Special Dispatch from Ontario: Guess voters were fine with the 'murder clown'

Ford isn't a titan. Twitter isn't real life. COVID isn't a factor anymore. And Del Duca would reject charisma like a donated organ.

Happy afternoon, Line readers. This is a special non-paywalled version of our dispatch, focused entirely on the Ontario election. We will send the normal end-of-week dispatch (covering everything else) to our paid readers, and the lite version to our free readers, on Saturday morning.

But now? So. Ontario, eh? Where to begin ….

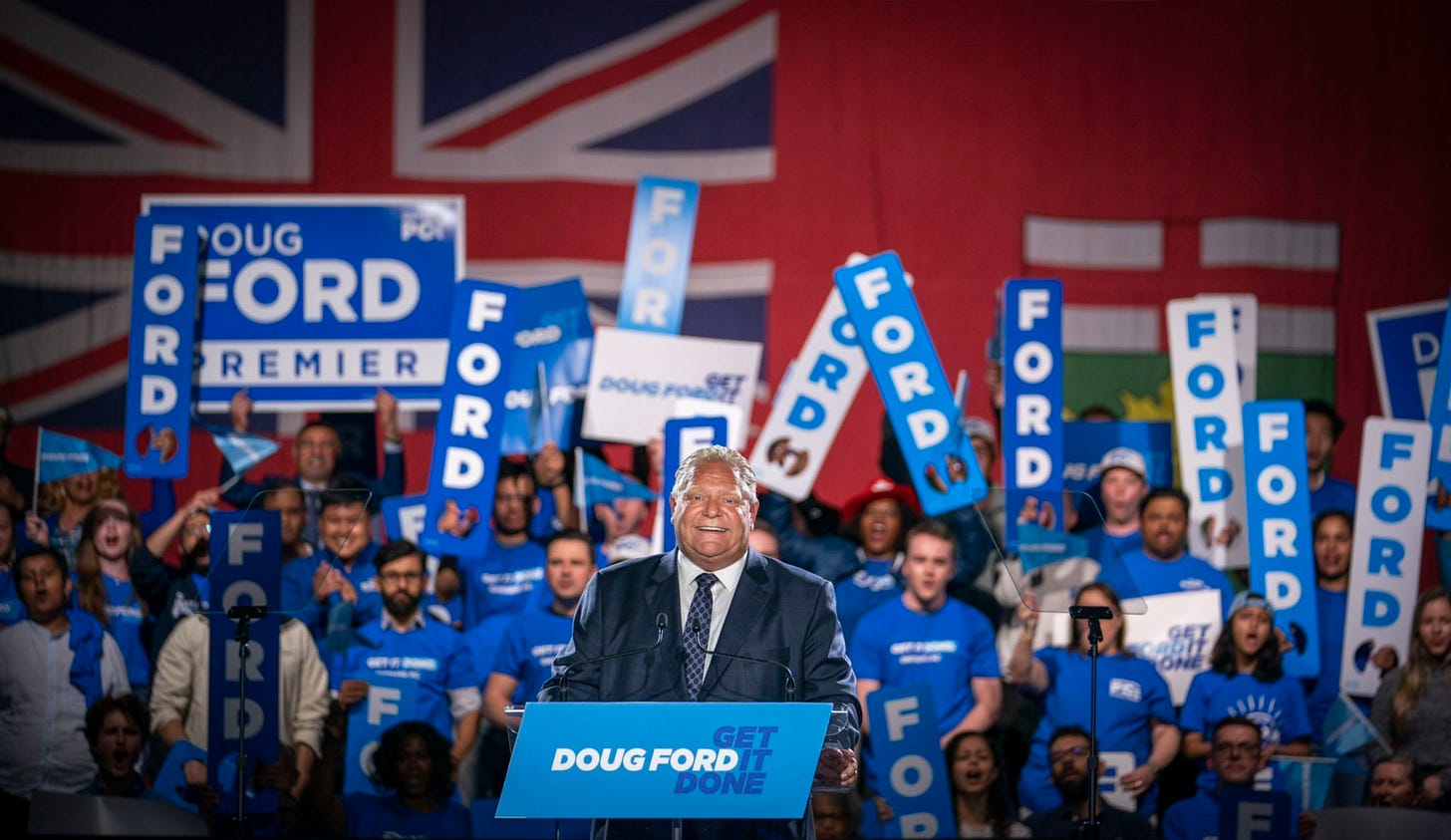

Here’s a place: Doug Ford and the Ontario Progressive Conservatives obviously feel pretty good this Friday. They really did about as well as they could possibly have hoped to do. Still, we urge our readers and all the analysts and pundits out there not to overreact to Ford’s victory. He’s not a political genius, he’s not some sort of colossus standing astride our politics, and he is not the man who must be immediately beamed into the federal Conservative leadership so that he can slay Trudeau's government and win 200 seats.

