Lyman Stone: Why aren't women having more babies? We should ask them

Canada has shockingly little available information about women and their fertility choices. Because we don't ask for it.

By: Lyman Stone

The last time researchers asked Canadian women about their unintended pregnancies was in 2006, and before that in 2002. You might not realize it’s been almost a generation go since Canadian authorities could be bothered to ask women about their fertility. The Toronto Star, for example, claims that a “2015 study” shows high rates of unplanned pregnancy, but that study cites a 2009 study, which in turn cites a survey in, you guessed it, 2006. And that survey was done using a private market research panel, not official government statistical agencies. Since then, there have been no published or documented surveys on the topic (though the 2017 General Social Survey asked some related questions, discussed below). Evidently, for the last 15 or 20 years, what women want in terms of their childbearing has not been a top-tier item of interest. And indeed, Canada’s ongoing challenges with forced sterilization of Indigenous women suggests that, for many authorities working on these issues, “what women want” is hardly a consideration at all.

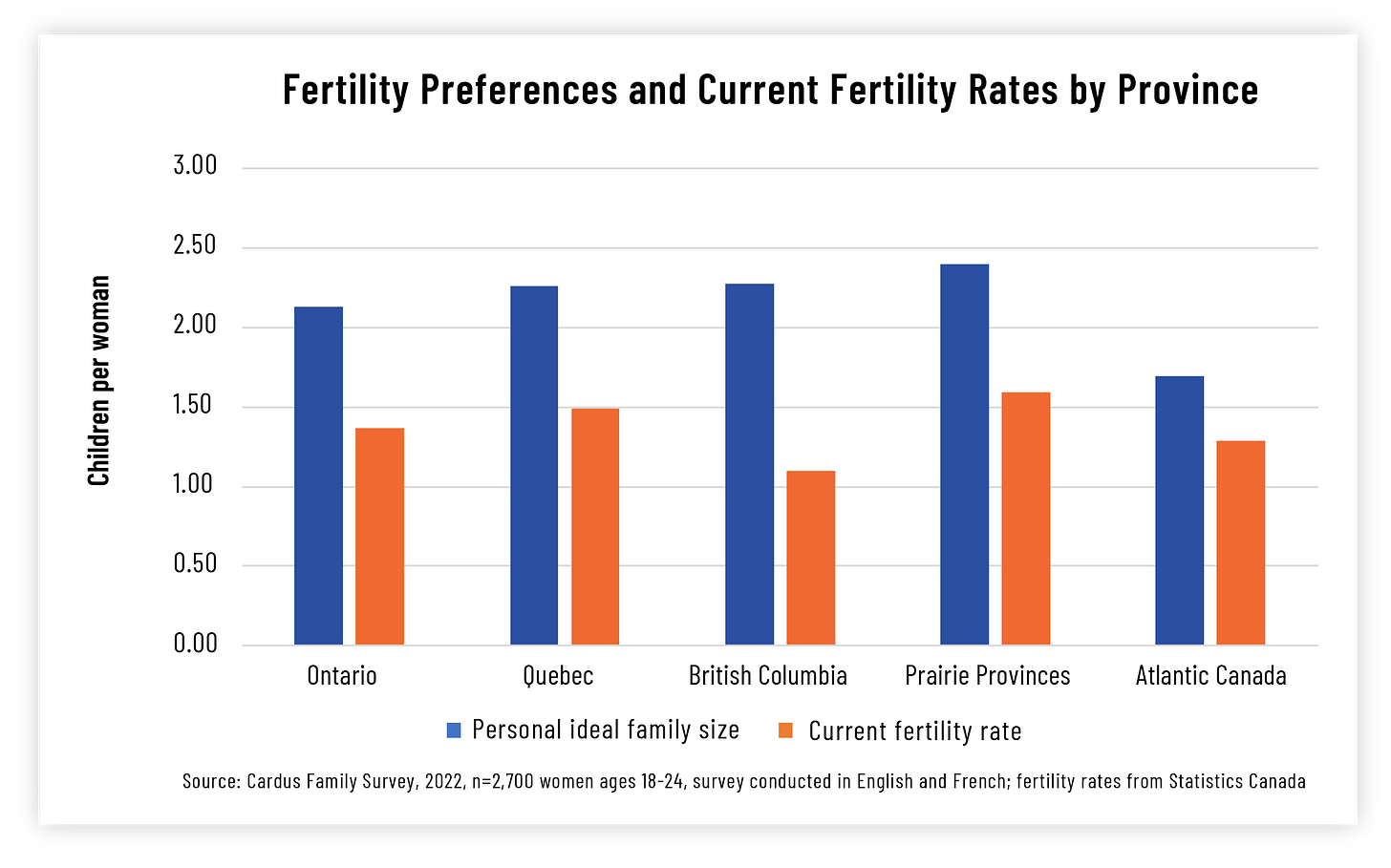

It was precisely because Canadian policies around family and fertility seemed so devoid of any reference to what women actually wanted for themselves that I conducted a survey of women’s fertility preferences last year with public policy think tank Cardus. What we found was striking, and shown in the figure below.

