Tim Thurley: How the great Canadian gun compromise was destroyed

Gun-control groups used to be realistic about the scope of their goals and the Canadian way of life. That's changed.

By: Tim Thurley

We Canadians love compromise. As many individuals and groups — myself included — descended on Ottawa to discuss C-21, the federal government’s now-passed firearms law, senators asked witnesses how to reconcile the views of anti-gun groups and gun owners into a coherent whole. They can’t. It has become clear that gun-control advocates will no longer allow a workable, lasting compromise. It isn’t Grandpa Joe’s movement anymore, if it ever truly was.

The simple truth is that Canada already had a hard-fought gun compromise, the conclusion of a process carried out through the Trudeau the Elder, Mulroney, and Chretien governments. Firearms of most types remained available to the law-abiding license holder, subject to increased government oversight, approval, and conditions to prevent misuse. Strict licensing, safety courses, background checks, mental health and substance abuse disclosures, storage requirements, spousal sign-off, and additional safeguards were enshrined in law.

The three major bills (Bill C-51 in 1977, Bill C-17 in 1990, and Bill C-68 in 1995) made some hunting and sport shooting activities harder, but also largely preserved their existence and their important place in our federation. The bills were massive exercises. C-68 engaged large swathes of society from labour unions to provincial legislators. Despite some inconsistencies and overreaches, these were defensible public-policy exercises.

Gun control groups had gotten most of what they’d wanted. That wasn’t surprising. They had actively participated in drafting legislation and worked directly with senior bureaucrats. Allan Rock’s policy advisor called their contributions “very instrumental.” In 1995 Heidi Rathjen of gun control group PolySeSouvient said, in response to Pierrette Venne’s question about what the group would do if Bill C-68 came into effect, that “...if [Bill C-68] is passed as it was tabled, without major amendment, then, as far as we are concerned, after what we've presented today, we will no longer fight for a federal legislation.” No major amendments were made. In 2015 she essentially re-endorsed their 1995 position, and blamed their continued activism on Harper-era tweaks and the post-1995 invention of “new” “assault weapons” — though many of the “assault weapons” her group wanted banned were on the market decades prior to C-68, were not prohibited by it, and remained legal until 2020.

C-68 was touted as the “end of the struggle to strengthen gun control in Canada.” While some advocates pledged to continue a push for a total ban on the remaining murkily-defined “military assault weapons,” the compromise was set. Subsequent Liberal and Conservative governments accepted the core philosophy and most core elements. The 2004 Conservative manifesto retained all of the central components except for the controversial, expensive, and ineffective registration of hunting guns, a position eventually supported by Trudeau the Younger.

Gun-control groups used to be realistic about the scope of their goals and the Canadian way of life. They acknowledged hunting and sporting use, the importance of having “a supply of ammunition in the home” for predator defence in rural areas, and maintained that the Chief Firearms Officers should have discretion over license issuances or revocations when a person has been rehabilitated, a policy which C-21 would abolish. They didn’t even push for a total ban on handguns. In turn many gun owners came to see licensing as a point of pride. They saw it as a badge of honour indicating they belonged to the safest and most trusted citizens, clearly set apart from the criminal class and even safer than the general public.

Had gun control advocates stopped there, they may have been accepted as credible moderates.

Instead, the compromise is now being torn apart by the advocates who fought so hard to establish it in the first place. The first sign is the hard-fought backing of C-21, advocating against even basic exemptions for highly regulated competitive sportsmen. It goes far beyond the C-68 compromise in multiple ways, from its erosion of due process to its slow, completely uncompensated ban on handgun ownership with almost no exemptions even for uses widely considered safe, legitimate and desirable.

The second sign is the full-court press for what’s next, since gun control groups considered even the overreaching C-21 that engendered such anger from Indigenous groups, hunters and sportsmen a “betrayal.” Two recent releases by separate groups provide a glimpse into what’s coming.

A petition published in Le Soleil and endorsed by PolySeSouvient and multiple Quebec student activists called for the usual “assault weapon” ban, but added a demand for prohibitions on “high-precision” rifles, semi-automatics, all larger calibres, all firearms that can hit targets at a great distance, and a great number of accessories that could be attached to these firearms, including bipods.

If you’re familiar with firearms, that covers most of the market, including many scoped hunting rifles. Following the precise wording it would cover the Lee Enfield, Canada’s quintessential hunting rifle sold in the millions and quite literally distributed to First Nations. Together with current regulations on businesses that would mean the effective end of a feasible Canadian firearm market. Sloppy wording? Perhaps. But this is also part of a pattern: the same organization called a bolt-action rifle manufacturer an “assault weapon dealer.”

Then came the horrific familicide in Sault Ste. Marie, Ont., conducted by a person who had a past firearm prohibition. The co-founder and main spokesperson for Doctors for Protection from Guns (DFPfG), responsible for the infamous “it’s the guns, it’s the guns, ban civilian ownership of guns” quote and the unconvincing clarification that she only meant some guns, gave an enlightening interview to the Sault Star. I encourage you to read it in full because I could avoid writing another word and my thesis would stand on that interview alone.

