties were deeply negligent in this.

The Liberals didn't have a single fresh idea in their platform and as much as they like to think that everyone loves Trudeau, some of us only voted Liberal because we can't stomach the Conservatives (particularly who fits in their "big blue tent"). The Conservatives had some nice ideas but their platform engagement was absolutely terrible and they still have a number of highly highly problematic MPs that make O'Toole's words about being a more welcoming inclusive party a bald faced lie (looking at Michael Cooper directly) Whomever was running their social media comms should be fired and banished from any comms ever again. The twitter ads in particular were absolutely ridiculous. They looked mean and petty. Both parties should be ridiculed for their social media campaigns actually.

This article sounds like one long gripe that the younger generation got more attention but is cloaked in ideas to help the party. It also sounds like sour grapes.