Doug? He's just a guy who got lucky last night. (Politically, we mean. Get your minds out of the gutter.)

We’re not taking anything away from Ford, or his campaign leadership, or all the people who worked hard for the PCs over the last month. They did a lot of smart things, they did them well, and they are reaping the benefits. It was an effective campaign. It rubbed a lot of people the wrong way, but your Line editors suspect it rubbed people the wrong way precisely because it was an effective campaign. Keeping Ford out of sight, avoiding a lot of questions, keeping things low-key … these weren’t accidents. These were deliberate decisions. You have to start any analysis of the PC campaign by granting that. Yeah, it was well conceived and well executed. A hat tip to the people behind it.

But the point that we want to make, and it shouldn’t take away from anything said above, is that the Progressive Conservatives maxed out the luck-o-meter. If this election had been a year ago, coming off the government's catastrophic handling of Ontario's third wave, it probably would have been Doug Ford resigning last night. The government caught an enormous break because factors well beyond its control shifted the public's focus off its greatest vulnerability, the management of the pandemic, and put it solidly on economic and cost-of-living issues that the PCs are much, much more comfortable talking about.

So yeah, the PCs had a good campaign, but you couldn’t buy that kind of luck. None of it happened in Ontario or even Canada. This was a global trend. After two years of pandemic, people are tired and they’re getting worried about other things. The timing for Ford could not have been better. So we absolutely give full credit to his campaign for a good job, but we also insist on acknowledging the huge role of luck and timing. We don’t know if it’s better to be lucky than good. But we certainly know it’s nice to be both at once.

We raise this as a note of caution before the punditry gets too carried away. This election is undoubtedly a huge victory for the Tories. But it is also a really, really weird election. The circumstances of it are very unique. The combination of low turnout, pandemic fatigue, Ford's personal political brand in Ontario, bizarrely lacklustre campaigns by the opposition, and a confluence of global trends that all netted out in Ford’s favour don’t tell us anything about the state of the conservative coalition in Canada, who would make a good federal leader, or what’s going to happen at the next federal election. This was a weird campaign during a weird moment in history. Adjust your hot-takes accordingly, friends.

All the above being said, we're going to briefly lean the other way. One election does not make a trend. But conservatives in Canada, federally and provincially, have been trying to lure blue-collar, working-class voters, particularly skilled tradespeople, away from the NDP and fold them into the conservative coalition. The conservative strategic case has been this: the modern progressive parties in Canada, especially the NDP, are being consumed by a focus on what we can somewhat lazily lump together under the description of "woke identity politics and virtue signalling." (Yes, we know that’s kind of a lazy summary, but it really does capture the conservative argument.) The conservatives concluded years ago that the progressive parties, and particularly the NDP, had become so focused on winning well-educated downtown white-collar professionals that they were opening up a huge opportunity to make inroads with blue-collar workers in smaller cities, suburbs and rural areas.

We won’t debate the merits of the conservative case today, or judge their analysis. Suffice it to say we think it is generally true, if perhaps somewhat overstated. (Voters are complicated, political theories usually aren't.) The important thing for our analysis here today is that it seems to have worked. Ford won in a series of ridings in the Windsor area, in and around Hamilton and in northern Ontario (Thunder Bay and Timmins, lookin' at you) that have traditionally been NDP strongholds on the basis of rock solid support from the working class. This was foreshadowed by a series of endorsements from labour unions and trade guilds representing private sector blue-collar workers in the run up to the vote.

Like we said, we’re not throwing out everything we know about politics as usual and starting from zero. But watch this, folks. The conservatives have been trying to do this since Stephen Harper's 2005 campaign. If they have finally begun to break through, this could indeed be a major realignment in Canadian politics, federally and provincially.

