Mitch Heimpel: Our parties are afraid of their own activists

Liz Truss. Donald Trump. The B.C. NDP. All of them seem to be afraid of their own voters.

By: Mitch Heimpel

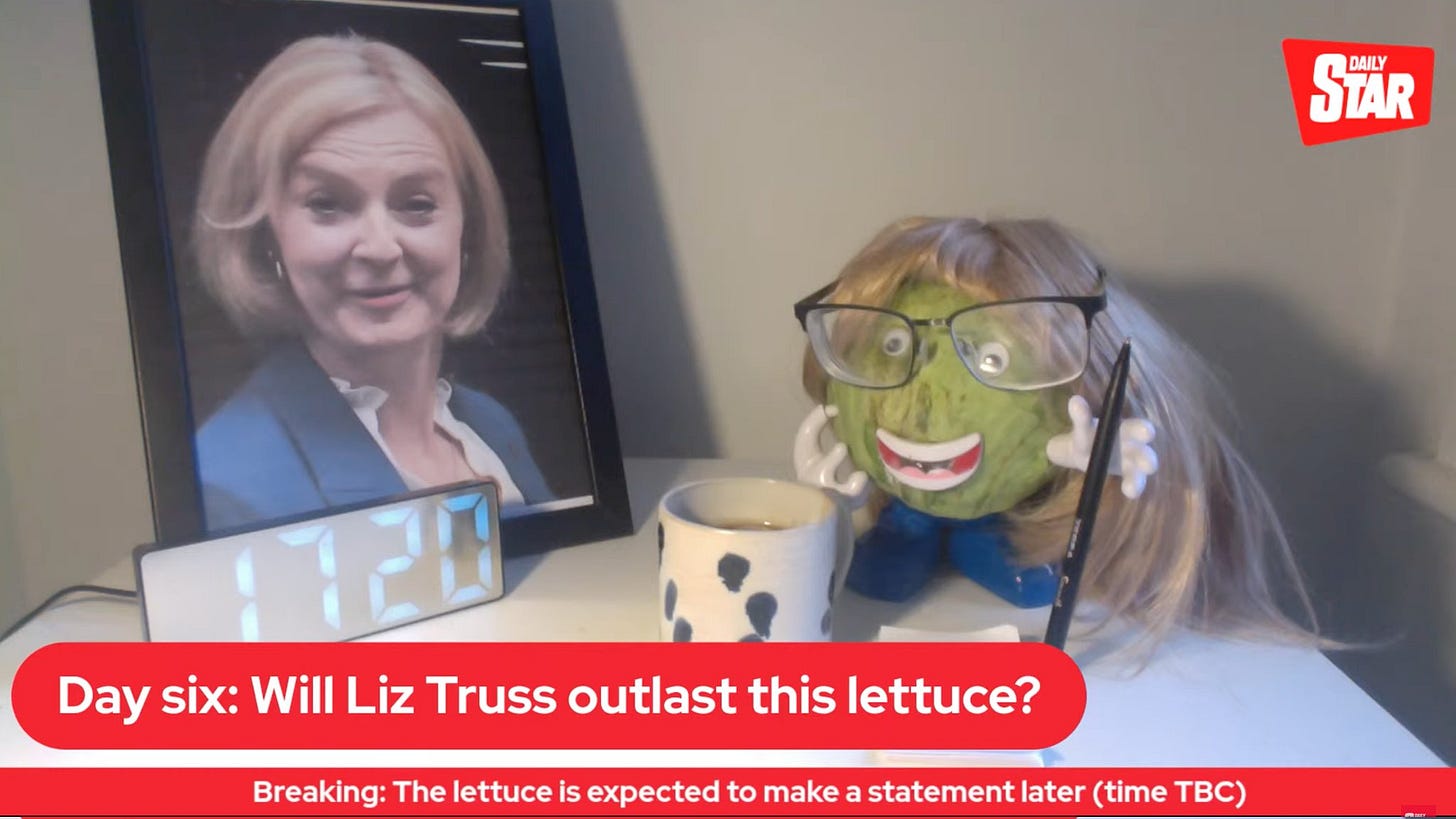

In the end, the lettuce won.

You may have already forgotten, but for a while last month, a wilting head of lettuce was making global news. A British tabloid, watching the wildfire eating the Liz Truss government, began livestreaming the produce as it sat in the open air atop a counter, wondering whether the lettuce would rot before Truss was purged or quit.

The smart money was always on the lettuce. From the moment the Pound tanked, and the Bank of England had to launch back into a massive round of quantitative easing to calm the bond market, any other result was out the window.

In the weeks since, and especially since the recent midterm results in the United States, I've been thinking about that damned head of lettuce, and what it says about politics in the West today (or at least in parts of it!).

Let's take the U.K. first. Truss was, barely, the third choice of her own party. It took five rounds of voting for Truss to even get into second place among Conservative MPs. She almost finished fourth on the first ballot. Unlike Boris Johnson, or Theresa May, or David Cameron, her own colleagues had doubts from the outset that she was up to the job. The Tories had watched a similar act take place across the House for years as Jeremy Corbyn, the former Labour leader, could never command the loyalty of his caucus. They — in an astute assessment of character and talent that is totally unlike the Labour Party — believed Corbyn unfit to do the job, unable to win an election, and a talentless albatross foisted upon them by an angry and polarized electorate. They were eventually vindicated when the electorate handed Labour their worst defeat since 1983 at the hands of Boris Johnson.