On average, Canadian women report wanting to have about 2.2 children. This was true for two different question wordings we tested. Even when we asked women to consider barriers in their life and tell us just how many children they actually intended to have, the answer was around 1.9. And yet, Canada’s current fertility rate is just 1.4 children per woman.

There are regional variations. In the Atlantic provinces, women can expect to have just 1.3 children on average; but since they report desiring just 1.7, the gap between desires and likely outcomes is fairly small, around 0.4 children per woman. On the other hand, in British Columbia, women can expect to have just 1.1 children on average, despite the fact that they report desiring almost 2.3 children. British Columbia has the largest gap between women’s stated desires and their likely outcomes from current birth rates of any province.

And yet British Columbia is leading the way providing free contraceptives. To be clear, I share the desire for women to have reasonable access to contraception. After all, our own survey showed that women who have excess, undesired births, although a small proportion of Canadian women, have much lower life satisfaction than other women. Avoiding this kind of adverse outcome is obviously very important to women and increasing access to birth control is an appropriate policy response to that real problem.

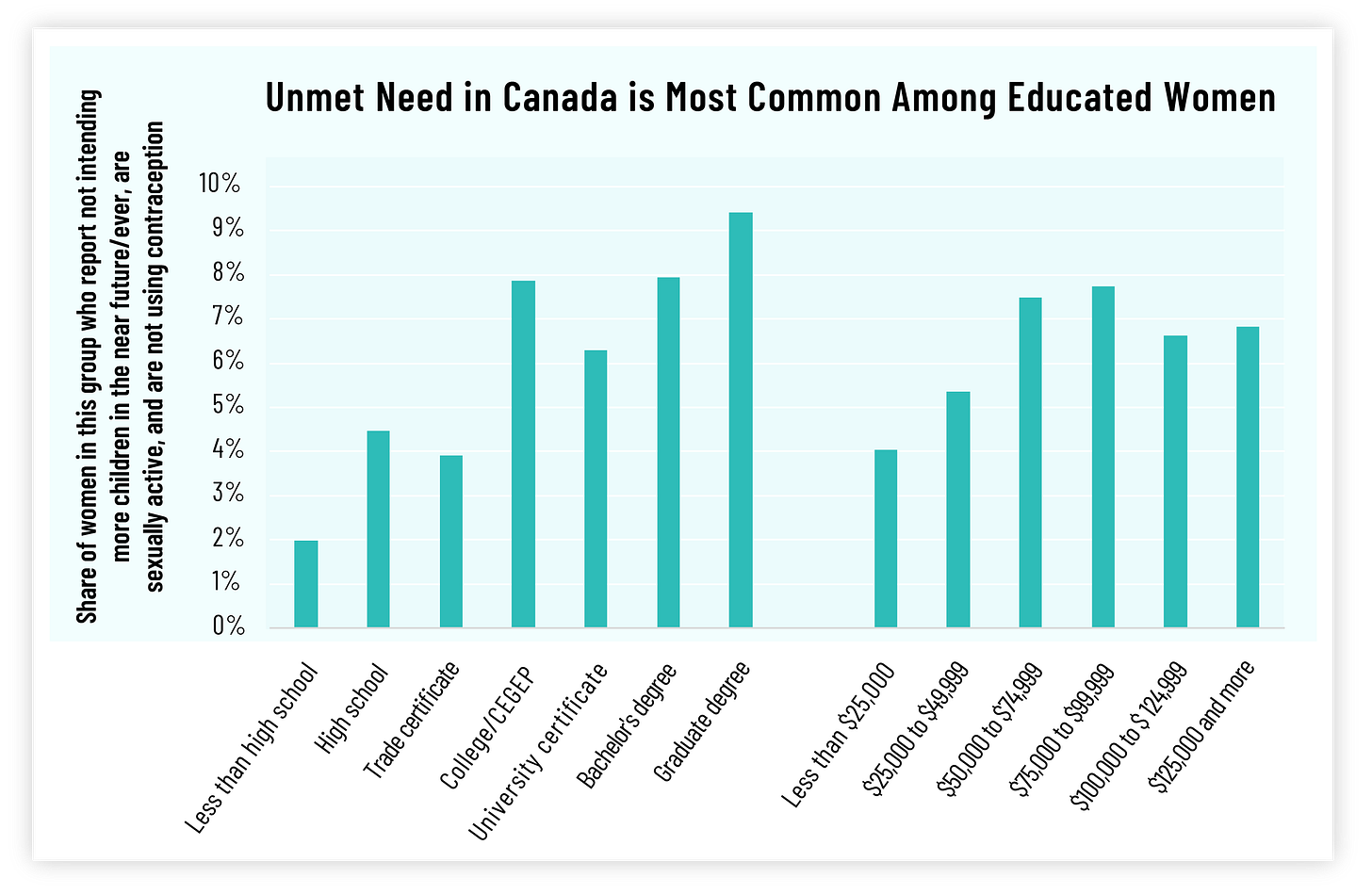

The point is, however, that Canadian women are already quite successful at avoiding these undesired outcomes, not least because the Canadian health-care system already makes contraception pretty widely available. According to the latest international estimates of “unmet need for contraception,” Canada has one of the highest rates of contraceptive coverage in the world, higher even than is average for high-income countries. We are higher than Germany, Sweden, Spain or Italy. And when the 2017 Canadian General Social Survey asked women about their future fertility intentions and current contraceptive use, only seven per cent of reproductive-age women reported unmet need for contraception. In British Columbia the rate was slightly lower, at six per cent. And in the General Social Survey, it’s not at all random who has unmet need (i.e. wants to avoid pregnancy, is sexually active, but isn’t using contraceptives): it’s higher-income, better-educated women. The figure below shows unmet need from the General Social Survey as a share of reproductive-age women, by their educational and income levels.

“Unmet need” in Canada is not mostly a problem of poorer, less educated, younger or racialized women having insufficient access to contraception. Statistically speaking, it’s mostly a product of higher-income, better-educated women who do not use contraception for a wide variety of reasons, even though they can in principle access it. This is a phenomenon demographers call “demand-side unmet need,” and it basically means women who in principle might have “unmet need” for contraception, but who in practice do not use contraception for other reasons (for example, they might have religious objections).