We aren’t prepared to declare this a fait accompli after one election. But you can believe that we will be watching this going forward. We suspect the NDP will be, too. If this isn’t a blip — if it’s the start of something — it’s going to be big.

Time will tell. Stay tuned.

We don’t think our remarks would be complete today without spending a brief moment looking at the opposition parties.

Oh boy.

Okay, let's do the NDP first. The NDP is probably feeling pretty good today. We get it. Even a week or two ago polls were suggesting they were about to lose their hold on official opposition to the Liberals. That would’ve been a disaster for the party. There’s no way around that. They’ve avoided that fate. The NDP has remained in second, although they lost a bunch of seats to the PCs (see above). In the days to come, the party is going to have to take a few cold showers, give their heads a vigorous shake, and realize that warm feeling they’re enjoying right now isn’t the afterglow of victory, it’s the fading adrenaline rush of a near-death experience. Avoiding annihilation shouldn’t be good enough. But that’s all they did.

Andrea Horwath, long-time leader of the party, has already announced that she is stepping down. And rightly so. The Line has some fondness for Andrea. God knows we’ve had the opportunity to get to know her during her tenure as provincial NDP leader, which basically overlaps entirely with our entire careers in journalism. She is a decent person with a better sense of humour than often comes across in public, and she has nothing to be ashamed about. She has taken the party as far as she can, and it’s time for someone else to take over and deal with what might be a changing environment — one that is not obviously changing in the NDP ‘s favour (again, see above).

If we have any words of wisdom for the NDP, it is probably simply this: you’re likely doing about as well as you could. We don’t think the NDP ran a great campaign. We don’t think they were nearly as aggressive in attacking Ford as they should have been. But that being said, we also don’t think they ran a bad campaign. It was basically fine, we guess? It seems to us that this election's particular circumstances notwithstanding, the fundamental problem the NDP has is that Ontario is not a particularly left-wing place. Our readers out west may scoff at that, but with respect, we don’t think many Canadians understand the nature of the Ontario public. It’s not made up of radically left-wing, mouth-foaming progressives. It’s a real mix of moderately socially progressive impulses wedded to a degree of fiscal conservatism, and above all, just huge dollops of Laurentian reserve. It isn’t a particularly left-wing place seeking to elect particularly left-wing leaders.

Maybe, strategically, a good opposition party is all that the NDP can ever hope to be in Ontario. If so, that’s a bitter pill to swallow for them. But if it’s any consolation, that’s generally what they were for the last four years. They could’ve done a lot better, they could’ve done a lot worse. And as part of their thinking going forward, we would encourage them to very honestly consider what their role is in Ontario's politics, and how best to fill it. Because we’re not convinced forming a government is all that likely anytime soon, barring a fundamental realignment in the province's politics.

Which, hey. That might happen. Because this brings us to the Liberals.

OMFG.

Writing critically about the Liberal campaign today feels a little bit like flogging a dead horse, and then shooting it a bunch of times, and then setting it on fire, and then hunting down all of its little horsey relatives and shooting all of them too. And then peeing on them. But still. It was a really bad campaign by the Liberals. The leader was bad. We’re sorry, but he was. If Steven Del Duca ever encountered charisma we suspect his body would reject it like a donated kidney. The party's campaign platform was a weird mishmash of stuff that sounded vaguely on point for 2022, but also often read like something copied and pasted directly out of Ontario Liberal campaign platforms going back as far as the 1990s.

Some of the problems the campaign experienced had easy explanations. The party's 2018 performance was so terrible they lost official party status, and the access to budgets and staff in the legislature that goes along with that status. The party has been trying to rebuild with at least one hand tied behind its back ever since. The campaign team was quite lean, and as a series of ejected candidates show, it was not able to properly vet the full slate of candidates it ran. You can understand how the lack of personnel and money contributed to those problems. But what we can’t understand is why the campaign insisted on making so many weird decisions. Handguns and abortion as campaign issues? In a provincial campaign? Talking up free transit rides, which will only appeal in the deepest downtown cores, where all they could do was hurt the NDP? A mid-campaign pledge to make COVID-19 vaccinations mandatory for school children, which was then never really mentioned again?

So yeah. Some of the campaign's problems you can write off as a result of money woes. Some of them were just plain bad decisions.