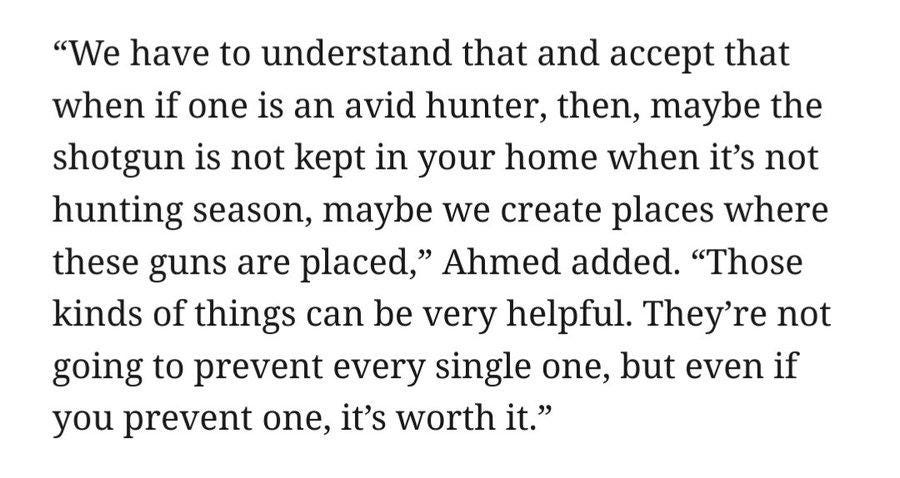

In direct contradiction to their oft-stated view that we just need British-style rules, which I’ve made clear will not work in Canada, the piece implies that only shotguns are understandable for a citizen to own. It demands a significant reduction of firearms in Canada and explicitly advocates central storage. It is not an out-of-context or one-off statement, but the latest in a clear pattern. Indeed, it was retweeted by a physician and then in turn retweeted by a key ally of DFPfG with the caption “zero guns should be kept in a Canadian residence.” That’s a gun control regime far closer to China’s than to even the United Kingdom’s strict rules, and to them it’s worth it if it saves just one life, or perhaps even if it doesn’t.

I wish we could save every life, but the harsh reality is that saving just one life is a rhetorical flourish and not the basis for practical policy. We all know why: if we spend a billion dollars to save one life often enough, pretty soon the federal treasury will be too empty to save anyone.

These groups consider removing firearms from society an unalloyed good, yet consumer demand shows plenty see it differently. There are 2,300,000 licensed gun owners in Canada who rely on firearms for needs as diverse as agriculture, sport, wilderness protection, trapping, investment, heritage and hunting. Fifty thousand jobs and billions in GDP rely on them. Loss of livelihood is bad enough, but we also cannot ignore the loss of life that economic harm entails or that every dollar we spend or lose here could be spent on a nurse we do not employ, a soldier without proper equipment, or a diversion program for an at-risk youth.

For fun, I once roughly estimated the building costs for central storage units using comparable public contracts. It came to just over $600 million, before any operational costs. Six hundred million bucks is a lot of money in any scenario, but here’s the kicker: that’s for only 20,000 guns, in just the Northwest Territories. Where guns are critical to food security. Canada has about 12.5 million firearms. There’s a reason almost no serious comparator uses central storage, even in far smaller countries.

On the other side of the equation, very little evidence supports the extreme costs of their proposed measures. Overall suicide rates generally don’t change when you ban guns, at least where licensing and other reasonable barriers to entry exist, as they do in Canada. Indigenous hunters say semi-automatic rifle bans will put their lives at risk, forget limiting them to shotguns. Rigorous statistical analysis shows banning semi-automatics, a policy that will cost billions to remove just a few models, doesn’t reduce homicide. Of the three largest mass murders in Canada since the Firearms Act came into force, not one was committed with a legally owned firearm. Government statistics released by ATIP show two of the eighty-four total intimate partner homicides in 2020 were committed by a licensed gun owner with a firearm of any type. We are already minimizing risk to the extent reasonably possible.

Worse still, the lower the numbers get, the harder it is to find reliable statistical evidence that the policy saved anyone at all. Policy can’t be unfalsifiable if it is to be evidence-based. We can debate the weight of relative priorities, but imposing costs without measurable improvements is detrimental to our society.

Therein lies the problem. Despite occasional lip service to tolerating some uses, like hunting, there are few gun-control measures these groups actually denounce, regardless of impact or impracticality. Their written calls to action show they’re on board with just about anything: banning big-bore guns, even though these heavy, expensive firearms are so rarely used in criminal activity that even Britain failed to find a reason to ban them; calling suppressor legalization “insane” even though they’re allowed in Britain and unregulated in Norway; and, of course, advocating central storage of shotguns, which is so ludicrous it’s almost a self-disqualification. Anything goes, as long as it’s on a one-way street.

