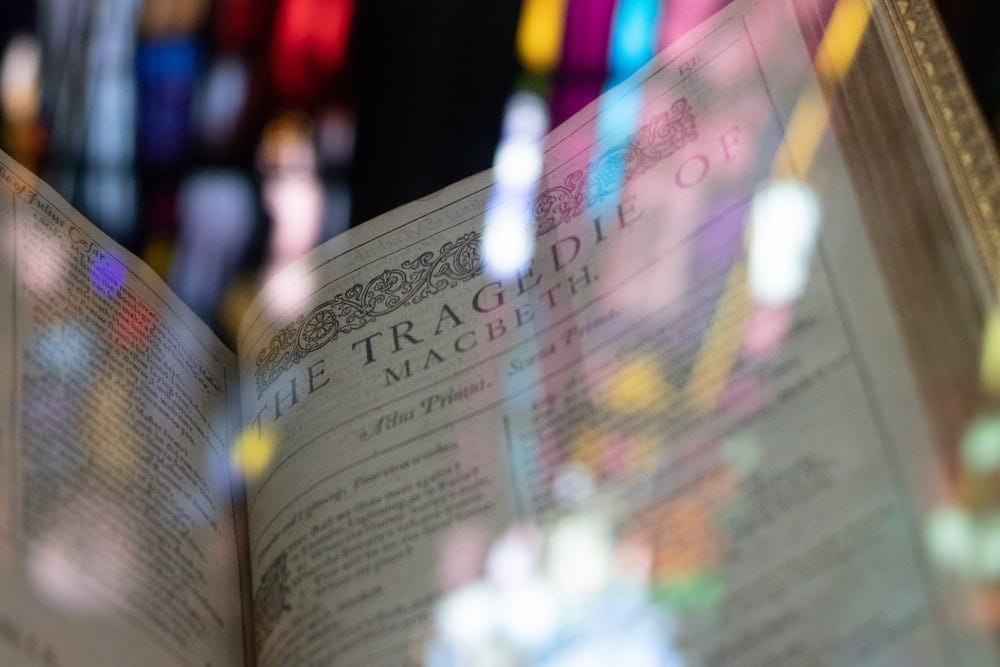

Flipping the Line: Cancelling Shakespeare would rob students of a chance to think for themselves

Shakespeare’s work is profoundly amoral, his plays and poems refuse to provide us with an objective moral code.

The Line welcomes angry rebuttals and responses to our work. The best will be featured in our ongoing series, Flipping the Line. Today, Sky Gilbert replies to Allan Stratton’s recent plea for high schools to cancel Shakespeare.

By: Sky Gilbert

In his article “Cancel Shakespeare,” Allan Stratton argued eloquently in favour of teaching Shakespeare’s work in schools — but teaching it “better.” He suggested that Shakespeare should be taught in small doses — that is his “pride of place” should be shared with other writers. He also reminded us that student exposure to hip, sexy, modern cinematic interpretations of Shakespeare (like Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo and Juliet) will help draw students to the bard’s work.

I agree with his last point; as a teacher myself it strikes me that anything that will lure students into reading a good old-fashioned book these days — well, that’s a good thing. But I respectfully disagree with the rest of Allan’s thesis.

Allan is a friend of mine, and friends may not always be of the same mind on every topic. If everyone doesn’t come to understand this, soon, that friends can respectfully disagree, we may never claw our way out of the polarized sinkhole that is now drowning us all. In that spirit, here’s what Allan missed.

Allan thinks that Shakespeare’s language is difficult and old fashioned, and that students today find analyzing the complexities of his old-fashioned rhetoric boring and irrelevant. Yes, Shakespeare essentially writes in another language (early modern English). And reading or even viewing his work can be a tough slog. Not only did he invent at least 1,700 words (some of which are now forgotten today), he favoured a befuddling periodic syntax in which the subject does not appear until the end of a sentence.

But a study of Shakespeare’s rhetoric is important in 2021. There is one — and only one — exceedingly relevant idea that can be lifted from Shakespeare’s congested imagery, his complex, sometimes confusing metaphors — one jewel that can be dragged out of his ubiquitous references to OVID and Greek myth (references which were obviously effortless for him, but for most of us, only confound). And this idea is very relevant today. Especially in the era of “alternate facts” and “fake news.”

This idea is the only one Shakespeare undoubtedly believed. I say this because he returns to it over and over. Trevor McNeely articulated this notion clearly and succinctly when he said that Shakespeare was constantly warning us the human mind “can build a perfectly satisfactory reality on thin air, and never think to question it.” Shakespeare is always speaking — in one way or another — about his suspicion that the bewitching power of rhetoric — indeed the very beauty of poetry itself — is both enchanting and dangerous.