The Liberals didn’t just lose an election last night. They didn’t just lose an election and a leader, come to think of it: Del Duca resigned in the opening moments of his speech last night, having failed to get his party back to official status and having further failed to even win his own seat. On top of those things, they also lost a narrative. As Line editor Matt Gurney noted for TVO.org this morning, for the last four years, Ontario Liberals could have possibly convinced themselves that their annihilation in 2018 was a fluke. They had been in power a long time, they accumulated a lot of baggage, they made a few campaign missteps, and they got blown out. That can happen in politics. That easy explanation would’ve allowed the party to avoid a lot of painful, deep reflection, and they seem to have seized that opportunity to avoid the tough questions with gleeful abandon.

But they just got annihilated again. One blowout election you can write off as a fluke. But two? That’s a lot harder. The absolute best-case scenario for the Liberals is that they’ve been struck by lightning in consecutive elections. Maybe, just maybe, 2018 was a long-exhausted, scandal-prone government finally getting its due, and 2022 is just a weird, one-off bizarro campaign as the province exits a literal plague into a new era of economic upheaval and literal war. Desperate Liberals may well try to adopt this as their new narrative: it's not our fault, we're just snake-bitten.

We think that would be a mistake. We at The Line have written numerous times since the last federal vote that the general public does not understand how close to electoral oblivion Justin Trudeau came in this province nine months ago. The federal Liberals' much-vaunted "vote efficiency" is a pleasing euphemism for “won an awful lot of ridings by the tiniest possible margins." Trudeau won all those coin tosses last year, Del Duca seems to have lost them all last night. This raises serious questions about the size and resiliency of the Liberal voter coalition. Trudeau, for all his many faults, is a damn good retail politician, with tons of experience. And he barely squeaked out a victory here last year. Ontario's Liberals must ask themselves if they will be doomed to repeat the performance of the last two provincial elections until they find some provincial version of Trudeau, at least in terms of his political talent.

There’s no indication right now that there is anyone like that waiting in the wings for the Liberals here. And it’s an open question how many brushes with death this party can sustain before it ceases to be an effective political machine. Can they afford a third blowout?

Like we said before, we’re not reading too much into this election. It’s a weird one, and we are urging everyone to exercise restraint in their takes, including us. But if you are in Ontario Liberal, and you are not at least considering the possibility that you are now two elections into a non-recoverable death spiral, you aren't worth whatever little the party is able to pay you these days.

So. The above is about the campaigns. Let’s talk about how the rest of Ontario is coping, starting with this: Twitter is not real life. Will you all finally accept that?

Yes, we know that this is a trite phrase to use at this point, but if we at The Line have one major observation to note it's this. Twitter is not real life.

The Ontario election was historic — historic in that it might go down the least-interesting, least-passionate, least-buzzy election in modern Canadian history. Doug Ford won a healthy majority and an unequivocal second term amid an astonishingly low turnout (final votes are still coming in, but turnout seems to be tracking to something around the 43-per-cent range). And what this should tell you is that the majority of the electorate thinks he's fine. Not good. Not awesome, just adequate to purpose.

This giant shrug by the general electorate could not be more at odds with with the version of Doug Ford talked about on Twitter; and the more desperate and extreme the social media rhetoric became, the more confident we were that the consistent polling numbers were correct and that the Ontario PCs were sliding towards a complacent second mandate.

This is not to defend Doug Ford's record. Your Line editors have spilled many letters in recent years lamenting Ford's COVID policies, his budgets, his capricious flip flopping, and his all-around chaotic leadership style.

But there is simply no way to reconcile hysterical Twitter commentary about Doug Ford — ie; that he is an illegitimate, evil, Trumpian, demagogic murder clown — with the facts on the ground. If Doug Ford were so reviled by the general electorate, more of them would have showed up to the polls to kick him out of office. The weakness of the alternatives would not have mattered. He could have been deposed by a toadstool.

But he wasn't. Because Twitter isn't real life; and what passes for political discourse on that website is not an accurate or able reflection of what ordinary people think, say, and do.

Many of these points have already been made before, and so we don't want to re-hash old arguments, but in case anyone needs a reminder, Twitter is a minority pastime. It's frequented by laptop-class workers who live in fields such as communications and politics. The site is younger and more left-leaning than the general public. Its algorithms reward engagement and anger, which is best achieved by short-form outrage and snark delivered to an ideologically homogeneous audience.