And this brings me to my point. Our political parties are now afraid of their own activists.

This is not only true in the U.K. George Will famously said of the Republican Party under Donald Trump, "... the Republican Party is in a very peculiar position. A large number of its elected officials are terrified of their voters ... And if you’re afraid of your voters, you don’t really respect your voters. And if you don’t respect them, you don’t really like them." The recent midterm results in the United States speak to this. The expected Republican red wave never materialized. As of right now, with a double-fistful of districts still up in the air, the G.O.P. will likely, but not certainly, retake the House of Representatives by a few seats. But the Democrats held the Senate and performed well in state-level races. President Joe Biden no doubt would have loved another dozen House seats, but he did far, far better than both the polls and historical precedent would have suggested.

Though it's a bit early to make a definitive call on what short circuited the red wave, the ongoing split in the Republican Party is an early suspect. In Florida, Governor Ron DeSantis, widely considered the most likely man to lead the party who is not named Donald Trump, had a fantastic evening, romping to an easy victory. Meanwhile, the candidates Trump backed, and those most closely aligned with his big lie of a stolen 2020 election, performed poorly. Objectively speaking, the Republicans have all the evidence they need that Trumpism is an electoral dead-end. After a fluke win against a weak Democrat in 2016, Trump has lost consistently since.

But the party hasn't moved on — it's talking about moving on now, but it's way, way too soon to tell if they actually mean it this time.

Why the delay? Why the doubt? Why the hesitation? Because the G.O.P. brass know full well that a significant portion of their base is more loyal to Trump than to the party or conservative ideology generally. They also suspect (as everyone paying attention must) that Trump himself will not hesitate to wage total war against DeSantis or anyone else who stands between Trump's bruised ego and a shot at electoral redemption. The rational choice is clear: the Republicans should drop Trump, and should have years ago. But they haven't, and still may not.

Because they're afraid of their own activists. They’re afraid what happens if their own base turns against them.

We see versions of this here, too, and it takes on a slightly different flavour in Canada (or other Westminster countries) because our systems are different from the American one. For a local example, we need look no further than the province of British Columbia to see politicians fearful of their own base. During their recent leadership race, the B.C. NDP disqualified Anjali Appadurai from running against then-attorney general David Eby. Eby, now premier-designate as John Horgan prepares to exit public life due to poor health, had been endorsed by nearly the entirety of the B.C. NDP caucus. He has long experience as a senior minister in Horgan's government. It's pretty clear that, simply by virtue of no other cabinet minister running against him, the New Democrats thought they could stitch up a neat and orderly succession.

Appadurai meant to challenge that. She went out and sold memberships. Most B.C. political watchers believe she likely well out-sold Eby. They also believed that the party would force her from the contest. They did just that, under a charge that Appadurai had conspired with a third-party organization to sell memberships, and that the third-party organization she conspired with then proceeded to do so under shady circumstances.

Eby owned the elected class. Appadurai had the activists. In the end, those with the power tilted the table. But not before well-known federal New Democrats, like Niki Ashton, who proudly place themselves on the party's activist wing, took to Twitter to decry Appadurai's ejection.

That's just a recent example — I could rattle off a few more versions of this in Canada, but that would be belabouring the point. Here's the bottom line: we have presidentialized a system that doesn't elect a president. Prime ministers and premiers are meant to be the leaders of the party that elects the most members to a parliament. The members they are elected with are, by the very design of the system, meant to have a significant say over who will be the leader. That we are, now, having the same problem as an actual presidential system means that we have dismantled safeguards that are there intentionally to ensure good government — we are giving the activists the power that so terrifies the politicians.

In any Westminster system, you will always have conflict if you have a party leader who is hired by the membership but can be fired by the caucus. These two groups are not the same, and a big part of the difference is that elected members of Parliament and provincial legislatures are forced to deal with the realities of governing. Their activists, while they may live with the results of those decisions, are often freed from having to consider the public-policy tradeoffs. They have the luxury of believing that there is an ideological solution to everything. Liz Truss just ran into a buzzsaw, in large part, because in order to win over the members, she had to sell them on an agenda that was in lockstep with their wildest dreams, likely knowing — and the Tory membership can't plead ignorance, because the former chancellor of the exchequer repeatedly warned them — that the bond markets would ruthlessly shred it.

Having the membership elect parliamentary leaders is a relatively recent innovation. The first U.K. Tory leadership race to use this model was 2005, the first Conservative Party of Canada leadership race to use this model was 2004. Most provincial parties in this country only started using it in the 1990s. We adopted our own crude primaries about a generation after the Americans themselves abandoned conventions as a means for selecting their leaders. It's unlikely that the shift, especially in Canada where we consume so much American political news, is much of a coincidence.

But the conflict remains. If the membership can hire them, and caucus can fire them, how long before a caucus rejects the membership's decision out of hand and sends a new leader packing right away? How much longer can fear of the base keep the guys actually tasked with the thankless job of governing in line? Just how dysfunctional can all this get?

I guess we'll have to find out the hard way.

Mitch Heimpel has served conservative cabinet ministers and party leaders at the provincial and federal levels, and is currently the director of campaigns and government relations at Enterprise Canada.

The Line is Canada’s last, best hope for irreverent commentary. We reject bullshit. We love lively writing. Please consider supporting us by subscribing. Follow us on Twitter @the_lineca. Fight with us on Facebook. Pitch us something: lineeditor@protonmail.com