Mitch Heimpel: So long, Business Liberals.

Who are the Liberals' voters today? What's their coalition? And do any of them think about monetary policy?

By: Mitch Heimpel

As Bill Morneau approached the podium at the C.D. Howe institute last Wednesday, he could only have guessed that he was about to deliver a eulogy.

In part, because the electorate in the province of Ontario wouldn’t declare the body dead until slightly after 9:15 the next night.

Also because, Morneau, perhaps unbeknownst to himself, is among the last of his breed.

Business Liberals, Corporate Liberals, Boardroom Liberals, Blue Liberals —whatever you want to call them, they were long a major source of power and influence inside of the Liberal Party, but are now on the outs. Had Morneau been warned of the wreckage that was about to befall the Ontario Liberal Party that night, it’s interesting to think of how much further he would have, or could have, gone about his time as a federal Liberal finance minister.

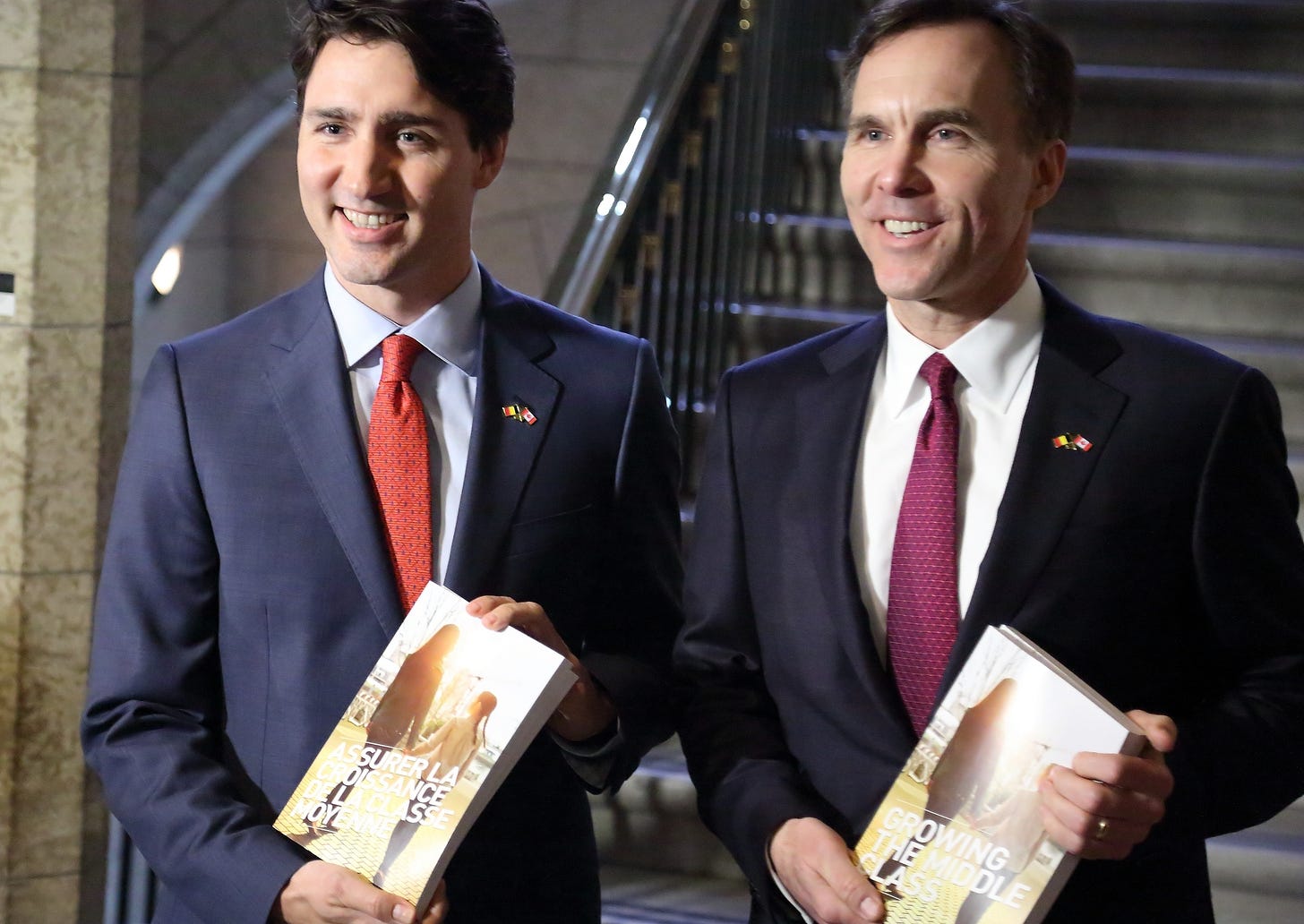

To outsiders, Morneau never looked totally at home on Justin Trudeau’s benches. To hear Morneau tell it during last week’s address to the C.D. Howe institute, he never really was. Morneau focused his speech on Canada’s lagging economic growth and the danger this poses to our standard of living and way of life, and noted that Canada compares unfavourably to other similar countries, who are getting richer while we tread water.

“I struggled to get our government to focus on the need for sustained economic growth because it was constantly crowded out by other things that seemed more politically urgent … Even if they weren’t truly as important,” Morneau said.

From the standpoint of economics, the numbers back Morneau’s argument. But what about the politics? Morneau’s words paint the picture of a man viewed by his fellow Liberals as a relic. A product of a by-gone era, that they needed to maintain the brand and the bond markets — but which has little political value to the party in the long term. To hear Morneau tell it, he was a man alone. That’s just his version, of course, and he certainly has a bias. But the fact that he felt moved to give the speech, sharply critical of his former peers as it was, and the possibility that it may be true, tells us how different today’s federal Liberal Party has become from what even senior Liberals of very recent history would find familiar.