In other words, if you are on Twitter, you are not normal. You are the exception, and you are speaking to, and hearing from, a narrow subsection of the population that broadly shares your lifestyle and worldview. You’ve self-sorted yourself into a social club with other people who’ve self-sorted into that same club, and you spend all day yelling at each other, or agreeing with each other, while ignoring 90 per cent of the population. And they get votes, too.

This is the real trap of the website. Twitter gives people the illusion of social or political engagement, but not the reality of the thing. It gives people the high of activism without the work or the results. Social media has created a simulacrum of the real world, one that sucks real energy, time and emotional investment, and redirects those finite resources toward its own parasitic advancement.

Some people use Twitter very differently. For them, it’s a place to follow sports or pop culture. That’s fine. But if you’re engaged enough in politics to read what we write here, you probably fall into the same camp as us. As we see it, Twitter is useful for exactly two things: self-promotion and therapy. Other than that, it's simply screaming into the void. The anti-Doug Ford tweet that generated 11,000 likes didn't move a single voter to or from the polls. It served only as an ephemeral ego boost to its creator, who channelled the euphoria of temporary peer approval right back down the Twitter slot machine in search of another hit.

Politics aside, we see this among writers all the time. Twitter is rife with personalities boasting enormous follower counts who struggle to make a poverty-line living. The time and energy spent generating likes and followers on Twitter come at the direct expense of productive, paid work. So when you see people with large Twitter followings sending their thoughts into the void, step back and consider what is really happening here: people working for free to generate content for a major tech company because this gives them the dangerous illusion of influence and control. It would be funny if it weren't so sad. So many talented and bright young people are just wasting themselves this way because it's easier than building a real or meaningful career, or spending time with friends and family, or devoting that energy to organizing for the causes they really care about.

If Doug Ford's re-election serves as a wake up call for anybody, then it will be a small blessing. Twitter is not real life. Spend your time and energy on things that are.

Further to this note, another takeaway from Doug Ford's win is that COVID is over. Or, rather, it's as over as it's ever going to be, in the realm of politics. With the benefit of hindsight, we'd put the end of the pandemic on February 24, the day Russia invaded Ukraine and we suddenly had another, less-tedious catastrophe to obsess over.

Over the course of this election, the pandemic barely came up at all. Ford's record of management simply was not a factor for most voters. How is that possible?

We at The Line have written a little bit about this phenomenon before. After a collective trauma that leaves society dispirited and shaken, the most common reaction seems to be a form of mass amnesia. We saw this after the 1918 flu, which was memory-holed for a generation. There are other historical examples as well: the victors of a war have something to champion, a new sense of shared identity and purpose. But the survivors of an ugly famine generally don't erect statues to their heroic emaciated dead. After something like this happens, people just want to put the bad years behind them and move on. When the fear abates, they want to return to normal as quickly as possible.

The end result is that ordinary people don't want to spend time reading COVID memoirs, or documenting the ins and outs of statistical death counts. Nobody really wants to endlessly re-litigate how we managed this pandemic — especially when the crisis is generally thought to be a once-in-a-lifetime event that will bear little relevance to future governance. The end result is that leaders like Doug Ford get a giant mulligan on the COVID file, and he won't be the only one. Do you think anyone is going to want to debate the finer points of federal pandemic policy in two years? We highly doubt it.

There's a dark side to this habit, of course. Because we don't wallow in our failures, we tend to avoid learning from them. We suspect that it will be another generation before scientists and analysts can tease out the best and worst lessons from the COVID pandemic, and another generation after that before we can apply them to future pandemics. The one thing we are clear on? Barring any wildcard future variants, as a political factor in North America, COVID is over.

We at The Line are also pretty sick of all this bitching about how the media covered the Ontario election. The MeDiA warned you that polling hadn't shifted over the course of the election campaign. The mEDiA covered a dull, lacklustre campaign in which the opposition parties failed to capitalize on Doug Ford's manifold weaknesses. The meDiA warned you that the likely result would be a Doug Ford majority government. Basically, the MEDiA told you the thing that was probably going to happen, and it happened.

The anger at the MEdiA seems to be rooted in some kind of belief that it is collectively responsible for how people think, act, and, thus, vote. That's not how this works. That's not how any of this works.