This is not how most people envision “unmet need,” but it actually turns out to have a global implication as well: the latest global estimates of unintended pregnancies show that pregnancies in Sub-Saharan Africa and Europe have the same likelihood of being “unintended.” Countries with widespread contraceptive usage do have lower birth rates, but the share of pregnancies which are unintended is just about the same everywhere in the world, regardless of contraceptive usage. Even when supply of contraception is high, it turns out demand for children often falls about proportionately, such that the overall share of children who are “unintended” (i.e. not “demanded”) doesn’t really change much.

The sudden trend among Canadian authorities to make contraceptives free reflects a real interest in promoting women’s wellbeing, but an embarrassingly narrow focus on just one small slice of that wellbeing. That narrow focus rests on an extremely thin evidentiary base alongside a feckless disregard of such evidence as does exist. Put bluntly, there is no evidence that British Columbia reducing the patient payment for birth control from $5-$50 per month to $0 will in fact prevent any unintended pregnancies, since unmet need for contraception is not primarily driven by low-income women with budget constraints, and around the world we do not in fact observe a correlation between contraceptive prevalence and lower likelihood that a given pregnancy is unintended.

If Canadian policymakers want to help women with their reproductive goals, $40 million a year is a fairly paltry sum, but it would be plenty for Canada to start fielding a regular survey of women’s family desires similar to the global Demographic and Health Surveys or the U.S.’s National Survey of Family Growth. Better information is the first step to making more sound, evidence-based policies.

Beyond this, while preventing unintended pregnancies is important, policymakers should think about what they can do to help women achieve their desired childbearing, a far more prevalent concern. British Columbia in particular is a place where women are uniquely likely to fall short of their fertility desires, not overshoot them.

The lawmakers in Victoria might want to consider why British Columbian women experience such dramatic restrictions on their reproductive freedom that they are unable to have even half as many children as they report desiring; bothering to ask those women about their lives would be a good first step.

Lyman Stone is a Cardus senior fellow and a demographer specializing in fertility and family.

The Line is Canada’s last, best hope for irreverent commentary. We reject bullshit. We love lively writing. Please consider supporting us by subscribing. Follow us on Twitter @the_lineca. Fight with us on Facebook. Pitch us something: lineeditor@protonmail.com