Stephen Gordon: Criticizing the Bank of Canada is fine. But get the criticisms right

No, it did not cause the recent surge in inflation by “printing money” because it didn’t even print money.

By: Stephen Gordon

I am not one to mount a full-throated, unconditional defence of the Bank of Canada. I think that as we moved to the latter part of 2021, the Bank focused too much on the supply-supply explanation for inflation, and did not focus enough on what was going on the demand side. The Bank should have started tightening months before it did, and even now, the stately pace with which it has chosen to act puzzles me. So yes, there are good reasons to criticize the Bank’s conduct of monetary policy.

That said, there are some bad criticisms, and they have become the cornerstone of Pierre Poilievre’s campaign for the CPC leadership. They are also getting a lot of traction; a couple of them made an appearance here on The Line last weekend.

The tl;dr version: No, the Bank of Canada did not cause the recent surge in inflation by “printing money” because it didn’t even print money.

Let’s start with former Governor Poloz’ warnings of deflation back in May 2020, and let’s try to do it without the benefit of hindsight. I know it seems odd to think of now, but central banks in the advanced economies spent much of the decade preceding the pandemic struggling – and largely failing – to create inflation in the aftermath of the 2008-09 financial crisis: deflation was the danger. Here in Canada, inflation ran consistently below the Bank’s two per cent target for most of the decade. Again, I know that this sounds to a non-economist like an odd problem to be trying to solve: what’s wrong with deflation? Wouldn’t it be great if the prices of things we wanted to buy kept falling?

No, it wouldn’t be great. In fact, it would be very bad. When deflations have occurred in the past, it has always been in the context of a depressed economy: think of the Great Depression.

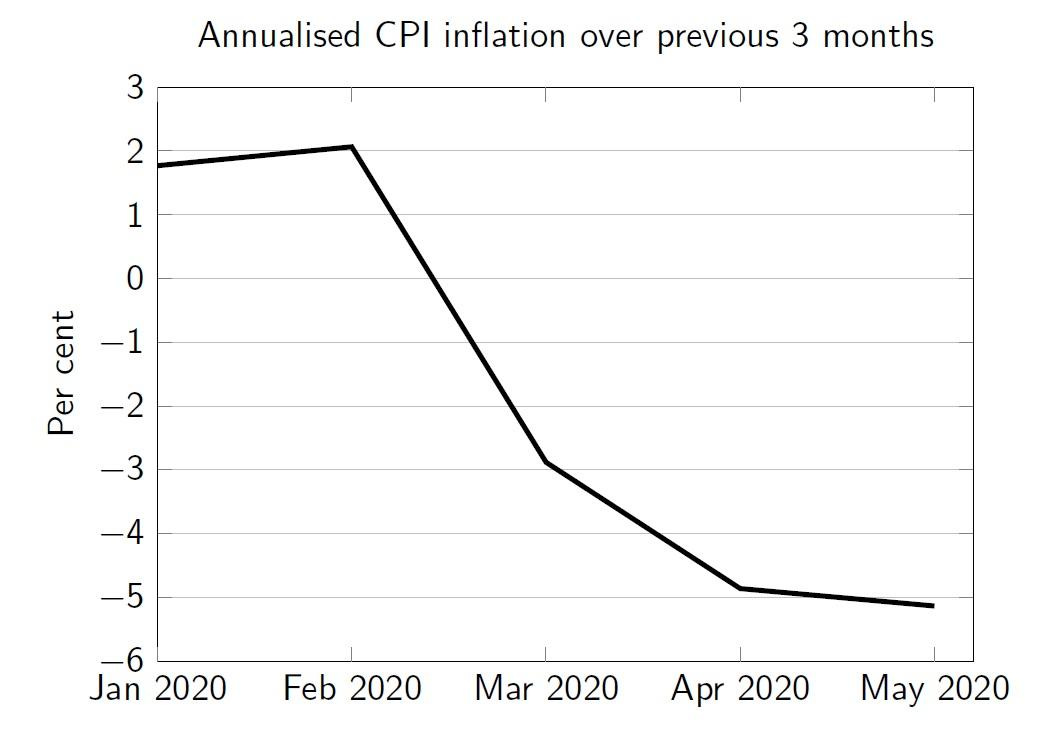

So let’s look at the inflation data Steve Poloz was looking at back in late May 2020 (the May CPI hadn’t come in yet, but he would have seen some preliminary numbers):

So worrying about deflation is exactly what the Bank of Canada should have been doing in May 2020. The fact that it didn’t happen doesn’t mean the Bank made a mistake. It would have been a worse failure if the Bank had warned of deflation and it happened anyway.