Why make such a blisteringly radical jump from hard-won Canadian compromise to proposals that go well beyond one of the strictest countries in the democratic world? Is it a conscious attempt to shift the Overton window? Is it political pressure on a limping government? Or arguably the most concerning, is it a genuine mask-off moment of the sort that has become depressingly common?

Canada must take a sincere public-policy perspective that aims for the right amount of gun control. The simultaneous dangers and the inherent importance of firearms mean that the right amount is somewhere between “total ban” and “none.” It’s possible to disagree, and strongly, about where that line is. It’s not possible to have that discussion when the groups whose risk tolerance is near-zero, a standard applied to almost no other major consumer good, have driven the debate.

That’s key. Were these groups shouting their ideas into the ether, perhaps then this article would be a mere curiosity. Unfortunately, the government has been making policy decisions under their pressure. As it continues and experiences unexpected pushback, government is discovering that the zero-sum approach does not translate to workable policy. Indeed, their latest proposal to criminalize the possession of almost all magazines — and their attached rifles — in Canada despite that proposal being a literal order of magnitude larger than their still-unimplemented “assault-style firearm” buyback program shows they’re not even trying. Better is always possible, but so is worse, and that’s what we’re getting.

When he initially came to Ottawa, Minister Rock wanted nobody but the police and military to have guns, but breaking out of his bubble broadened his view. Meanwhile, this government has treated the rights of Indigenous people and the pleas of rural gun owners, sport shooters, Olympians, civil liberties organizations, the provinces, and more as a simple political problem to overcome. Groups pointing out significant problems with the government’s approach that could have been mitigated with amendments were gaslighted and told they did not represent gun owners.

Gun owners noticed. Canadian gun owners are not radicals. They are a group that actually wants compromise and regulatory predictability, but have reacted with disillusionment and despair to ever-changing rules that even seasoned observers like myself have difficulty tracking. The government’s own polling bears out that a fifth of gun owners will flatly refuse to participate in the “buyback” program regardless of incentive, more than double the figure from a year ago. Why should they? We have the statistical background to show they are not the problem, and yet despite successive negotiations the crusade against them accelerates with renewed vigour.

In 1995, Liberal MP Sue Barnes said that “...[a] good law has to be accepted by the people to be relevant legislation. I think that's primary in understanding the legal system.” Senator Boisvenu made the same point during the November 6, 2023 C-21 hearings. They’re right. Law requires enforcement, but in democratic states the practical ability to enforce is predicated on the knowledge that most people comply voluntarily, because they trust in the validity of the law itself or in the system which underpins it.

Yet somehow this critical point, raised twenty-eight years apart by members of different parties, isn’t being considered. And as smuggled and 3D-printed firearms require more enforcement resources to avoid increasing criminal proliferation, the government will be forced to waste those resources enforcing useless laws on peaceful sport shooters and hunters despite legal firearms being a small portion of the problem.

Every policy involves trade-offs. There's no way around that reality. By seeking primarily to appease an increasingly radical anti-gun lobby and leave poison pills for the opposition, the government has alienated the stakeholders whose cooperation is essential to navigate towards the law’s success.

The ideological commitments have shifted, and the Canadian gun debate has declined with them to an unserious place utterly disconnected with not just the realities faced by gun owners, but of policymaking itself. The next Canadian government must return to a reasonable, stable, and realistic course. They will not do so by listening to a gun-control movement that has lost all sense of balance or perspective.

Tim Thurley specializes in firearm policy, having earned a Master of Science from Leiden University with his analysis of the long-gun registry’s lack of effect on Canadian homicide rates. He lives in the Northwest Territories, where he files regular Access to Information requests on firearm issues and anything else of interest.

The Line is entirely reader funded — no federal subsidy for us! If you value our work and worry about what will happen when the conventional media finishes collapsing, please make a donation today.

The Line is Canada’s last, best hope for irreverent commentary. We reject bullshit. We love lively writing. Please consider supporting us by subscribing. Follow us on Twitter @the_lineca. Fight with us on Facebook. Pitch us something: lineeditor@protonmail.com

Great article on one of Canada's long-standing stupid arguments. Anti-gun groups seem to be searching for some utopia where if there are no guns, no one will ever be hurt. It's naive and delusional thinking. Canada's gun problem is its border, and now, 3D printing. It has never been the legal gun owners who should be proud of the hops they have to jump through. he beauty for politicians is it's the "shiny object" they can talk about as a distraction from all the other things they're failing at so it appears that they're doing "something". Same laws are just fine as they are. Canada's gun laws are the perfect example.

I used to be strongly on the other side of the gun issue, but this article and similar ones by Matt have totally won me over. I was wrong.

That's one of the things I love about substacks like The Line. They're proof that good faith arguments and debate really can change people's minds. That's often hard to believe these days but something I'm grateful for this Xmas.