We would be remiss to fail to point out that there is often a symbiotic relationship between media outlets, pollsters and the collective consciousness of the general public. But this is not a uni-directional relationship. News outlets put up a collection of stories; the public engages with content that it finds useful or interesting; news outlets take note of this and, over time, direct resources accordingly. To what extent does covering polls predict the outcome of an election by creating a self-fulfilling prophecy vs. merely reflecting the popular will? This is a chicken-and-egg problem. We at The Line remain skeptical of polling precisely because we can't confidently answer that question; we have long thought that media outlets have grown far too dependent on sometimes weak polling because it's easier and cheaper than other forms of political coverage.

Let us briefly explain what we mean. Let’s say Societal Issue X is in the news for whatever reason. A paper or TV station can assign a reporter to cover Societal Issue X, even though they may have zero expertise in it, and no time to do more than basic research. Or the paper or TV station can interview a pollster who can tell you how the public already feels about Societal Issue X, because they’ve touched on that issue before. The pollster, meanwhile, is happy to do the interview — it boosts their profile, and helps them make more money by getting more paying clients, like big corporations doing market research to help them sell more sugary drinks or deodorant. It’s a win-win for the publicity seeking pollster and the resource-starved news outlet.

But we will also note that the era of ubiquitous horserace coverage has not coincided with a lack of political upheaval. We've seen plenty of examples in recent years of incumbent parties calling elections — and then dramatically crashing and burning come election day. Sometimes these shifts in popular sentiment have been reflected in the polls. Other times, not so much.

So forgive us if we maintain some skepticism that Steven Del Duca would be premier of Ontario right now if only the MEdIA had covered the race slightly differently. In a way, it’s proof that we’re damned if we do and damned if we don’t in this business. Ontario’s media coverage of what was happening in the campaign, and the likely result, was bang on. And people are mad at us for not changing the outcome to something more to their liking. Are they sure that’s what they want us to make a habit of doing?

Okay, folks, that’s our special edition dispatch for the Ontario election. The normal dispatch (with video and podcast) will go out tomorrow morning. If you want to make sure you catch the full version of that, please help us out by subscribing below.

The Line is Canada’s last, best hope for irreverent commentary. We reject bullshit. We love lively writing. Please consider supporting us by subscribing. Follow us on Twitter @the_lineca. Fight with us on Facebook. Pitch us something: lineeditor@protonmail.com

I am reminded of a story I once read about Emperor Napoleon, who was considering whether to promote one of his generals to the rank of Marshal and he asked his advisors whether the general had the qualities to be a Marshal. "He is brave as a lion," said one advisor. "He's very smart", said another, "and rarely makes mistakes." A third pointed to his charisma and said that his troops adored him.

"Yes, yes," said the Emperor impatiently. "That's all very well, but is he LUCKY?"

Doug Ford may be a lot of things, but he isn't an ideologue. One of The Line editors, I think, nailed it when they said that he isn't a politician, he's a salesman -- one that wants to do whatever deal is in front of him.

That is reflected in the flip-flops in policy as he seems to follow public opinion. Sometimes it felt like Ontario crowdsourced our COVID response in slow motion. The government would do a thing. Polling would show the public hated it; experts would explain why it was a terrible idea. A week or two later, the government would flip flop, repeating the process until things got better and/or public opinion settled down. Ideologues don't do that.

It's a pretty inefficient way to govern. Moreover, this Ontarian is left with a strong sense that certain groups (donors, big companies with good GR teams) tend to get a lot more "deals" than anybody else. It's probably why Costco and Walmart seemed to be impacted the least by pandemic restrictions while Mom-and-Pop shops had to figure out curbside service. It's probably why we're getting a new highway that nobody except a small group of developers (and probably construction companies) want. I'd call it corrupt, except I honestly think it's just Doug trying to get a deal -- running Ontario like its a super-sized label company.

What's significant about this election is that the PCs took ridings from the NDP, which doesn't happen very often in Ontario and points to a real shift as places where skilled trades or manufacturing are important start to look at the PCs. They earned that shift, it's no fluke. The labour minister has worked hard over a number of years on programs to promote skilled trades and built real relationships. A lot might be odd about this election, but those wins were the result of some hard work and good strategy. We'll see if they can hold those ridings.