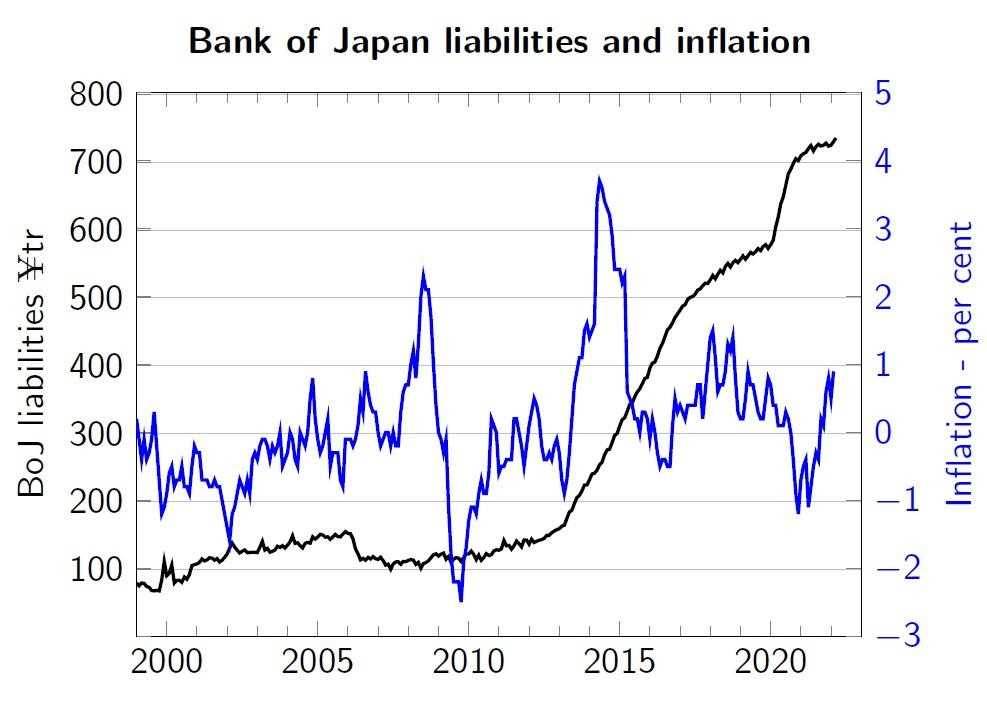

I know, I know. At this point Poilievre would doubtlessly reply that the Bank of Canada’s balance sheet had expanded by a factor of five. Runaway inflation was the obviously predictable result, right? Well, tell it to Japan.

Japan had been struggling with low inflation since its own banking crisis in the 1990s. Finally in 2013, the Bank of Japan decided to increase the size of its asset holdings, coincidentally also by a factor of five:

The predicted effect on inflation didn’t occur:

The best explanation I can find for why not is in David Andolfatto’s blog post “The failure to inflate Japan.” The basic problem is that when interest rates are very low (as they were then in Japan and were here in early 2020), there’s not much difference between “money” and government bonds: both are equally safe assets yielding essentially the same return. The “money” that the Bank of Japan created to buy all those bonds didn’t actually go into circulation; it just sat there in private balance sheets. (I’m pretty sure I over-simplified David’s point.)

I don’t know the Bank of Canada’s thinking at the time, but I certainly wouldn’t be surprised if they figured that with interest rates at zero, the proceeds of those bond purchases wouldn’t actually circulate in the economy.

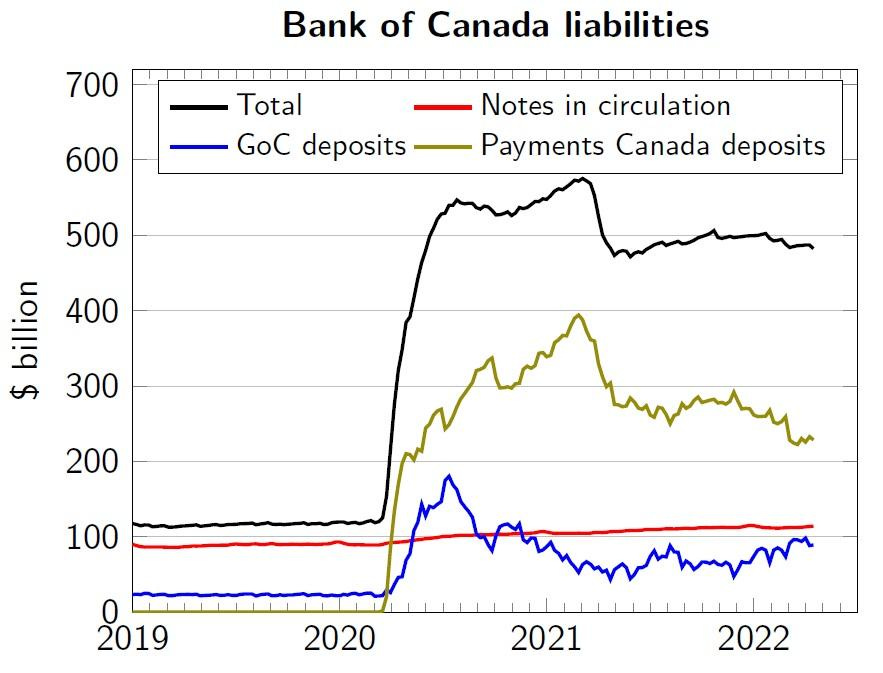

And this is pretty much what happened.