Meanwhile, on the provincial scene, Steven Del Duca comes from the same tradition as Morneau, if not with the same pedigree. Morneau is the boardroom, the Granite Club and the Rosedale set. Del Duca is the partisan fighter. To read Steven Del Duca’s resume is to see decades of political experience in building and maintaining a well-tapered Liberal tradition that rose to prominence in the 1980s with John Turner and David Peterson and was inherited first by Paul Martin and Dalton McGuinty.

That tradition was that of an urban, upwardly mobile, business-friendly party that placed itself cautiously on the socially progressive side of culture war issues. It was Peterson, after all, who first pledged to liberalize alcohol sales in Ontario and ended the provincial ban on Sunday shopping.

This largely kept the Ontario Liberals in power in recent decades. It certainly had no trouble being popular in Ottawa in the 1990s, either.

But that’s not what the Liberal party, federally or in Ontario, is anymore. Or, at least it’s not who Liberal voters and activists are anymore.

Del Duca’s result on Thursday night seems to suggest that the little value that Morneau’s cabinet colleagues placed on his policy priorities is based on a hard political reality. The Business Liberal is neither necessary nor sufficient for the Liberals to win elections. They are pursuing other voters with different policies.

I could feel this shifting reality when I watched the convention that elected Del Duca leader. From his time as Joe Volpe’s riding president, and an aide to former finance minister Greg Sorbara, Del Duca had been a Liberal fixture for decades. No one could doubt his partisan credentials. No one could doubt the work that he’d put into making brand Liberal a force in Ontario.

Yet the mood at that convention was that of a kind of uneasy compromise. A party base that adored socially progressive Kathleen Wynne, despite her historic loss, was going back to Dalton McGuinty's tradition on the promise that it was necessary to win over enough voters to form government.

The subtext was obvious to observers: you won't love Steven Del Duca, but you love being in power, so here's the deal. Now the Liberals lack even that.

In one of the last polls before the election, Del Duca was the preferred premier of only 39 per cent of Ontario Liberal voters, coming only nine points ahead of Andrea Horwath among his own partisans. Horwath, by contrast, had a 67-point lead on Del Duca among NDP partisans. Del Duca’s personal popularity regularly trailed the Liberal brand by anywhere from 10-15 points.

There is a theory about elections. It's a belief that "the middle of the road is where you get run over." The thinking is that you can't win without exciting your core voters. Getting your own tribe out to vote is more important than persuading new voters. Bill Morneau’s odes to productivity and economic growth don’t excite the Liberal base. Steven Del Duca’s transactional stakeholder politics of “buck-a-ride” and optional Grade 13, didn’t either.

Whatever the Liberal party is now, especially in Ontario, it's not the party that Steven Del Duca came up in. It more closely resembles Kathleen Wynne's party, or Justin Trudeau's. These are still urban parties, but more concerned with the culture war than Dalton McGuinty (who famously backtracked on sex education reform), or Paul Martin (who had very mixed feelings on same-sex marriage). It is less concerned with upward mobility than it is with wealth redistribution. It doesn’t think much about economics or fiscal policy.

Parties change all the time. Voting coalitions change. None of this is necessarily bad. It’s not the early 1980s, and it makes sense that the Liberals would have to change to reflect a new and different age. But these shifts can be messy and confusing. The federal Liberals won most of the close Ontario races in 2021, and the election. Del Duca lost those races, the election and his job. It’s not clear yet which of those was the fluke and which was the future.

The interesting question for the Liberals, federally, though, is that they have a host of business-friendly types lining up to take over from Justin Trudeau, from François-Philippe Champagne to Anita Anand. Their policy reality is what Bill Morneau uttered Wednesday morning: they’d likely agree that Canada needs to focus more on growing its economy for everyone, so that we can pay for programs at home and compete aggressively in a tough world.

But their political reality is Steven Del Duca’s — is that what gets Canadians excited? Or is the path to power taking bold stands on the right wedge issues and maximizing your vote efficiency in critical ridings while not thinking about economics much at all?

So, for Liberals, in Ontario and federally, here are the key questions. Who are their voters? What’s their coalition? What will excite the party? And how are they going to get out of the middle of the road?

Mitch Heimpel has served Conservative cabinet ministers and party leaders at the provincial and federal levels, and is currently the director of campaigns and government relations at Enterprise Canada.

The Line is Canada’s last, best hope for irreverent commentary. We reject bullshit. We love lively writing. Please consider supporting us by subscribing. Follow us on Twitter @the_lineca. Fight with us on Facebook. Pitch us something: lineeditor@protonmail.com

Good article. I am starting to suspect that a large number, possibly the majority of Canadian's have no political party that truly represents them. Unfortunately I find myself in that number, and really wonder what I will do next election.

I am one of those voters without a home. I am in that 'Blue Liberal/Red Tory' band. I am very concerned with lagging productivity as that has such a huge downstream impact on all public policy; as the economy fails to meaningfully grow, we're left arguing about how to redistribute (or not) the same size pie.

While parties vie for 'engaged' voters by promising to fix issues that they really have limited ability to deliver on, their constituencies are getting smaller and more partisan. Meanwhile, they seem to be actively encouraging people like me to get disengaged.

I suspect -- and hope -- that some smart party (even if it's a new party) will see that gap and fill it. I don't know a lot of actual partisans beyond the digital realm; I suspect there are a lot of fairly disengaged, discouraged people who might vote for a party that stops yelling, promises things they can actually deliver (then does) and generally focused on "peace, order and good government". But, maybe I'm dreaming.

FWIW, though, I do think that Del Duca was an uninspiring candidate and his platform seemed full of the kind of gimmicks that made it hard for voters like me to take him seriously.