Shakespeare lived at the nexus of a culture war. The Western world was gradually rejecting the ancient rhetorical notion that “truth is anything I can persuade you to believe in poetry” for “truth is whatever can be proved best by logic and science.” Shakespeare was fully capable of persuading us of anything (he often does). But his habit is to subsequently go back and undo what he has just said. He does this so that we might learn to fundamentally question the manipulations of philosophy and rhetoric — to question what were his very own manipulations. Shakespeare loved the beautiful hypnotizing language of poetry, but was also painfully aware that it could be dangerous as hell.

In fact, Shakespeare’s work is very dangerous for all of us. That’s why students should — and must — read it. Undergraduates today hotly debate whether The Merchant of Venice is anti-Semitic, or whether Prospero’s Caliban is a victim of colonial oppression. Education Week reported that “in 2016, students at Yale University petitioned the school to ‘decolonize’ its reading lists, including by removing its Shakespeare requirement.”

It’s true that Shakespeare is perhaps one of the oldest and whitest writers we know. (And sometimes he’s pretty sexist too —Taming of the Shrew, anyone?). But after digging systematically into Shakespeare’s work even the dullest student will discover that for every Kate bowing in obedience to her husband, there is a fierce Lucrece — not only standing up to a man, but permanently and eloquently dressing him down. (And too, the “colonialist” Prospero will prove to be just as flawed as the “indigenous” Caliban.) William Hazlitt said: Shakespeare’s mind “has no particular bias about anything” and Harold Bloom said: “his politics, like his religion, evades me, but I think he was too wary to have any.”

Philosophically, Shakespeare was a skeptic; likely he devoured the work of Sextus Empiricus. Sextus’ writings were eminently available in British universities in the 1500s, and he is explicitly referenced by Shakespeare’s pals Thomas Nash and Ben Jonson. Shakespeare subtitled Twelfth Night “What You Will” — and indeed he seems to think that it is not his job to provide us with the meaning of his work, but rather to force us to hear — and perhaps buy into — differing points of view. This was precisely the method of Sextus Empiricus. A skeptic thinks the path to bliss can only be found after ruthless examination of each side of any question. Sextus did not believe there was an answer, but that rather somehow we must rest in an epiphany of uncertainty. For Sextus, “the practice of placing arguments and counterarguments in contact with each other [was] in order to show the impotence of both.” If you examine Shakespeare’s work carefully you will see that it is steeped in paradox, and replete with unresolved arguments. Shakespeare was, it seems, almost constitutionally incapable of expressing something without expressing its opposite (“fair is foul and foul is fair”).

This is why Shakespeare’s work must remain part of the literary canon; because his work forces students to think outside the box — to explore outrageous and unsettling ideas. Shakespeare’s work is profoundly amoral, his plays and poems refuse to provide us with an objective moral code. They do not tell us how to act, how to think, or how to live. It’s no surprise that the woke folk find it threatening.

I hope my friend Allan will agree with me on some of this, as I have used most all the techniques of persuasion that I have at my disposal. I’ll top it all off by mentioning that Shakespeare gives equal time to opinions that many might find objectionable today. For instance, although Shakespeare makes some very eloquent arguments for chastity in The Sonnets (calling promiscuity “an expense of spirit in a waste of shame”) he also frequently tried his hand at Elizabethan pornography (Benedick to Beatrice: “I will live in thy heart, die in thy lap, and be buried in thy eyes.”) Finally — to hit on a subject that has traditionally been banned at dinner to keep the family peace — Shakespeare’s work is equally, if not more, pagan, than it is Christian. The plays are populated as much by faeries, witches, elves, sorcerers and sprites as by The Holy Trinity.

Students will find in Shakespeare absolutely no moral compass. They will be required (and this is truly the toughest slog) to think for themselves.

And if we cancel Shakespeare, we cancel that.

Sky Gilbert is a Canadian writer, actor, educator and drag performer. He teaches creative writing and theatre studies at Guelph University. Sky’s accessible analysis of Shakespeare’s rhetoric "Shakespeare Beyond Science: When Poetry Was the World” was published by Guernica last year, and his new novel “I, Gloria Grahame’ will be released by Dundurn Press in the fall.

The Line is Canada’s last, best hope for irreverent commentary. We reject bullshit. We love lively writing. Please consider supporting us by subscribing. Follow us on Twitter @the_lineca. Fight with us on Facebook. Pitch us something: lineeditor@protonmail.com

For my own teaching practice, i look at the limited time we have with kids - four classes in English Lit, usually - and ask: what works will inspire kids to Ever Read Again after we stop being able to compel them? Four opportunities to encourage love of the written word. We faced the same problem in music classes - an opportunity in the 70s to inspire musicians, and an audience of kids absolutely in love with music - and teachers had us playing in an orchestra, music irrelevant to us, and it sucked the life out of the art. We have finite opportunities, and to indulge our aspirations to fanciness is wasteful. Shakespeare is glorious - teach so readers one day seek out and fall in love with Shakespeare.

I love Shakespeare. But the language in the plays is simply too difficult for high school students. "Grade Saver" companies online are making a fortune.