The volume of what most people think of as money – currency notes in circulation – has stayed flat during the pandemic.

A crude summary of what happened goes like this:

The federal government issued a large amount of bonds, and chartered banks and other members of Payments Canada purchased them

The Bank of Canada purchased those bonds on the secondary market.

The chartered banks deposited the proceeds of those sales at the Bank of Canada, where they still sit. The Bank of Canada pays interest on reserves, so as long as interest rates were so low, the chartered banks were in no hurry to withdraw them and loan them out.

Contrary to the overused meme, the money printer did not go brrrrr. Economists have long stopped making a direct link between anything in the central bank’s balance sheet and money, mainly because so few transactions involve cash or anything that the Bank of Canada can control.

If you’re wondering why the Bank of Canada bought those bonds in the first place, the answer is that it also has a responsibility to keep financial markets running smoothly. The federal and other governments needed to borrow massively in a very short time, and private borrowers – think of people who happened to need to renew their mortgages in April 2020 – would have found themselves squeezed out of the market. A spike in interest rates was the last thing we needed at the time.

So who or what is to blame for the surge in inflation? Andolfatto again, on “The inflation blame game”:

If there was a policy mistake, it was in not having a well-defined state-contingent policy beforehand equipped to deal with a global pandemic...

Policymaking in real-time is hard. And policy, whether formulated beforehand or not, must necessarily balance risks. There was a risk of undershooting the support directed to households... And there was a risk of overdoing it in some manner.

As things turned out, the federal government did overdo it. Although the goal of the income support measures was to replace lost disposable income, they ended up doing more than that: disposable income – especially for low-income households – actually increased during the pandemic.

I’m not inclined to view this as a mistake deserving of much blame: this was a once-in-a-century crisis that required a massive response without the luxury of taking time to think. Employment had fallen 15.6 per cent between February and April, 2020; in comparison, job losses during the Great Depression were less than two-thirds as big, and were spread over the space of four years. No one knew in April 2020 that vaccines would be widely available in less than a year or that the job losses would be recovered some 18 months later. But as the Bank has finally come to realize, the inadvertent boost in demand generated by what were in hindsight overly-generous income support programs is now manifesting itself as inflation.

The Bank of Canada can be fairly criticized for being slow to react to the surge in inflation, and indeed Governor Macklem has admitted as much. But as David Andolfatto notes, if anyone really is to blame for causing the inflation, it is all governments — past and present, of all stripes and levels — for not having thought harder about what might have to be done during a global pandemic.

Stephen Gordon is a professor of economics at Universtié Laval.

This piece has been updated to correct the spelling of economist David Andolfatto’s name. We regret the error. (To be clear, it was the surname. We didn’t screw up “David.”)

The Line is Canada’s last, best hope for irreverent commentary. We reject bullshit. We love lively writing. Please consider supporting us by subscribing. Follow us on Twitter, we guess, @the_lineca. Fight with us on Facebook. Pitch us something: lineeditor@protonmail.com

Gawd, I can't remember back far enough to the last time someone tried to excuse money creation by claiming that no money was "printed". Accompanying it with a graph of "notes in circulation" is over the top.

"Money printing" actually refers to the creation of money -- not actually printing bills on a printing press.

"Issuing credit" becomes "money printing" when the credit is spent. And the governments' borrowed and spent during the pandemic. This is the cause of inflation. So, yes, money was printed.

Currency notes make up a very small percentage of what we call money in the economy. The Bank of Canada created money not by printing bills but by purchasing debt from the government at an unprecedented rate. This money doesn't come from anywhere, the Bank of Canada does not have some giant account of Canadian dollars to just doll out to the government whenever they need to stay afloat. So, the Bank of Canada creates money in a computer account and uses that newly made money to purchase the bonds and the government takes the newly created money from those bonds and spends it, but nowhere in this process is there ever actual money created. Which makes your whole post disingenuous because no central bank "prints money" but actually printing money. We do it with either central bank bond purchases or, in Canada, through the Charter banks creation of money when loans are made like for a mortgage.